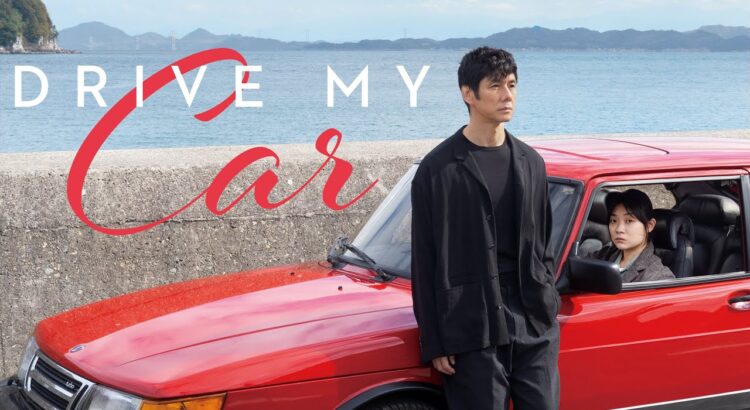

Drive My Car is a Japanese film based on a short story of the same name from Men Without Women, a collection of short stories by Haruki Murakami. The film follows theater actor Yūsuke Kafuku as he directs a production of Uncle Vanya by Chekhov two years after the death of his wife.

I have had some exposure to Murakami’s work, having previously seen the film Burning, which is based on another of Murakami’s short stories, and having read part of his novel The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. I really enjoyed Burning, how slow and meandering it felt while building and maintaining a quiet sense of tension and mystery. I found out Burning was based on a Murakami story after I realized Drive My Car reminded me of it, in terms of pacing but also the way in which the female characters were perhaps quite evidently written by a man. I have only read part of The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle because I thought three manic pixie dream girls was maybe too many, but after watching the entirety of Drive My Car, I do want to return to the novel and see what Murakami has to say.

It turns out that Murakami’s works are worth sticking out to the end – especially Drive My Car. Once we get past Murakami’s formulaic introductions of a lone, troubled male protagonist, and the sultry and promiscuous women in his life, we uncover a central theme of grief. Though this overall message of the film is not particularly revolutionary or unheard of, it is the way in which it is expressed that makes it worth noting. I ended up reading the short story after watching the film, and I really liked how writer-director Ryusuku Hamaguchi emulated the almost nonchalant delivery of the short story’s message. Though the film has more dramatic moments, it’s the slow buildup to get to these moments that feels faithful to the source material. The film feels like a natural development and continuation of Murakami’s original story.

Furthermore, the film reminds us that when our words fail us, we can find and express ourselves through art. For Kafuku’s wife it is through her screenplays, and for Kafuku and his scene partners, it is through performance. And the film also reminds us that we can find solace in knowing we are not alone in our grief, even if it is through a temporary companionship. Drive My Car doesn’t move you to tears, but I like to think it doesn’t need to.