Return to Seoul is a film that is resonant in its essential question of “how does one consolidate the roots of one’s own identity when they are foreign to oneself?” The movie follows the 25 y/o Freddie as she navigates the country of her birth and its foreign cultures and people. Originally traveling to Korea on a whim with her friend Tena, she decides to pay a visit to the Hammond Adoption Agency that facilitated her adoption. The creation of these international adoption agencies began from the large amount of Korean orphans resulting from the aftermath of the Korean War in the 1950’s. From this, she is contacted by her birth father, who has been separated from Freddy’s birth mother, and she makes the decision to go see him with Tena. However, her trip there is mixed with reluctance, the ambivalence is painted on her face to the point that you can feel her stomach churning. Her worries are justified when she comes up feeling even more disconnected to the family that revels in her return. While her father wants Freddie to stay in Korea, she cannot as she is a French woman with a home, friends, and family back in France. He cannot accept this, however, leaving her discomfort to culminate in an encounter where he follows her to a bar, and she rejects his drunken fatherly embrace, screaming “Don’t touch me!”

Freddie markedly does not fit in with the culture in Korea, and her experiences in her first trip to Korea certainly show this aspect of her the most. She is explicit in her defiance of cultural norms and etiquette, making sure that others know that she is a French woman, not Korean. To this effect, Tena’s translations fail to express the harshness of her words, and the language barrier between her and the Koreans in the movie further complicate her disconnect from the culture. Additionally, Freddie is simply an interesting character, for she swaps between lifestyles, partners, and friends throughout the entirety of the three-part movie. She is brazen, indulging herself in music, soju, and hookups.

One final thing I was intrigued about was the use of extended scenes of music with the stages of Freddie’s life in mind. In any capacity, the music plays an integral role in representing the different phases of her life through all of the different time-skips. It helps to describe how her freedom and independence manifests throughout different genres, characterizing Freddie through her different stages of life: as a young woman moving through adulthood. It’s an intensely resonant narrative device that creates beautiful juxtaposition with her coming of age.

The film screening of Return to Seoul was shown as a part of the Korean Cinema NOW: Diaspora Edition event. These movie showings are presented by the NAM Center on Saturdays in the Michigan Theatre throughout the Winter 2024 semester. If you’re interested in Korean cinema—especially as they relate to the Korean diaspora or diasporic identities in general—then there are still many more films being put on, and they all have free admission with catering from Miss Kim herself (I have to say that the food is really nummy! (˵ •̀ ᴗ – ˵ ) ✧). So, don’t hesitate to indulge in a fun Saturday outing these movie are worth it!

Runtime: 1 hr 59 min

Rated R

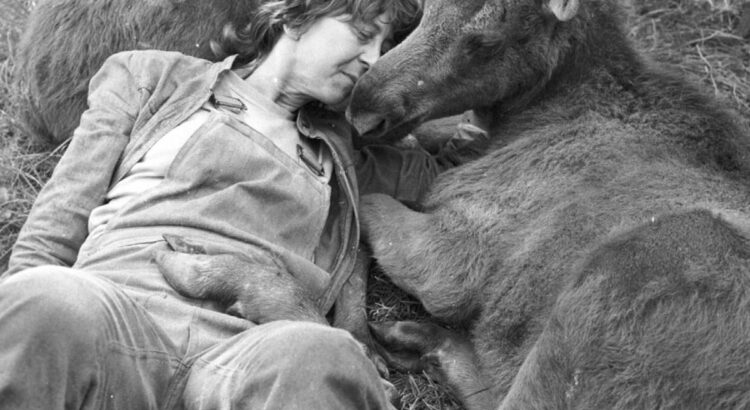

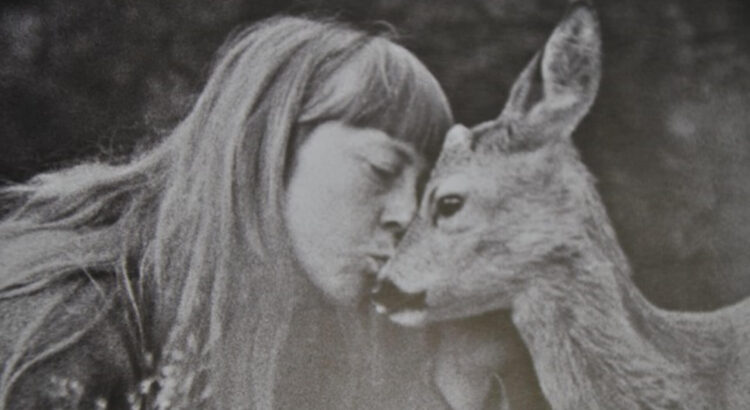

Screenshot of the movie taken from the npr Article: “‘Return to Seoul’ is About Reinvention, not Resolution”