I used to pride myself in my cold-heartedness while watching emotional movies. While others wept over Les Mis I did not shed a single tear, and in this astonished both my peers and myself.

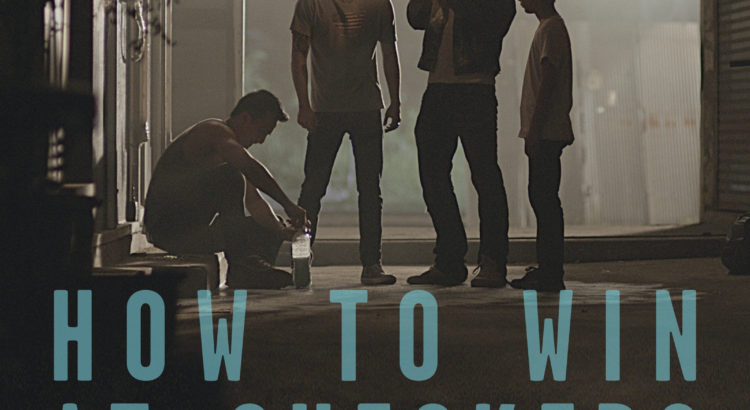

These days, this old pride is abandoned totally. Now I use how much I cry as a measure of how good the movie is. So, by the Sorrow Scale, How To Win At Checkers (Every Time) was fabulous. The purity of the brothers’ relationship is tragic in the face of government corruption and rapidly-moving sadnesses. Despite how inevitable the turning of events were, I’d still catch myself hoping along with the characters.

The bond between Oat and Ek is realistic–not too sitcom-family well-behaved, but teasing and jeering and ultimately loving. It informs the questionable decisions Ek can make concerning his kid brother, like letting him come to the club with him. They both need another, less alien parental figure than their aunt, after the death of their parents, especially Oat. Ek is not a perfect father figure, which is quite the accurate representation, as he is so young himself, and could use someone guiding him as well.

Small things held significance in this film, working with subtlety that enhanced its themes of injustice, which is similarly slyly hidden to all those not looking for it. Take the draft lottery scene; while the crowd was singing the national anthem, Jai and Junior are one of the few pointedly not participating. It’s unclear whether they do so as they contemplate their part in the bribing, or the fact that the government accepts bribes to escape the draft at all. Perhaps they feel less connected to their country as a result. But hasn’t Ek earned the right to antipatriotism? He is stuck in the nerve-frying situation of facing possible death and leaving his young brother behind. Still he sings the song of the country that has none of his interests in mind.

The color palettes are similarly subtle, simple combinations of muted earth and jewel tones that drag at the feeling of bleakness the later parts of the movie hold. Even the Cafe Lovely has a limited scheme, a little monochromatic neon against dark grays and browns in its rooms. Upstairs, that sinister place, is even flatter, an apartment building hallway of beige. In such environments I can feel the barrenness of the situation, in contrast with the joyous times of childhood. We see here that evil works in a lurking way, striking without ceremony.

And although I have mostly positive views on Checkers, there were several instances of triteness that shocked me. Worst of all was the very ending, where an adult Oat rides out into the sunset, which turns to white as he gets to the horizon. I wanted to gag at this foolishly, blindly at-peace, going into the light ending. To me, it ruined much of the unique qualities the movie did contain. Instead of Ek’s painfully unceremonious killing, I was thinking about how much this reminded me of The Ghost Whisperer. At that point, I seriously considered labeling this a feel-good movie instead of the deeper drama it tries to be. I wondered how it could be nominated for an Oscar when they couldn’t think of a less superficial way of ending it.

But what matters most is one’s overall feeling walking out of the movie. At that time I was still crying, so by my measure of choice, it was still a powerful film.

This is director Josh Kim’s first full length film. He has also made several other short films to check out: Draft Day, The Postcard, and The Police Box. This was the last Thai Movie Night of the semester, but they will be starting up again at the beginning of the year.