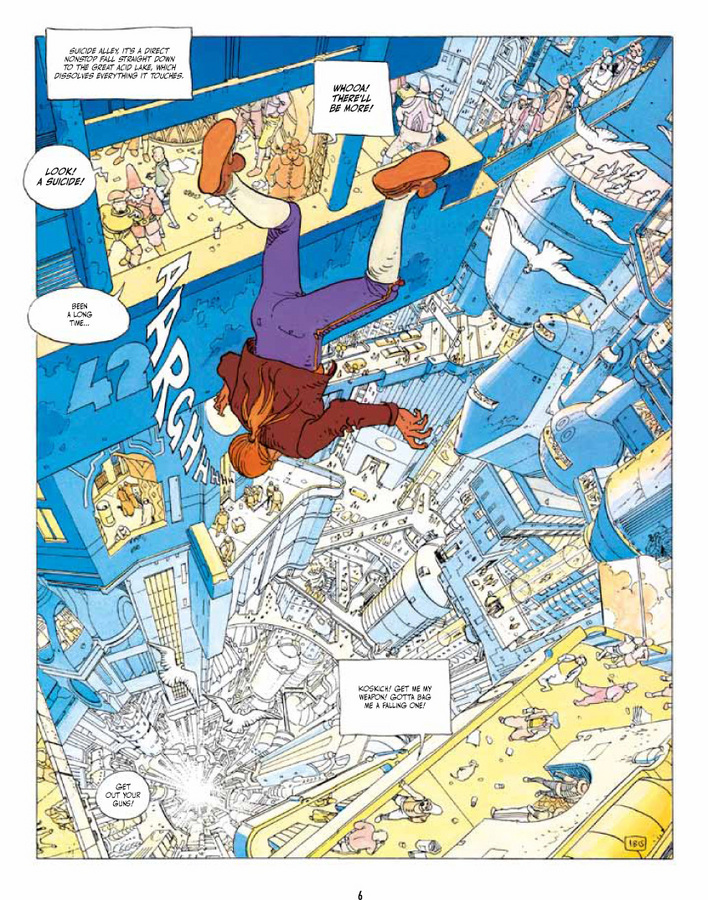

How do you start a story that takes place in a world as strange as the one found in The Incal? Answer: you toss your protagonist down Suicide Alley; a locale m

ore vertical than horizontal; a place where your face meets an acid lake, not concrete. Of course John Difool, the class “R” Licensed Private Investigator, is fully aware of what kind of place Suicide Alley is. But we don’t.

Any story that delves into a world via some tunnel, vertical, horizontal, diagonal, what have you, harks immediate comparison to Carroll’s famed work. Unlike Alice however, John never lands, but is caught by his pursuers just before plunging into an acid bath; his fall is not made alone; there are spectators, watching, some eventually joining; the plunge into this world is incomplete yet complete, and more importantly, it is oddly shared by the numerous fictional characters surrounding the rather interruptive action. But this interruption, what others perceive to be just another namesake suicide of the Alley, is as mundane as the narration accompanying the images of falling bodies, white birds, and the tubular urban hub encompassing the endangered Difool. “His fatal plunge down Suicide Alley triggers the usual wave of suicides,” the narrator notes. It’s all expected.

For once we don’t need to journey into Wonderland – the rabbit hole already surrounds us. It very much feels like the anti-rabbit hole, a jab, a jocular implementation of audience expectancy so keenly reflected by the near death and subsequent sparing endured by Difool. If anything, that model only repeats itself throughout the comic, as Jodorowsky and Moebius let us fall and get caught in false-safety-nets as if the fall is eternal. We are treated like ragdolls like Difool, tossed down the Alley and not spared the acid pool unlike the suicides plunging after Difool. Reading The Incal, you are taken for a ride.

For once we don’t need to journey into Wonderland – the rabbit hole already surrounds us. It very much feels like the anti-rabbit hole, a jab, a jocular implementation of audience expectancy so keenly reflected by the near death and subsequent sparing endured by Difool. If anything, that model only repeats itself throughout the comic, as Jodorowsky and Moebius let us fall and get caught in false-safety-nets as if the fall is eternal. We are treated like ragdolls like Difool, tossed down the Alley and not spared the acid pool unlike the suicides plunging after Difool. Reading The Incal, you are taken for a ride.

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!