Commissioned by the Coventry Cathedral Festival for the 1962 re-consecration of the Coventry Cathedral, which was destroyed by Nazi bombings during World War II, Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem is a truly haunting piece. Undoubtedly his masterpiece, it combines the Latin liturgy of the Mass for the Dead, sung by soprano and the chorus, and children’s chorus, with the English language war poems of Wilfred Owen, sung by tenor and baritone. The piece was performed this past Saturday by the Ann Arbor Symphony, UMS Choral Union, and Ann Arbor Youth Choral, under the baton of Mr. Scott Hanoian.

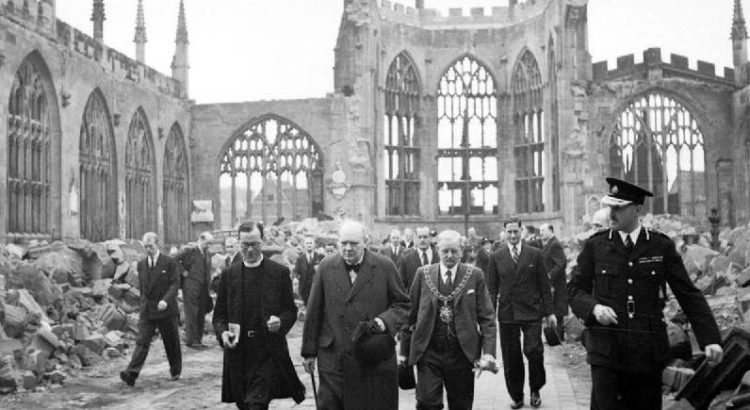

The work is chilling from the beginning, and it opens with the tolling of chimes and the chorus quietly chanting “Requiem.” The music is simultaneously very much in the 20th-century style, while also clearly drawing from and referencing much earlier works, and it similarly blends modern poetry with centuries-old liturgy. In some ways, this parallels the old and new cathedrals – the old cathedral was built in the 14th and 15th centuries, and the decision to rebuild it was made the morning after its destruction at the hands of the Luftwaffe.

Shortly after the destruction, the cathedral stonemason, Jock Forbes, noticed that two of the charred medieval roof timbers had fallen in the shape of a cross. He set them up in the ruins where they were later placed on an altar of rubble with the moving words ‘Father Forgive’ inscribed on the Sanctuary wall. Another cross was fashioned from three medieval nails by local priest, the Revd Arthur Wales. The Cross of Nails has become the symbol of Coventry’s ministry of reconciliation.

Her Majesty the Queen laid the foundation stone on 23 March 1956 and the building was consecrated on 25 May 1962, in her presence. The ruins remain hallowed ground and together the two create one living Cathedral.

Source: http://www.coventrycathedral.org.uk/wpsite/our-history/

The Ann Arbor Youth Chorale, which sang the part of the children’s chorus, was seated in the balcony, which was a decision that I thought added to the drama of the piece. The Youth Chorale only sings four times in entire eighty-minute work, and because I couldn’t see them from my seat, their entrances were (almost, if it were not for the translations in the program) unexpected. Furthermore, their position above and away from the rest of the performers and the audience gave a feeling of otherworldliness and innocence.

Also strategically positioned on stage was Ms. Tatiana Pavlovskaya, soprano. Rather than being at the front of the stage with Mr. Anthony Dean Griffey, tenor, and Mr. Stephen Powell, baritone, Ms. Pavlovskaya stood in the midst of the orchestra. I think that this probably enhanced the blend between her exquisite voice and the orchestra, and it also was a fascinating artistic decision – in her black gown, she faded into the background of the orchestra, rather than stand out as a soloist.

I did appreciate that the words of all parts, as well as the translations of the Latin liturgy, were included in the program so that the audience could follow along for the duration of the work. Simple efforts such as this greatly increase the piece’s accessibility, since most audience members are not fluent in Latin, and sometimes even the words of English pieces are sung too quickly to digest.

At the conclusion of Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem, the audience sat in weighted silence for a lengthy period, which I think is a testament to the piece’s lasting impact.