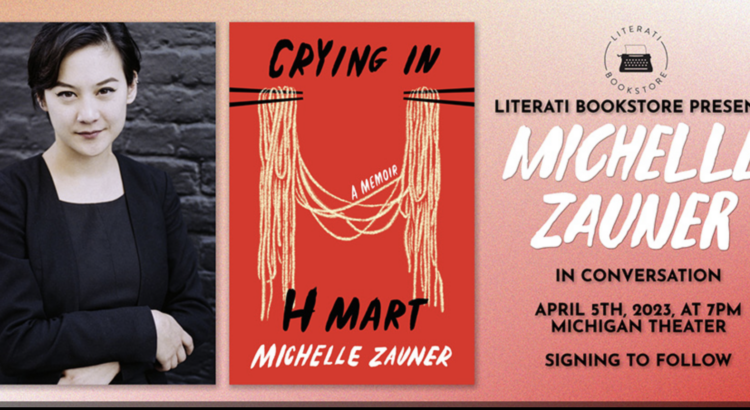

Michelle Zauner’s last stop for her book tour was yesterday night at the Michigan Theater. I arrived an hour early for the event, but the line was already so long that I couldn’t get a front-row seat… understandable because the tickets sold out within a week.

Michelle was interviewed by one of the University’s professors, Kiley Reid, and they touched on a variety of topics such as how the cover of Crying in H Mart was designed, how her book came to be published, what kind of scenes she wishes she could’ve included, and many more. I can’t capture all the details of their conversation, but here’s a quick summary of how Crying in H Mart came to be:

After her mother died, she found a ‘real’ job in New York advertising wallpapers. During that time Michelle found herself deeply engrossed in cooking Korean food. This experience inspired her to write an essay that she submitted to thousands of agencies. It was only after a year of rejections that an agent reached out to her, which was also around the same time her band, Japanese Breakfast, began to grow popular.

She prioritized her music career, but as she traveled around the world she strived to write 1,000 words a day during plane rides or as she waited backstage. Most of the book was written during her world tour for Japanese Breakfast. After reading her first draft, though, Michelle realized that her writing was so full of anger: anger at every person and anger at all her experiences, which wasn’t the kind of memoir Michelle wanted to write. Once she reached her last destination in South Korea however, the place where her mother grew up, she learned that there was more to write about outside her grief, and after continuously cutting down, editing, and revising her work, she had her final product: the first chapter titled Crying in H Mart.

After her interview with Kiley, there was also a Q&A session. Many people asked Michelle for advice on how to connect with their culture and progress their careers as a writer. She advised people to continuously interact with aspects of their heritage, whether it be learning history, taking language classes, or cooking food until it becomes a part of them. She also emphasized that to be a good writer, you have to write a lot of shit.

Overall, it was a super inspirational experience. It was also the first time I met an author, and Michelle was so humorous and down to earth. I initially thought the event would be a serious discussion due to the topic of the memoir, but it turned out to have a light-hearted atmosphere. There will also be a movie adaptation of the book!

I can’t wait to see what Michelle has planned for us in the future.