A little bit haunting, a whole lot confusing, maybe threatening. These pictures gave me the feeling of a kid from the Peanuts gang; kept from some secret like the unintelligible monotone of the adults’ voices. It was something special to be let in at all, but the opacity of the images’ meaning both disturbed and delighted me. The lighting–heavy flash going off in naturally-lit or dark indoor environments–put me back in time a bit. The images were reminiscent of the 1990s with their coldly fashionable earth tones: grays, browns, tans, beige.

The ones with captions seemed like they could have had a clearer intent. We have location and the number of inmates, but that’s about it in terms of context. I needed more from the literature if the artists wanted to include it at all. Mere numbers fail us in giving meaning to most things; I need more description of living conditions, maybe a hint at artifacts of the imprisoned life, the possessions they leave behind at the gate, art made by inmates, some little picture of influence they have on their surroundings and the lives of others.

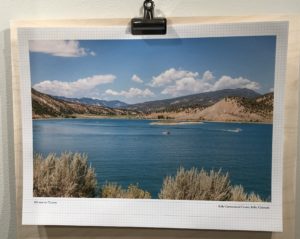

It was interesting that all the photos surrounding correctional facilities were taken from the outside (necessitated by strict no-photo policies, undoubtedly), often not including the buildings at all, but focusing on the surrounding landscape. Most of the others–bail bond shops, police gun shows–were taken from inside. Are we meant to feel a kinship with the law, or just deny ourselves a false connection with the incarcerated? To be outside is both a privilege and a curse: it grants us our continuing freedom while suffocating the possibility of real understanding.

Using such majestic landscapes was a unique artistic choice for me. Many incorporated deeply vibrant colors in the sky and greenery; there was a lot of sunshine and a calming, natural glow to them. Several could have been featured on a ritzy resort’s website. They’ve taken away the images of concrete blocks and barbed wire I would normally associate with prison and replaced them with a richer depiction. “There is beauty here!” they shout. There is no longer the usual isolation of a building from the land on which it sits; instead it becomes a part of something more complete. Exactly what that is, I’m not quite sure. There is no reference to the incarcerated housed within the walls we cannot see from our vantage point, save for a mention of how many there are. Personalization is negligible, nothing more than the city and state printed below the picture. If we are not meant to focus our thought on the prisoners, what else are we supposed to consider? Or is their absence itself the point? Thus the argument is unclear. I will definitely be going to the artist talks coming up, and I suggest you all do the same after perusing the gallery. Steph Foster will give an artist talk on Friday March 27, at 4:45 PM, and Ashley Hunt will give an artist talk on Tuesday March 31, at 4:30 PM.