The ampersand is one of the most flexible symbols in our alphabet, allowing an impressive range of interpretation and aesthetic freedom. But how can the appearance of this swirly bit of confectionery be related to its function but in an arbitrary way? What’s to stop someone from drawing an elephant, for instance, and declaring it to mean “and� There is, as it turns out, a surprisingly logical history. Concisely put, the ampersand is literally the physical representation of the Latin et (et cetera, et al.)— “and.†In some typefaces, this is still visible.

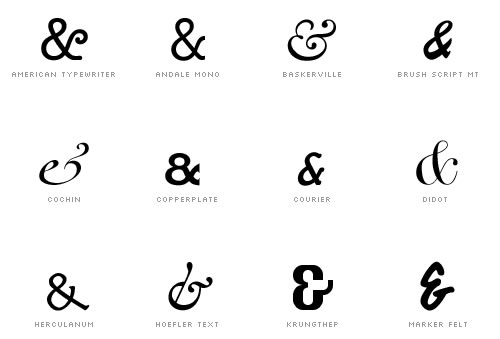

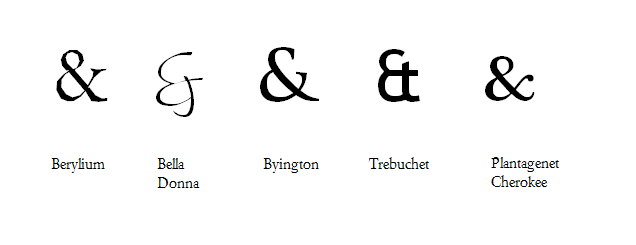

In the second and fourth examples, the letters e and t are distinguishable. The other fonts are, essentially, variations upon variations of the same basic design. What appears to be a single symbol is in fact a ligature, which is something consisted of two joined graphemes— basic written units (letters, in the case of English). In turn, the ampersand as a whole is categorized a logograph, a symbol that represents an entire word.

In the second and fourth examples, the letters e and t are distinguishable. The other fonts are, essentially, variations upon variations of the same basic design. What appears to be a single symbol is in fact a ligature, which is something consisted of two joined graphemes— basic written units (letters, in the case of English). In turn, the ampersand as a whole is categorized a logograph, a symbol that represents an entire word.

And the word itself, “ampersand,†comes from “and per se and,†from when “it was common practice to add at the end of the alphabet the “&” sign as if it were the 27th letter†[wikipedia]. After z would come “and†by itself, or per se and— hence, “and per se and.â€

Using the ampersand in writing is usually an informal and dashed affair, such as one might do when taking notes in shorthand. A quick little e with a line cross it, perhaps. In formal writing it is little used, except in titles and names. Yet this symbol can be a oddslot template that allows a great deal of artistic license. The construction of the ampersand, like any other letter of the Latin alphabet, must be recognizable, but outside of that, can manifest itself in any fashion. It might have fewer constraints than any of the twenty-six letters, even, because its appearance does not have to be legible, immediately recognizable, able to be processed in conjunction with other symbols. And in the end, really, the ampersand is easily one of the characters with the most creative potential.