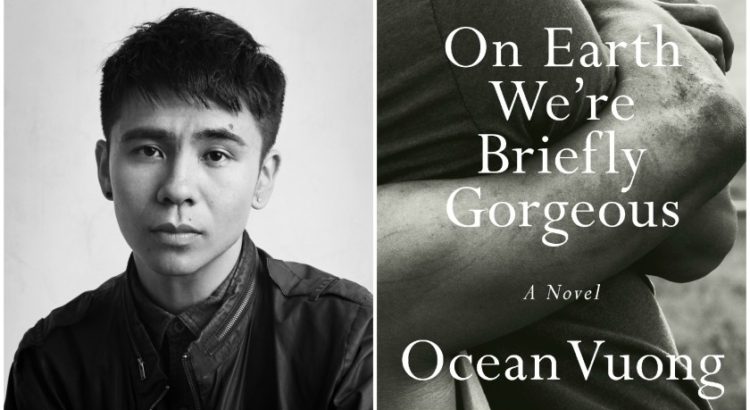

Even the author’s name, Ocean Vuong, is quite beautiful. I came to this autofictional novel with high hopes in mind, going off all of the hype that Vuong’s first prose debut was generating. Named a best book of the year by many, I was a bit skeptical of the power of this book at first, because his previous chapbooks of poetry weren’t my style. Nonetheless, I checked out the black-and-white-covered novel and set forth.

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous took me two days to finish. I was amazed, impressed, shaken a little. Knowing that Vuong is also a queer Vietnamese person, I strongly identified with his intense emotional narratives. The novel blurs the line between personal lived expreience and literary fiction, but seeing a Vietnamese immigrant gain immense praise and popularity in the literary world gives me a sense of inspiration and pride as well.

Written in the form of letters from an adult son to his illiterate single mother, Little Dog reminisces on his current life and turbulent childhood growing up as a first generation American in the back of a nail salon where his mother works. He writes of his well-meaning grandmother with schizophrenia, his first sexual experience with a farm boy, and the trauma associated with growing up in a town rife with addiction.

Most striking to me was Little Dog’s complicated relationship with his mother. Abusive at times and loving at others, the author gracefully explores how people experience unconditional love and healing. The author writes at one point, “Perhaps to lay hands on your child is to prepare him for war.” Vuong’s prose is so fluent and eloquent, yet parts of the book were so emotionally violent at times, I was left in awe of his words. Each sentence is equally beautiful and striking.

To sum it up, I absolutely loved On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous.