Hey again! This is a little less slice of life but I’ve been getting into The Pretenders lately and I wanted to write a little comic about them. Also please listen to “Back on the Chain Gang”, it’s a jam and a half!!!

Hey again! This is a little less slice of life but I’ve been getting into The Pretenders lately and I wanted to write a little comic about them. Also please listen to “Back on the Chain Gang”, it’s a jam and a half!!!

Hey! This is Marge. I’ll be posting comics here every Saturday afternoon for y’all.

I love comics, especially the literary variety known as graphic novels. I was ecstatic when I heard that the art school was going to host a talk by none other than Art Spiegelman, the Pulitzer Prize-winning comics artist, as part of the Stamps Distinguished Speaker Series. He solidified the genre of the graphic novel with his work “Maus”, a gripping account of his father’s survival during the Holocaust with Jews depicted as mice and Nazis depicted as cats.

Spiegelman’s presentation was titled “Comics is the Yiddish of Art”, the thesis that drove his roughly 90-minute talk. He described his inspiration from the greats, starting with Superman creator Jack Kirby, a Jewish American like himself. As the talk went on, Spiegelman argued how comics were not just a home for Jewish American artists, but for outsiders in general. He compared the localized nature of Yiddish with the fluid grammar of comics as a visual medium. The unusual comparison felt justified and of personal interest to Spiegelman.

But his talk fell flat when he addressed the sexism and racism that has fueled comics for decades. After discussing how comics were condemned by authorities and even burned due to their provacotive content, he showed an example of how comics (by men) hid images of women’s groins and breasts in the background. This was followed by an anecdote of how he loved to draw women’s breasts and groins in junior high that he would then morph into the faces of dogs to avoid repercussion. This got a laugh out of the audience, but I was unsettled. The art professor who had introduced Spiegelman to the audience, the incredibly talented Phoebe Gloeckner of “Diary of a Teenage Girl” fame, had said she was interested in hearing the connection between Jewish identity and comics as she had always felt as an outsider due to being a woman cartoonist. The way Spiegelman showed comics’ history of objectifying women made it feel inevitable, as “boys will be boys”. I wondered if male cartoonists ever considered how their crass attitude to portraying women alienated their peers like Gloeckner.

His discussion on racism had a similar problem of perpetuating the stereotypes that keep diverse artists out of comics. While calling out the racist caricatures that became a foundation for comics, he showed how he made a cover full of racist caricatures for “Harper’s Bazaar” after Danish newspapers went under fire for depicting the prophet Muhammad, which is prohibited by Islam.

I was disappointed. Spiegelman spoke of his frustration with identity politics and his disillusionment in becoming a spokesperson of sorts for the Jewish community when he considers himself an artist first and foremost, leading me to believe he is against having art shoehorned due to the identity of its author. And yet he was continuing comics’ tradition of not being sensitive to the disrespect faced by people with marginalized identities in the art world.

I am cognizant that Spiegelman used coarse language with all social identities depicted in the art he included in his talk. He shared stories of being considered anti-Semitic for not portraying Jews or the Holocaust in a traditional way, a discussion best left to his own community. But as a Latina who is always striving to find representation in the media, I was not amused by his lack of interest in making comics a more inclusive medium. After his talk I was inspired to send an op-ed comic of my own to the Michigan Daily, and I finish this article with my head held high and hopeful of the future of diverse artists.

“I’m at the top of my game. Leave saving the world to the men? I don’t think so,” says Elastigirl, in the 2004 Pixar movie, “The Incredibles.” As more and more women come onto the superhero scene, the conflicts become less about right and wrong, and transform into a war of the sexes. So far, in my English 418 class about Graphic Narratives, we’ve seen very few women populate our comics. When we do, the women are mostly depicted only as victims. This coming week, we begin to see Misty Knight in “Power Man” hold her own … most of the time. But even Misty is saved by Iron Fist in “Freedom” when she, as a trained cop, can obviously fight for herself. Iron Fist shifts the power scale heavily to the side of the male hero: man’s judgment is seen to trump all other opinions.

So what happens when females try to be in charge? Are they successful? How are they depicted? What do the female characters tell us about the men who try to overpower them?

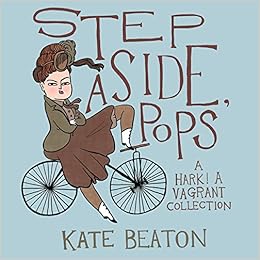

Comics writer and artist, Kate Beaton, focuses much on parodying historical, literary, and pop-culture figures, all while offering up perceptive critical analysis of social politics. Beaton tends to turn toward the female perspectives, and often gives a voice, albeit one that is sarcastic and snarky, and attention to those women who often are the background noise. Beaton’s also strolled into the world of superheroes a few times, with Wonder Woman, Aquaman, and even Spiderman (dubbed by Beaton as a more specific “Brown-Recluse Man”). The value of superhero parody is that she can explore the heroic characters that everyone wants to be like, whom everyone wants to be victorious, yet no one knows anything about as a “real person” – you know, the real person who goes to the bathroom and gets drunk on Thursdays and picks their nose when they think no one is looking.

In her new book, Step Aside Pops, Beaton pays homage to Superman with the comic, “Lois Lane, Reporter.” The entire story is made up of 6 unrelated 3-panel comics, all depicting the various ways that Superman screws things up for Lois and generally gets on her nerves. Kate Beaton says, in the footnote of Step Aside Pops (pg. 16), “Don’t give me those comics where Lois is a wet blanket who can’t figure out the man beside her is Superman. If Lois isn’t kicking ass, taking names, and winning ten Pulitzer Prizes an issue, I don’t even want to hear about it.”

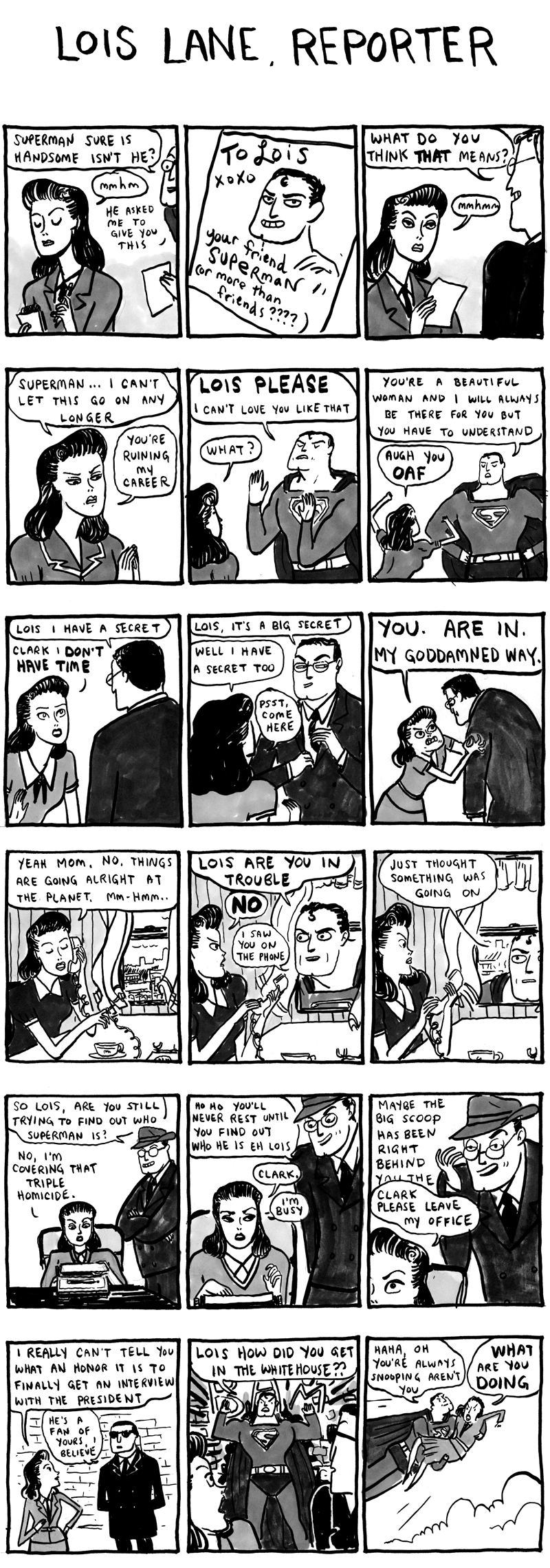

Beaton certainly paints Superman/Clark Kent in a different light than he was in the original Siegel and Shuster comics. Instead of the weak and cowardly Clark Kent we saw in his 1938 debut, “Champion of the Oppressed,” we see a persistently bothersome coworker whose double identity is obvious to Lois based on his obscure behavior, and she could care less about him if he was Superman or Cristiano Ronaldo. Lois is busy, driven, and is trying to save the world in her own way- by reporting about it. But, does Kate Beaton truly represent Lois as the no-crap-taking girl she wishes Lois could be?

(via: http://www.harkavagrant.com/index.php?id=305)

In the first strip of panels, Lois has a strong visual presence. She fills the space of the first and third frames, while we sneak a barely legible peek at Clark Kent’s glasses and cleft chin. Lois is dressed professionally (and androgynously) with a blazer and tie, which adds a sense of corporate power. Although Lois only speaks twice, both minimally with the sarcastic sound of “mmhmm,” there’s a certain strength in the absence of her words. The mmhmm indicates a purposeful statement of annoyance, and at once shuts down the conversation. Mmhmm neither asks nor answers anything. It does not progress any action, which paradoxically puts the ultimate power of plot in Lois’ hands.

Lois continuously shows that she isn’t interested in Superman. No, not even a big secret can persuade her. In the third set of panels, Lois shows that she can play games, too, as in the panel when she beckons to Kent seductively, saying, “I have a secret, too. Psst, come here.” The lovesick Clark Kent falls for them every time. The feisty Lois we know and love responds with “You. Are In. My Goddamned Way.” This is the epitome of Kate’s kickass Lois, I think.

The next comic strip begins with Lois Lane on the phone with her mom. Suddenly, an absurdly large head of Superman pops through the window. “Lois, are you in trouble? I saw you on the phone. Just thought something was going on.” This comic scene certainly calls into question Superman’s judgment. In the 1972 Superman comic “Must There Be a Superman,” Superman considers that “Maybe I have been interfering unnecessarily! I decide what’s right or wrong…and then enforce my decision…by brute strength.” Does a superhero automatically have perfect judgment of justice? Beaton’s Lois Lane comic parodies Superman’s assumption and asks us to question, “Who is capable of saving themselves?” and even more, “Who is in trouble to begin with?”

Kate Beaton really had convinced me of Lois Lane’s badass-itude, until the last comic strip, in which Lois is at the White House in order to interview the president. Our girl has worked her way up through the journalism ladder and gotten herself to work on the story of all stories, when suddenly, SuperSnoop (I mean, Superman, eh-hem), busts the walls down and “saves” Lois. They fly into the air with Lois in Superman’s arms, and she yells, “What are you doing?” I was seriously upset that the comic ends on this note, because it reinforces the stupidity of some superheroes who “save” people who didn’t want to be saved, either because they actually think they are doing good, or in Beaton’s case, because Superman is depicted as a creepy lovesick stalker. Again, I can’t stop thinking of “The Incredibles” and this clip below, where Mr. Incredible gets sued for saving a man who tried to commit suicide and didn’t want to be saved. Even though Lois obviously was not trying to kill herself, this scene helps to explain how superheroes sometimes use their fame and strength to do things that aren’t in their victim’s best interests.

Perhaps Lois needs to have a talk with her lawyer! In any case, I enjoy Beaton’s delving into the female side of the Superman comics, which not only makes us look at Lois in a more positive light, it also turns the tables on the males of historic comics and continuously makes us wonder, “Must there be a Superman?”