“Inferiors revolt in order that they may be equal, and equals that they may be superior. Such is the state of mind which creates revolutions.”

— ARISTOTLE

“A superior man never fears death”

— KIM MAN-JUNG, The Nine Cloud Dream

P R O L O G U E

Summer

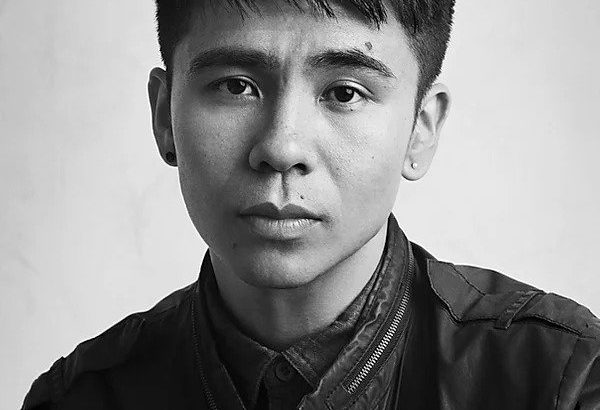

The gentle thrumming of acid rain could be heard between the sounds of screeching tires and shattered windows, and Porter could only watch quietly as blood soaked through Piper’s white dress shirt from a small wound, mixing with the rain and staining it a light pink. He studied her as she tied the small, opaque bag around the base of a large bamboo plant. The uprooted soil was already wet by the time she began to fix the potted bamboo back into place. The warm rain reflected a certain loneliness in her flax-colored eyes; the water droplets refracting like sparkling tears were an enchanting addition to her cool demeanor. Her jet-black hair that stuck itself to her face while she worked presented to him the image of a mother wolf peering through tall grass at unsuspecting prey.

Porter removed his dirty glasses to examine her more closely. She was beautiful in the rain.

The apartment room was sparsely decorated, neglect visible in various forms of debris. The roof was splintered open with blackened wood and frozen at a wicked angle, supported by charred stucco walls. With a sigh, Porter flopped onto the rusty bed frame beside the apartment’s broken window. He leaned backwards, letting himself fall through the space where a wall had once been, embracing the rain and letting it wet his face and body. He realized in this moment just how much his bones ached from the last few weeks. The pain went much deeper than bone. Above him, the ceiling was as high as the sky. He stretched his lanky arms toward the open gap in the building’s roof just as he had done in this exact spot many times before. Although the rain was coming down hard, he made no effort to shield his face or protect his vision. He relished the sting of acid in his eyes. Due to the clouds, the ceiling was lower than usual today, and he could nearly touch it.

What bothered Porter was not the stinging rain, the smell of sulfur melting the street, or the muted shouting on the horizon, but rather the pungent odor of charcoal flames and burning flesh which manifested itself only to him. With his eyes open, he smelled it in his mind. With his eyes closed, the scene recreated itself: the wall behind him was whole again, and behind that wall came a playful whistle, a golden laugh that could have tickled the heavens. He’d imagine himself standing before a pillar of smoke, a ball of fire. He’d imagine looking down at his wrists, zip tied to a stretcher. He could picture the California sun beating on the pavement, the stilled palm trees, and the gentle blue of a summer afternoon. When he opened his eyes again, the only sounds were rain and distant drums; the only sight a black, callous sky.

What Porter couldn’t have imagined is what Joel had said to him in that casual, offhand way he tended to do with his lazy eye trailing off in the distance. How quickly everything had changed. Fat chance, turning back now. Strangely, where once he felt anger and remorse now only felt like a calm surrender.

Piper kicked his foot, snapping him out of his reverie. “It’s time to get going.”

After one last glimpse at the flat horizon, purple as a bruise, Porter straightened himself and followed Piper out of the abandoned apartment complex, their footsteps squishing on the wet carpet. The dog was outside the door licking its nuts when Porter clicked his tongue, and it popped up immediately. Duke nuzzled into Porter’s good leg, his tail wagging nervously.

* * *

The flooding streets only added to the existing chaos; the city’s lousy sewage systems weren’t equipped to handle large amounts of water, especially not for the worst storm in its history. Summer break for the students of Bursa County High would not be the usual blunt and uneventful sunshine, but rather a swamp of rainy days in a budding warzone. As the van edged closer and closer to the sound of distant violence, a growing number of dumpster fires began to speckle the early morning horizon like Christmas lights. Despite it all, the crew was chatting idly in the backseats, not seeming to comprehend the impossible pressure building within the city limits.

Porter leaned against the passenger window and propped his feet on the dash, watching the world drown as it whizzed past him. He noticed how everything seemed to shine more brightly in the rain. The reflections of red streetlights, fluorescent signs, and flashing police sirens on waterlogged roads painted the city with more color than he had ever seen. Electric neon lights stretched across the buildings and asphalt like bright oil pastels on a sheet of water. Arrays of backlit signs and the glow of West Bush Cinema’s vertical display streaked the dark empty street like a fever dream, fueling the city with a warm energy Porter thought had been lost long ago.

The first one went graceful and fast. The second not so much. Piper was laying in the trunk with Duke curled up beside her, pressing a rag to her gash when they arrived at Valenta Street. She propped herself up and winked in Porter’s direction, giving Duke a pat on the head. Duke whined and shifted uneasily on his front paws. Porter watched as she slipped wordlessly through the trunk and vanished into the darkness.

Cooper was already complaining before we pulled up to Asherton, but that was to be expected. “You know what we have to do,” said Porter dryly, tapping his wrist where a watch might have been. “It seems you are running out of moonlight, Mr. Hayes.”

Not without a mumble and a curse or two, Cooper hopped out of the car with a splash, loping around the corner with his backpack full of trinkets jingling and a string dangling loose behind him.

* * *

They finally arrived at Porter’s stop, a damp underpass. He wiped his glasses with the inside of his shirt out of habit. When he got out, Duke started whining anxiously.

“Don’t worry boy,” he said, rubbing the dog under its ears, to which it gave a loud bark. Porter smiled and pressed his nose to Duke’s. “I’ll be back before you know it.”

As the van drove off with a noisy dog in tow, Porter found himself alone with the rain as it fell over the archway like a watery curtain. He sat himself down on the cold sidewalk and hugged his knees, rocking back and forth, simply observing. It was a position he found himself in very frequently these days. To his mild surprise, he had been dropped off at Sunset Tunnel, a spot which provided convenient shelter from the rain, but more notably was home to years and years of colorful graffiti scribbled on its leisurely sloped walls. Illuminated by a nearby streetlamp, the torrential rain blended with the myriad of rainbow designs to give off a vaguely preternatural effect—words of hope, words of love, words of goodbye—some scuffed and some brand new, mostly tagged by people he had known at one point. A long time ago, Porter had tagged something of his own here, but he was sure it was covered by now and didn’t bother to look.

As a rule, Porter tried not to contemplate things too much anymore, but these moments lent themselves to the occasion rather nicely. In the span of a few days, the world he knew had fallen victim to the disease which had infected his own life on and off for many years. Though it seemed to have resurfaced only recently, it had been festering for much longer than that. By the time Porter caught the disease of this city, or at least when he had diagnosed himself, the time frame for an antidote had long since passed. He remembered a time when he hadn’t succumbed to the chaotic sickness and still lived untouched in ignorant bliss. He sometimes wanted to close his eyes forever and live only in those moments, asleep within his thoughts. But he steeled his nerves and inhaled the acidic rain-washed air. He must be forever watchful for the day when he’d get his chance to wake up from this beautiful, twisted dream.

Porter had only to look directly ahead to see the dream coming once again to pluck him from reality. This time it came in the shape of headlights, a familiar car rolling slowly to a halt beside him.

“Oh hello,” said Porter, smiling. “I wasn’t expecting to see you here.”