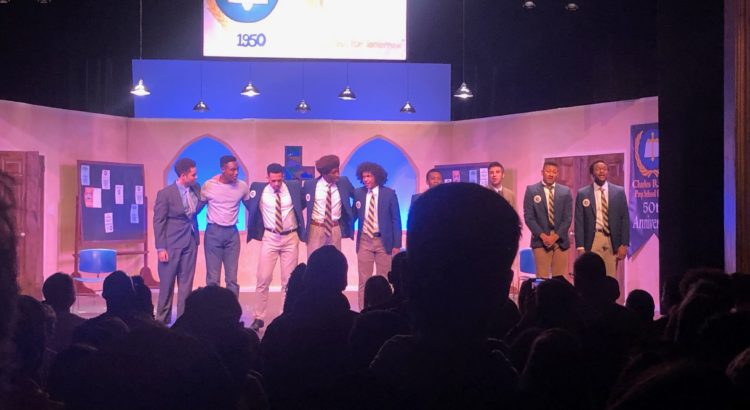

The subtitle “…A moving story of sexuality, race, hope, gospel music, and a young gay man finding his voice” was already enough to get me to the Lydia Mendelssohn Theater on a Saturday night to see this play. Then I found out that Choir Boy was written by Tarell Alvin McCraney, the Academy Award-winning writer of the film Moonlight, and I was doubly sold. Something to know about me: I love any chance to walk in someone else’s shoes for a bit, especially those with vastly different stories than mine.

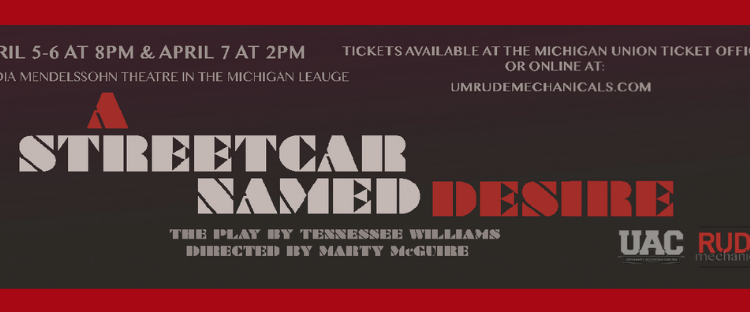

This production was put on by Rude Mechanicals, a student-run theater group on campus. They produce one play a semester and run everything themselves, from costumes to set design to the actors and crew. This was the first Rude Mechanicals production I’d ever been to and I was impressed. The trailer they made for the play was really cool and just shows how much work they put into it:

I won’t spoil the plot for anyone who has yet to see this gem of a play, but I will say that it is so very RELEVANT. A recurring theme throughout the story is intimacy: who gets deprived of it in society, who you’re allowed to have it with. The actors were so incredibly talented and displayed the intimacy of the play so well. My favorite character was Anthony, the main character’s roommate, for this reason. Whenever the cast sang together it filled the entire theater and gave me chills. They harmonized like they could do it in their sleep. The audience was super into it – cheering and clapping after each musical number, ooh-ing in sympathy when characters got hurt, hmm-ing to the lines of dialogue that struck the deepest.

I will say that I don’t think this was a very accessible production. None of the performers wore microphones which made it hard to hear them at times, especially when they were speaking with their backs to the audience. More than once I would hear the audience burst out into laughter around me and wonder what joke I had just missed on stage. The seating arrangement of the Lydia Mendelssohn theater is also not my favorite and isn’t tiered in a way that allows you to see the stage well from the rows that are not at the front. It’s a historic theater which is something to keep in mind. All in all I think the students did what they could with the space they had.

I will say that I don’t think this was a very accessible production. None of the performers wore microphones which made it hard to hear them at times, especially when they were speaking with their backs to the audience. More than once I would hear the audience burst out into laughter around me and wonder what joke I had just missed on stage. The seating arrangement of the Lydia Mendelssohn theater is also not my favorite and isn’t tiered in a way that allows you to see the stage well from the rows that are not at the front. It’s a historic theater which is something to keep in mind. All in all I think the students did what they could with the space they had.

If you have a chance to go see the Rude Mechanicals’ production of Animal Farm next March, I highly recommend you take it!