If you look David Mitchell up on any website, davidmitchellbooks.com or his Paris Review interview, there is rarely an author picture attached to it. It’s as if his image does not carry any weight in his success, just his words and the characters’ stories he creates. He is a god lingering underneath the surface of the text. We can imagine a bit of the author through the page, but it’s cloudy.

And then, like magic, there he was in human form, sitting before the pews of the United Methodist Church on State Street, as part of the Zell Visiting Writers Series. No longer was he a dismembered hand writing lyrical fiction with ink – he was a MAN in jeans and smiling and laughing and breathing. The author who brought us Cloud Atlas, Number9dream, Black Swan Green, and The Bone Clocks, was here to draw up once more a new masterpiece of its kind, Slade House.

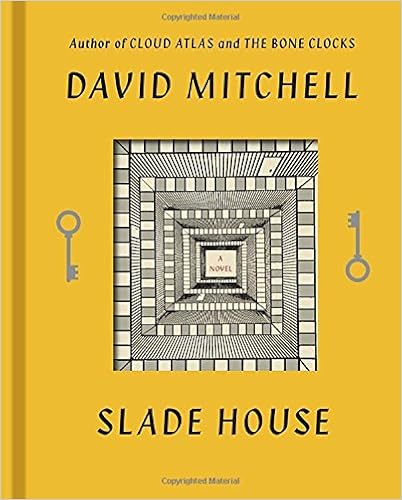

The book itself is square and fits comfortably in hands. With a little cut-out square in the cover, a vortex-like labyrinth of an elevator shaft stretches out and away into an abyss that is deep inside the book. It immediately presents itself as one of those portable books that you are going to want to take everywhere with you; a book that you will hold up proudly in front of your face to show off, “Hey look what I’m reading.”

The story threads together five lives of the mysterious Slade House residents, each story separated by nine years in time. Who’s inside? A precocious teenager, a recently divorced policeman, a shy college student, people who live. And ghosts… Yes, David Mitchell has written a sort of ghost story. And I’m itching to read it.

First, David told us to close our eyes and imagine that he was 13 years old, a boy named Nathan, and (as they say in Fantastic Mr. Fox) *whistle* different.

He then went on to read with the most expression I’ve seen from most authors. As an expressive and emotive reader myself, I fully appreciated Mitchell’s performance. And it was just that – a performance. He got into character so much, that I almost felt like I was Nathan’s thoughts being fired from the synapse as quickly as Mitchell was speaking them. The stream of consciousness style allowed Mitchell to play with the speed and sentence structure of the words – at times, he could read slow and add facial expressions (e.g. Charlie Brown confusion, extreme joy); other times when the sentence was page-long and a mental mess of conjunctions and fragmented thoughts, Mitchell flew through without a breath, showing the urgency of the fragile teenage brain.

Oh, it was a glorious reading – the audience let out a little “aww” when it stopped. There’s something so wonderful about being read to, especially someone who is passionate about the reading. Even in a large gathering place like a church, you almost blur everyone else out so it’s just you, your ears, and the sound waves of words that sing to you.

After the reading, one of my own English professors, Peter Ho Davies, had the honor of mediating a short Q + A (or perhaps David Mitchell had the honor of being asked by Peter!) One thing that Peter mentioned that I had never known was the fact that David had created his own little universe, not unlike Tolkien’s Middle Earth. By universe, he meant that characters who appear in one novel can guest star in other novels later on. For example, the musician’s young daughter in Cloud Atlas grew up to be “the perfect fit” to play the 70 year old mentor in another one of his novels. “Writers are horribly lazy – we’re always trying to find shortcuts,” David modestly says. He reminisced of Shakespeare’s depiction of Falstaff, who appears in 1 Henry iv, and was so much loved by Queen Elizabeth, that she demanded him to have his own play. So, never one to deny a queen, Shakespeare agreed to create the “Merry Wives of Windsor,” starring none other than Sir John Falstaff. And this, bringing characters back into the world to tell other parts of their story is what Mitchell strives for.

Known for frequent “genre” switches, sometimes even within the same novel, Mitchell asserted that “he hates how mainstream literary writers aren’t allowed to go to genre places.” At that I had to give a loud whoop! Literary writers have been pigeon-holed into such tight confines by the publishing industry. They must be political, realistic, innovative, but not historical, not speculative, and definitely not fantastical. But, then, how did Dickens get away with it? And Orwell? And Huxley? Is it just the fact that there is Penguin Classics sticker on it that makes it okay to put in the “literary” section? Just because a bit of magic or psychological thrill occurs in a book does not mean that it is unrelatable, that the characters don’t understand real human emotion. These classic books wouldn’t exist without genre. And, perhaps, neither would his own. He proposed that novels of the future are hybrid creatures, like the duck-billed platypus. They can transport you through time to other places in the world simply through the language. Each book is its self-contained Narnia and are themselves a kind of “primitive, gorgeous, beautiful magic.”

Thank you, David, for sharing your book magic with us. Let no genre stop you from casting your linguistic charms upon this earth.

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!