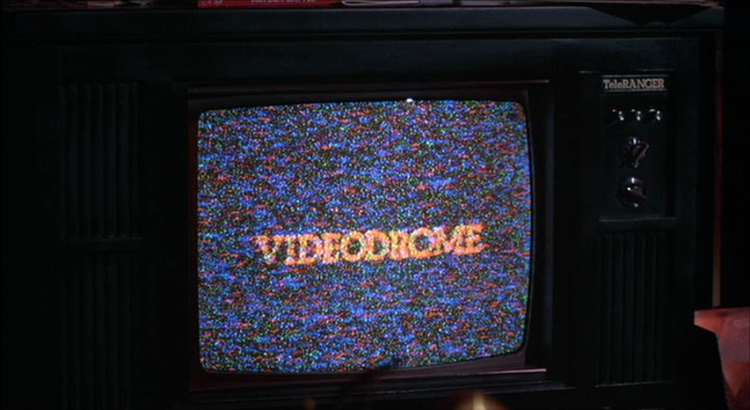

David Cronenberg is a filmmaker who knows exactly what he’s doing. He draws in the audience with his signature brand of body horror, then hits them with increasingly relevant social commentary. The cult classic Videodrome is a prime example of his approach.

Originally a box-office bomb, it’s gained a following due to its incredible special effects, dark themes, and oddball style. Categorized as science fiction horror, the film demands much more from the audience than one might expect from its genre. The story takes bizarre, surreal twists and turns, so it’s another one of those films that relies on the audience recognizing clues.

The main character, television executive Max Renn (James Woods), is constantly on the search for the most shocking show he can find to boost viewership. He isn’t opposed to violence, real or imagined. He’s also perfectly comfortable with showing adult content. When he stumbles upon a transmission of “Videodrome”, a show that consists exclusively of hyper-realistic torture, he makes it his mission to seek out the source of the show. The addition of a sadomasochistic damsel in distress (Debbie Harry), a chillingly familiar corporate villain (Leslie Carlson), and the daughter of a technological prophet of doom (Sonja Smits) add complexity to the discomfort.

As soon as Max is subjected to “Videodrome”, he unknowingly becomes complicit in a plot to permanently change the psyche of the public. Slave to the will of “Videodrome”, he becomes programmable in both a metaphorical and a very literal sense. He only realizes the danger he and Nicki Brand (Debbie Harry) are in when it’s too late. Slowly succumbing to constant hallucinations and the influence of various puppet masters, both Max and the audience begin to lose sight of what is real and what is imagined.

Videodrome asks how far we’re willing to go for the sake of entertainment. It disgusted me not only due to the gore, but also because it’s more relevant now than ever. The two key recurring themes of the film are desensitization and media control. Since Videodrome’s release in 1983, these concepts have only become more central to daily life. In the digital age, anyone has access to the darkest parts of life; simply open an incognito browser and the world is your grim, terrifying oyster.

It takes advantage of everything it can with an R rating. It’s grotesque, dreamlike — actually, more like nightmarish– and needs a second watch to fully appreciate. The nearly $6 million budget was one of the largest he’s ever had for a film, and it shows in all the effects he was able to pull off. Universal saw the success of his 1981 film Scanners and decided to take a chance, but unfortunately this didn’t end up benefiting them.

Videodrome has slowly but surely gained a fanbase, and I couldn’t be more pleased. Whether you’re intrigued by its message or just in it for the carnage, please give Cronenberg’s dystopian prophecy a chance.

“Death to Videodrome! Long live the new flesh!”