As I am sitting around the table for Thanksgiving Dinner, my grandma is telling me about her time as a stenographer. She told me about shorthand—where one can write lines and dashes in regards to the sounds being emitted in conversation. It made for scarily fast documentation and was ideal for recording conversations. My grandma had  been extremely gifted in this regard, as she could write in shorthand faster than people could talk. She told me stories of how her teachers in high school would speak as quickly as possible, switching the tone and pitch of their voices in attempts to throw her off. But my grandma would recite back to them exactly what was said. It was a phenomenal skill. She told me about Thanksgiving Dinners when she was kid. She would sit back with her steno pad and record her parents and relative speaking around the table. When they were done talking, she would recite the entire conversation back to them. I was engrossed. I had her write my name in shorthand. A six-character name—Justin—was reduced to two quick flicks of the wrist, resulting in something that looked like an italicized ‘h’. It was genius.

been extremely gifted in this regard, as she could write in shorthand faster than people could talk. She told me stories of how her teachers in high school would speak as quickly as possible, switching the tone and pitch of their voices in attempts to throw her off. But my grandma would recite back to them exactly what was said. It was a phenomenal skill. She told me about Thanksgiving Dinners when she was kid. She would sit back with her steno pad and record her parents and relative speaking around the table. When they were done talking, she would recite the entire conversation back to them. I was engrossed. I had her write my name in shorthand. A six-character name—Justin—was reduced to two quick flicks of the wrist, resulting in something that looked like an italicized ‘h’. It was genius.

As I got to thinking about shorthand, I started to wonder why it had died. Quick recording was definitely a highly-regarded need in the modern age—probably more so than ever. We want minimalistic accuracy. Shorter. Sweeter. Simpler. Communication is key to any aspect of life, and when it is elegantly frugal, it is most effective and beautiful. Why, then, did shorthand largely disappear? Or, more accurately, why was it never adopted for public use?

In the rise of social media and the digital transfer of information, most communication is done through text. Whether it be emailing, messaging, texting, tweeting, or whatever, a reliance on characters has become nearly unavoidable. As a result, people are writing much more. Not with the hands, as cursory handwriting has been eliminated from most education systems and printing has declined in neat/careful+ness, but through typing. People can type as fast as my grandma could write shorthand. On the surface, the move to typing would be common sense, as the text could be CTRL+C & CTRL+V <copy and pasted> infinitely many times. It could be reformatted and edited—if need be—and is written in uniform characters which would be readable by anyone. Anyone, that is, who can read the language of documentation. As character typing seems more effective, I feel that it loses the universal abilities of shorthand. If this style of writing was truly subjected to sounds alone, it could, potentially, be used to document the speaking of any language in perfect detail. By reading back the sounds, one could potentially recite any tongue. This is something characters cannot represent. In the English language, characters do not fully reconstruct sounds. Rather, they can stand in place of ideas or meanings.

With so much text-based communication, we often inject emotions and symbols (like the ever famous UNICODE SNOWMAN! ☃) 8^B <<< this is a nerd-face emoticon.

In a sense, this new form of life documentation is more natural and fluid. Formal conversations no longer require a stenographer. Anyone can pull out a smart-phone and text his/her thoughts to Twitter or Facebook or the tumbleweed rampant Google+. While we may not be recording conversations in a potentially universal medium, we are keeping an ongoing log of our lives and thoughts in the most efficient form possible.

While my grandma reminisces on writing shorthand on her steno-pad, I pull out my phone and tweet about the table conversations in 140 characters or less.

Elegance in the art resides in selecting those ≤ 140 characters.

It is a unique artistic display, as it takes the manipulation of objects into a visually pleasing performance. Juggling follows a pattern and that repetition is not only fluid and appealing, but the nature of the art. We enjoy seeing the flying balls, circling in arcs back to the thrower’s hands. The three-ball-cascade, the most basic and elemental of tosses, is a fluid and infinite loop that can be mesmerizing to viewers. Each ball completes the same cycle and receives an equal amount of attention from the juggler. It is a brilliant cycle of coordination, even at its most basic level. When advanced, the performance can become truly breathtaking.

It is a unique artistic display, as it takes the manipulation of objects into a visually pleasing performance. Juggling follows a pattern and that repetition is not only fluid and appealing, but the nature of the art. We enjoy seeing the flying balls, circling in arcs back to the thrower’s hands. The three-ball-cascade, the most basic and elemental of tosses, is a fluid and infinite loop that can be mesmerizing to viewers. Each ball completes the same cycle and receives an equal amount of attention from the juggler. It is a brilliant cycle of coordination, even at its most basic level. When advanced, the performance can become truly breathtaking. Nigel Poor

Nigel Poor Whether it be torching a copy of Fahrenheit 451 or separating black-and-white pages from The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, the process of recreating these books more powerfully captivates the original spirit of the work itself. Especially now in the information age, when physical books often go extinct for the more suitable online medium, the power of paper in a work is an attempt at reviving the spirit of physicality available in books. There is something about bookstores and libraries that is intrinsically pleasing in real life, as opposed to the digital medium. One can argue the aesthetic value of actually seeing the sheer volume of information available in a bound piece. When this body, this container for the substance within, is minimized to the visually unsubstantial work on a computer screen or digital reader, something is lost within the book. It is like a person being transformed into digital material, like on Facebook or Twitter or any other form of social media. The ideas—the spirit—of the person remains, as they can write their mind and demonstrate the thoughts swimming within via pictures and art and music and all these great things, but the container, the body, is not transferred. Therefore, it is not the same. We crave to meet people in person; which is why we still have interviews and keep restaurants and social gathering places in business. The body, our container, affects the content. Be it from body language or outward expressions of our personality—hairstyle, skin color, piercings, etc—our physical form has an effect on the thoughts within. This is what the banned book project plays upon.

Whether it be torching a copy of Fahrenheit 451 or separating black-and-white pages from The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, the process of recreating these books more powerfully captivates the original spirit of the work itself. Especially now in the information age, when physical books often go extinct for the more suitable online medium, the power of paper in a work is an attempt at reviving the spirit of physicality available in books. There is something about bookstores and libraries that is intrinsically pleasing in real life, as opposed to the digital medium. One can argue the aesthetic value of actually seeing the sheer volume of information available in a bound piece. When this body, this container for the substance within, is minimized to the visually unsubstantial work on a computer screen or digital reader, something is lost within the book. It is like a person being transformed into digital material, like on Facebook or Twitter or any other form of social media. The ideas—the spirit—of the person remains, as they can write their mind and demonstrate the thoughts swimming within via pictures and art and music and all these great things, but the container, the body, is not transferred. Therefore, it is not the same. We crave to meet people in person; which is why we still have interviews and keep restaurants and social gathering places in business. The body, our container, affects the content. Be it from body language or outward expressions of our personality—hairstyle, skin color, piercings, etc—our physical form has an effect on the thoughts within. This is what the banned book project plays upon.

They embody the power of the written word in a new shape, and provide a growing deviant of inspiration unachievable by simply the text itself. It gives new life to these formerly shackled pieces. It frees the book.

They embody the power of the written word in a new shape, and provide a growing deviant of inspiration unachievable by simply the text itself. It gives new life to these formerly shackled pieces. It frees the book.

Advertising creates clutter. Sides of highways are clustered with billboards waving at the thousands of drivers passing by each day. They are obstructive, bulky signs that stretch their wingspan over the surrounding trees to vie for attention. Advertisements coat the sides of websites, luring our eyes with distracting graphics and colors and mystery-inducing lines like “Language professors HATE him†and “1000th visitor! Click here to claim your free iPad†and “Meet sexy singles (like Ms. I-Swear-These-Aren’t-Implants-And-Every-User-Of-This-App-Looks-As-Sexy-As-I-Do).†They coat our cereal boxes, newspapers (for those old-timers out there), Facebook pages, daily commutes, etc. Each of these advertisements is in competition with each other, constantly swallowing massive amounts of revenue to become slightly better than their competitors. They pile up like layers of paint over a color-slut’s rented apartment. It is a desperate and futile, Sisyphean battle for our attention. As time moves on and we drown in their commercial rank, we become less willing to provide that attention.

Advertising creates clutter. Sides of highways are clustered with billboards waving at the thousands of drivers passing by each day. They are obstructive, bulky signs that stretch their wingspan over the surrounding trees to vie for attention. Advertisements coat the sides of websites, luring our eyes with distracting graphics and colors and mystery-inducing lines like “Language professors HATE him†and “1000th visitor! Click here to claim your free iPad†and “Meet sexy singles (like Ms. I-Swear-These-Aren’t-Implants-And-Every-User-Of-This-App-Looks-As-Sexy-As-I-Do).†They coat our cereal boxes, newspapers (for those old-timers out there), Facebook pages, daily commutes, etc. Each of these advertisements is in competition with each other, constantly swallowing massive amounts of revenue to become slightly better than their competitors. They pile up like layers of paint over a color-slut’s rented apartment. It is a desperate and futile, Sisyphean battle for our attention. As time moves on and we drown in their commercial rank, we become less willing to provide that attention. Like seriously, TMI. We don’t want any more pointless grains of information. We don’t want to be manipulated into spending our money a certain way. We don’t want to be

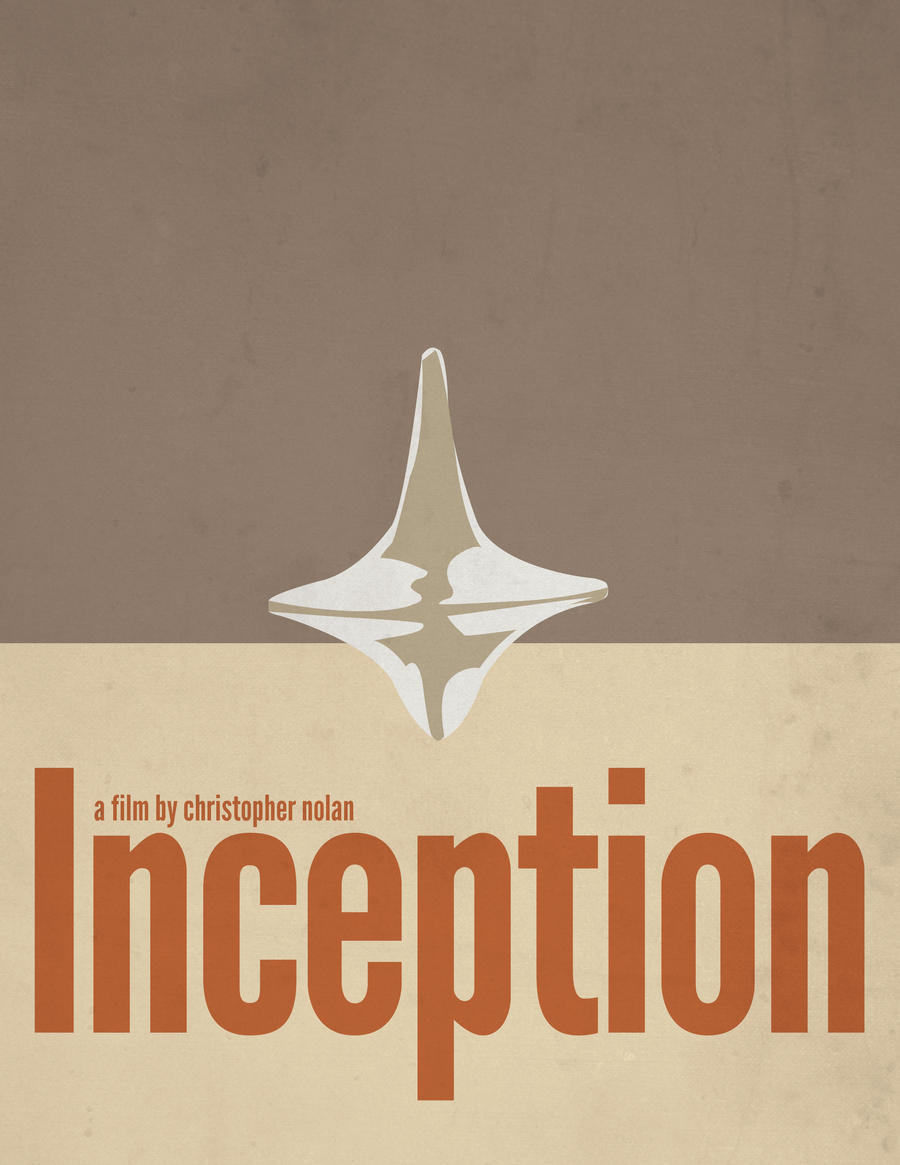

Like seriously, TMI. We don’t want any more pointless grains of information. We don’t want to be manipulated into spending our money a certain way. We don’t want to be  A new movement that seems to have been gaining footing in pop culture over the last few years is the design of minimalist posters. Movies and books and famous characters have been stripped down to iconic details and artistically portrayed in the simplest forms. Superheroes may be reduced to the shape of their mask. Great scientists may be trimmed down to a few crossed lines. Epic films may only contain a single object. This form of stripping down is art in its purest form. Like the naked body, untouched by makeup or product, not hidden behind a layer of cloth, shows the true beauty. It is fruit, freshly plucked from the tree. Unadorned, it is the most delectable.

A new movement that seems to have been gaining footing in pop culture over the last few years is the design of minimalist posters. Movies and books and famous characters have been stripped down to iconic details and artistically portrayed in the simplest forms. Superheroes may be reduced to the shape of their mask. Great scientists may be trimmed down to a few crossed lines. Epic films may only contain a single object. This form of stripping down is art in its purest form. Like the naked body, untouched by makeup or product, not hidden behind a layer of cloth, shows the true beauty. It is fruit, freshly plucked from the tree. Unadorned, it is the most delectable. Plus, these posters embody something that advertisements never can. A wholesomeness. A genuine appreciation for what the topic stands for. They are not trying to sway viewers into buying some product or conforming to some new trend, but simply provide something we can appreciate. It is simplifying an artifact of pop culture that would otherwise be overly bedazzled in manipulative tricks. The art of making the complicated simple is the threshold of beauty. Our attraction is sparked in the simplest of ways. We don’t like clutter, so show us the fruit.

Plus, these posters embody something that advertisements never can. A wholesomeness. A genuine appreciation for what the topic stands for. They are not trying to sway viewers into buying some product or conforming to some new trend, but simply provide something we can appreciate. It is simplifying an artifact of pop culture that would otherwise be overly bedazzled in manipulative tricks. The art of making the complicated simple is the threshold of beauty. Our attraction is sparked in the simplest of ways. We don’t like clutter, so show us the fruit. Throughout the spring and summer, I punch the clock at a greenhouse in the farming community of Allendale, Michigan. While there is little to no training given by the managers of the company, I am thrown into the indoor fields of flowering annuals like a clueless tourist being dumped into a foreign land. As the days drone on, I quickly learn the alternative names of plants and where they are located in the store. It is not long before I begin understanding care and maintenance procedures and their corresponding relations to other plants. I distinguish annuals from perennials, full-sun from part-sun from full-shade. Heat resistance and zoning become second nature to me. I can tell customers which plants attract butterflies and hummingbirds and which ones repel deer and mosquito. The complexity becomes beautiful and I find myself engrossed by the magic of plants. It is an enchantment I do not wish to flee.

Throughout the spring and summer, I punch the clock at a greenhouse in the farming community of Allendale, Michigan. While there is little to no training given by the managers of the company, I am thrown into the indoor fields of flowering annuals like a clueless tourist being dumped into a foreign land. As the days drone on, I quickly learn the alternative names of plants and where they are located in the store. It is not long before I begin understanding care and maintenance procedures and their corresponding relations to other plants. I distinguish annuals from perennials, full-sun from part-sun from full-shade. Heat resistance and zoning become second nature to me. I can tell customers which plants attract butterflies and hummingbirds and which ones repel deer and mosquito. The complexity becomes beautiful and I find myself engrossed by the magic of plants. It is an enchantment I do not wish to flee.