The childhood pursuit of creating fictional worlds never really goes away. The control one has over the geography, and then possibly peopling the landscape, is so very satisfying, so very full of potential. There are few enough constraints (the medium, the mind) to provide opportunities instead of options, but just enough to prevent creating something from scratch from being impossibly daunting. For a period of time when I was younger, drawing maps of imaginary lands could entertain me better than anything else. But free-range map-making does more than entertain; it’s creating, designing, building.

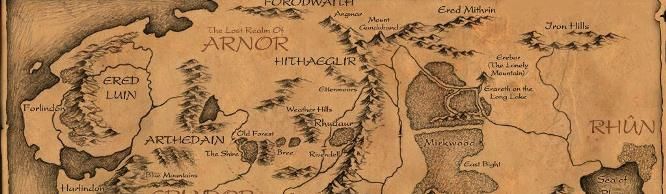

Author David Mitchell speaks to inventing maps as a child: “Those maps, I think, were my protonovels. I was reading Tolkien, and it was the maps as much as the text that floated my boat. What was happening behind these mountains where Frodo and company never went? What about the town along the edge of the sea? What kind of people lived there? The empty spaces required me to turn anthropologist-creator.â€

The idea of cartography as a sort of anthropology is an intriguing one. Miscellaneous land-forms sprung out of a blank page are all well and good, but they’re no good just sitting there. Characters are needed to traverse the lands, sail the seas. Worlds are experiential, but everyone experiences differently. So now, in addition to simple geography, you can fill in entire socio-political structures, civilizations and societies and peoples with their various dispositions and various histories. It’s one of the reasons works of fiction and fantasy often have the insides of their covers adorned with maps, I suspect— people and plotlines are tied to geography.

World-building also occurs in other formats, albeit more constrained ones, as in computer-based games with oddslot open formats. While there might be set goals as in any other game (completing tasks, finding objects, defeating enemies), the best part of the game is often building things, constructing your building or town or country. In fact, it might even that it is because of the restrictions the game’s parameters place on the player that makes being able to creatively and effectively build and create things so fulfilling.