Do you ever think of the spaces that you inhabit? The cafe? Your room? Your bathroom? Yes, basically everything is a “space.” But what defines a “space?” I would say that a space is a place that we inhabit in which its limits are usually defined by some sort of marking or is simply distinguished from other places via barriers. With that sort of Apparently, for example, a space can be private or public, or inviting versus uninviting. But what exactly makes us feel these certain vibes from these things we call “space” around us? Let’s ask these questions in terms of a garden.

A garden is typically defined as “a piece of ground, often near a house, used for growing flowers, fruit, or vegetables.” Fair enough, this is stereotypically its function. But, gardens can be self-owned, or it can be owned and shared by an institution. So what kind of space is a garden? Is it a public space, or is it private? What are your thoughts about this question? And what other spaces can be similarly questioned? Comment your thoughts! 🙂

Category: Uncategorized

Comics and Having Heroes

I love comics, especially the literary variety known as graphic novels. I was ecstatic when I heard that the art school was going to host a talk by none other than Art Spiegelman, the Pulitzer Prize-winning comics artist, as part of the Stamps Distinguished Speaker Series. He solidified the genre of the graphic novel with his work “Maus”, a gripping account of his father’s survival during the Holocaust with Jews depicted as mice and Nazis depicted as cats.

Spiegelman’s presentation was titled “Comics is the Yiddish of Art”, the thesis that drove his roughly 90-minute talk. He described his inspiration from the greats, starting with Superman creator Jack Kirby, a Jewish American like himself. As the talk went on, Spiegelman argued how comics were not just a home for Jewish American artists, but for outsiders in general. He compared the localized nature of Yiddish with the fluid grammar of comics as a visual medium. The unusual comparison felt justified and of personal interest to Spiegelman.

But his talk fell flat when he addressed the sexism and racism that has fueled comics for decades. After discussing how comics were condemned by authorities and even burned due to their provacotive content, he showed an example of how comics (by men) hid images of women’s groins and breasts in the background. This was followed by an anecdote of how he loved to draw women’s breasts and groins in junior high that he would then morph into the faces of dogs to avoid repercussion. This got a laugh out of the audience, but I was unsettled. The art professor who had introduced Spiegelman to the audience, the incredibly talented Phoebe Gloeckner of “Diary of a Teenage Girl” fame, had said she was interested in hearing the connection between Jewish identity and comics as she had always felt as an outsider due to being a woman cartoonist. The way Spiegelman showed comics’ history of objectifying women made it feel inevitable, as “boys will be boys”. I wondered if male cartoonists ever considered how their crass attitude to portraying women alienated their peers like Gloeckner.

His discussion on racism had a similar problem of perpetuating the stereotypes that keep diverse artists out of comics. While calling out the racist caricatures that became a foundation for comics, he showed how he made a cover full of racist caricatures for “Harper’s Bazaar” after Danish newspapers went under fire for depicting the prophet Muhammad, which is prohibited by Islam.

I was disappointed. Spiegelman spoke of his frustration with identity politics and his disillusionment in becoming a spokesperson of sorts for the Jewish community when he considers himself an artist first and foremost, leading me to believe he is against having art shoehorned due to the identity of its author. And yet he was continuing comics’ tradition of not being sensitive to the disrespect faced by people with marginalized identities in the art world.

I am cognizant that Spiegelman used coarse language with all social identities depicted in the art he included in his talk. He shared stories of being considered anti-Semitic for not portraying Jews or the Holocaust in a traditional way, a discussion best left to his own community. But as a Latina who is always striving to find representation in the media, I was not amused by his lack of interest in making comics a more inclusive medium. After his talk I was inspired to send an op-ed comic of my own to the Michigan Daily, and I finish this article with my head held high and hopeful of the future of diverse artists.

The Thrill of Sam Smith

The Thrill of it All, Sam Smith’s new album, was released on November 3. His sophomore record is a fourteen-track, forty-nine-minute journey through one of Smith’s favorite topics: heartbreak. As with his first album In the Lonely Hour, The Thrill of it All first and foremost features Smith’s voice, forgoing the electronic beats and synthesizers popular in music today. Smith is accompanied by a piano and supported by a choir, creating a lush soundscape in which he cries. His lyrics are sad, self-pitying, and melancholic, and his melodies both predictable in their tone color and astonishing in their virtuosity.

While the overall color and feel of his two albums might feel very similar, the way in which Smith deals with his subject matter is very different. In the Lonely Hour was very much a record of self-reflection. His songs were about Smith and his own experiences, his own feelings, his own loneliness. While this is holds partly true in The Thrill of it All, Smith expands his definition of heartbreak: he still sings about pining after an unrequited love and losing a love, but also addresses issues of acceptance of the LGBTQ+ community and feeling hopeless in regards to current events and disasters.

For example, in Smith’s song “HIM”, Smith tells the fictional yet relatable story of a young boy from Mississippi coming out to his father. He sings both to his biological father and his “Holy Father,” which might be assumed to be God because of Smith’s strong Catholic background. This song is especially important in this album because in In the Lonely Hour, Smith was very careful not use any pronouns when speaking about another person. He wanted to be known as “Sam Smith the singer who happens to be gay” and not “Sam Smith the gay singer.”

In a New York Times profile published two days before the release of Smith’s album, Taffy Brodesser-Akner writes that

“He [Smith] realized two things. One was that he was ready to make a second album. The other thing was that coming out as gay wasn’t enough. He now understood that every visible gay person still had a leadership role. He now understood that he wasn’t operating on his own, but that he lived in context to a community whether he’d realized it or not. No, having come out as a gay singer, he realized it was now time to come out as a gay man.”

This realization that he, as a public figure, had an important voice and a responsibility to use it is present through the whole album. His songs are still catchy and relatable; his first single “Too Good at Goodbyes” is reminiscent of “Stay With Me” and “I’m Not the Only One.” However, his goal on this album seems to be to reveal his own personal feelings in his work rather than create work to fit a generic, sad-pop-ballad mold. That realization is a solid step forward for Sam Smith, and allowed him to create a decent sophomore album. His sound may be the same, but it is on the road to change and ultimately growth.

What’s Your Study Playlist?

There are many components to the perfect study environment. How many people are there? What is the temperature? Are you wearing comfortable clothes? Can you fall asleep in your study position? Will you be hungry and need to move soon? And lastly, what type of music do you want? The answers to all of these questions will differ per person. Some people like to study in groups and others alone. It also depends on what a person is studying for on what type of environment they want.

Most college students listen to something when they study; Whether that’s music, tv or something else. The music that people listen to differs based on the subject and type of homework that they are doing. The one thing that most people have in common is that they don’t want to have to sing along to the songs as they are studying because that easily distracts them. This means that you need a different playlist for studying than for driving, where the whole goal is to perform a concert in your car. People try to achieve this goal in different ways. It’s hard to find a balance between music to listen to for fun and music to listen to for studying.

This is because you don’t want to listen to music that you know and like to dance to when you should be concentrating on calculus. Some people listen to music in another language so that they are not tempted to sing along and they just listen to it in the background. Others listen to a different genre of music that they don’t know well so that they can’t be too distracted by it. Another option is listening to instrumental music.

Once you figure out what type of words you want in your study music, you then have to decide how slow or fast you want the music to be. Perhaps you want it fast to keep you awake when you are reading a particularly boring textbook, or you want it slow when you are trying to concentrate on a long specific problem. You also need to choose if the music is relaxing or intense, or upbeat, slow, or somewhere in between. All of these decisions depend on the type of work you are doing at the time and can also vary depending on your mood. The seemingly simple task of choosing a playlist to study is actually much more complicated than you initially think.

Finding Your Outlet

You know this feeling. I don’t like to even say the word because the more you say it, the more power it acquires…yeah, we all know it: stress. Let me tell you though, stress is a real thing, but to feel stress is a choice. Maybe your hair starts to fall out, you can’t focus on one thing at a time because you’re mind is expelling 360 degrees around you. Maybe you break down and cry. These are alternative ways to release the tension that has piled up inside you. However, I have good news. There are other, more pleasant ways to expel these feelings…that not only cleanse your mind of life’s stressors, but add some of life’s gifts.

So here’s how to find what stress cleanser works best for you.

Start with what you are given.

We have five senses. These are our connection to the world. Reciprocally, that is how we channel ourselves to the world. When we don’t channel ourselves to the world, our minds bottle up stress. For artists, they can put their thoughts into an image. For musicians, they put their thoughts into a sound. For chefs, they put their thoughts into a taste. Gardeners can put theirs into organized smells. For athletes, they put their thoughts into feelings of physical strength.

Pick a favorite.

You blast your music through your cheap white apple headphones on the way to class? You’ll pick your sense sound. Say you’re not terribly musically inclined, but you have an appreciation for music, so your outlet may be browsing soundcloud for 20 minutes between studying for subjects. So instead of screaming into your sweatshirt, you’ll find relief AND find new music! See what works for you.

Life’s too good to be stressed.

When Art Horror Isn’t Scary

This October I enthusiastically got into the spirit of the holidays by catching up on highly-acclaimed art horror films that have been released within the last decade. These included “The Babadook” (2014), “It Follows” (2015) and “The Witch” (2015). But there was one problem: these scary movies weren’t really that scary. Disappointed by this revelation, I looked up movie reviews of these films and was surprised to find out they were all belittled as “not scary” by people on the Internet when they first came out. It made me wonder what I expected from scary movies in the first place that made these otherwise excellent films disappoint me.

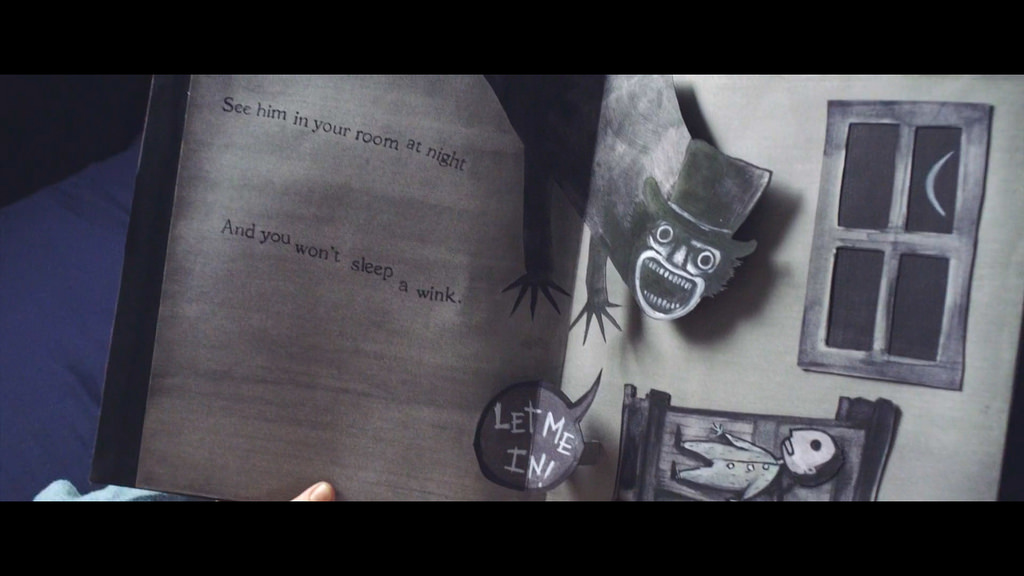

The main issue was jump scares. I had always considered myself a refined movie goer who could stand the lengthy plot development that puts my parents to sleep. But the 90 minutes that these three films clock in at don’t live up to the anticipation I had when I started watching them. In all three cases, we are given a horrific illustration of the antagonist’s evil powers right at the beginning that captures your attention immediately. But little information about these supernatural creatures is then given. The main characters are then left to debate about whether or not these monsters even exist as they confront fate and encounter these evil forces. This puts the viewer in an awkward position. We see the witch use baby Samuel for his blood. We see the Babadook worm his way inside the mother’s body. We see “it”, in a shocking turn of events, follow.

And yet the movie suffers from not letting the monster at the center breathe life into the plot by rearing their ugly head. You cannot deny how real and scary the threat posed by the antagonists in these films are. You know that the main characters are wrong to shake it off. And yet their false hopes that nothing is out of the ordinary carries weight. They have not yet encountered their demons head on, and since we see what they see we can understand why they would not consider the possibility they are being haunting by the supernatural. By not including jump scares to make the antagonists’ constant threat palpable, these movies force you to focus on the character development as the conflict fueling the plot comes to a climax.

The antagonist always returns at the end of the film, proving the dread that I felt the entire time I was watching these movies was valid. This confrontation at the end allows for the protagonist to unlock their true power, concluding with the main characters overcoming obstacles in making peace with their flaws that sparked the antagonists’ haunting in the first place. Thomasin in “The Witch” dives in to her lack of faith, only to become capable of supporting herself when her struggling family is unable to. The mother and son in “The Babadook” learn to coexist with the grief manifested in the Babadook. Jaime brazenly ignores “it” following her at the end of “It Follows” when she walks with her arms linked with Paul, demonstrating a sense of strength that comes from feeling supported by people who care about you. These endings may have left me unsatisfied as a horror fan. What’s the point of spending the entire movie with the protagonists defending themselves from the monsters if they are unsuccessful anyway? And yet by making the plots of these horror movies more nuanced, it allows film to depict deeply human emotions in a creative way.

I support the trend of these art horror films resisting cheap scares to further develop their characters and their struggles instead. While it may take away from the visceral roller coaster of emotions you have while watching a horror movie, the quieter, more intimate moments of human emotion that are being tapped into make it worth it.