The species that is known as the “creative writer” is one that has baffled me for centuries. Ranging from the hipster elite to that kid buried deep in Lord of the Rings lore, the creative writer takes all shapes and forms.

But really, can I criticize?

The creative writer (aka, me) just encountered her first workshop today. Terrified, she walked into class, prepared for the worst. They hated it, they didn’t understand the point, they wanted to burn the very words off the page. The creative writer had to sit, never explaining her decisions or why the poems were written that specific way, only drinking in the criticisms.

She dismissed the praise. They were lying, they only wanted a good thing to say so the bad things didn’t sound so bad. The things they liked were meaningless.

She rifled through the letters they gave her, reading every word for its double meaning. She wanted an excuse to rip up the pages and never look at them again. She searched, finding the critiques and holding them tight.

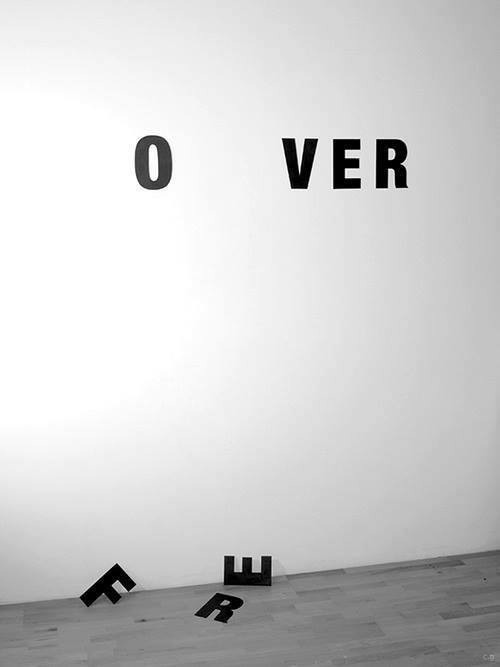

This is the life of a creative writer, the life I’ve chosen. Sometimes, I am happy with my choice. I love writing, I love reading, I love words. But most of the time, I am looking for that one glitch that is telling me that I’m not good enough to get published.

But now, I’m sitting in Hatcher. There’s nothing but me and my laptop. And so, to take a break from work, I pulled up Spotify, and decided to listen to one of my favorite albums from last year.

There are two versions of “The North” by Stars from their album of the same name. One is the normal version, the other, a bonus track, eloquently named “Breakglass Version.” This acoustic song has always been something that touched me, so as I sat, I thought of my piece, my classmates, and my future. But then I listened to the original track, and I realized that this version was sung by a different (male) member of the band. There’s always two ways to look at something, and one isn’t necessarily as bad as the other. It sounds (and probably is) very cliché, but just remembering that one simple fact helped me to breathe a little bit easier as I realized not everyone had to love my writing, and not everyone hated it. And that was okay.