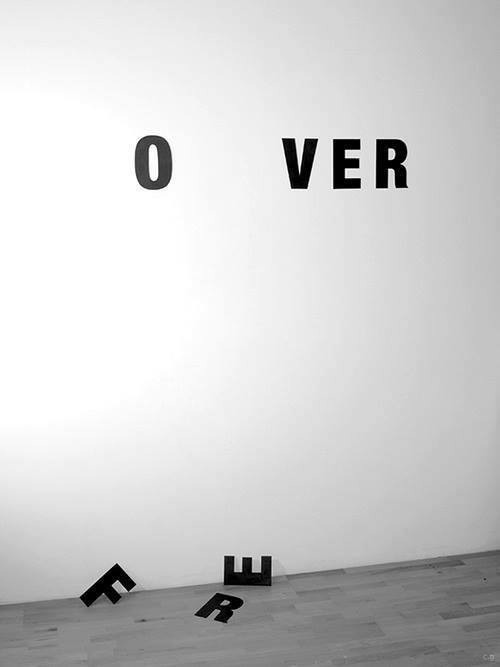

By now, everyone knows who Banksy is. Well, everyone knows that nobody knows, at least. We’re familiar with his playful and sometimes sharply poignant street art, ranging from simple stencils to elaborate installation; we’ve probably heard of his critically debated documentary Exit Through the Gift Shop. And if we keep up with the Times, we may be aware of his current stay in the Big Apple, described in his own words as “an artist’s residency on the streets of New York†(banksyny.com). It’s titled Better Out Than In, and he’s promised to procure one piece of street art for every day of the month this October. That leaves us 28 artworks in, having witnessed the true variety of Banksy’s creative language. We’ve seen his classic layered stencils, plain stencils, stencils that span across cars and walls, stencils for sale in Central Park; a garden growing in the back of a truck, sad stuffed animals trapped in the back of a different truck driving around the meatpacking district, and a 1/36th scale model of the great Sphinx of Giza made from smashed cinderblocks. He’s even published an article in the New York Times as a replacement for an op-ed column. In essence, the city has been Banksy’s for the past four weeks – as a temporary shelter, hideout, workspace, and playground all at once.

I could talk all day about Banksy. Everything he does challenges the very function of art in today’s society, as well as the role of the artist. He’s an outcast and likes it that way; he’s clearly not in it for the fame or money (neither of which are honest representations of creative success anyway), and he lets the work speak for itself. This is evident in the way he’s gone about “practicing†art in his own distinct, playfully intelligent manner, as well as how he’s acted upon and publicized this self-imposed exhibition. It’s the exact opposite of a traditional “residencyâ€, wherein the artist applies for a position in a studio or university and is either accepted or rejected based on whatever criteria are set by the institution. In this case, the artist is in control of his own fate, avoiding every formality that has come to follow an academic approach to creative work. The only price he has to pay is that of the law, which is easy to forget when we’re talking about street art these days.

Amidst all of the creative bounds that Banksy has leapt throughout his career as a vandal, it seems as though he’s on the verge of a new transformation. While the majority of Better Out Than In has still been expressed in his native tongue, the weight of the exhibition rests on the sculptural and performance-based installations like the trucks and mock gallery spaces. In fact, more than one of his posted stencils had me wondering if they were really his work – they seemed as afterthoughts, sentences left hanging in bits across town. They feel like the filler for these larger “happeningsâ€, in a sense, which one would assume require a larger amount of planning and preparation. What can we expect next from the most famous tagger to date? A spectacular finale on the 31st? The grand unveiling of his (or her, just so we’re clear) identity? One thing is for certain: the city will miss the attention when (s)he’s gone, if (s)he was ever really there in the first place…