I love a good laugh, but I’m a tough critic. As a result, it can be hard for me to find a nice comedy to watch when too many that get heavily promoted are gross or overtly problematic. What has shocked me in my question to find smart comedy is when the comedy doesn’t look like comedy at all.

My first experience with this paradox was in 2003, when I was around four. One afternoon my parents, cultured as they were, mistakenly rented the French animated film “The Triplettes of Belleville” for me and my even younger brothers to watch. They had rented “Finding Nemo” as well. I clearly remember my parents leaving my brothers and I with my grandmother with the request that we try to watch the French film first since we had already seen so many Pixar movies. I eagerly put on “The Triplettes of Belleville”, wanting to not only obey my parents but to watch that little clownfish be found by his dad again.

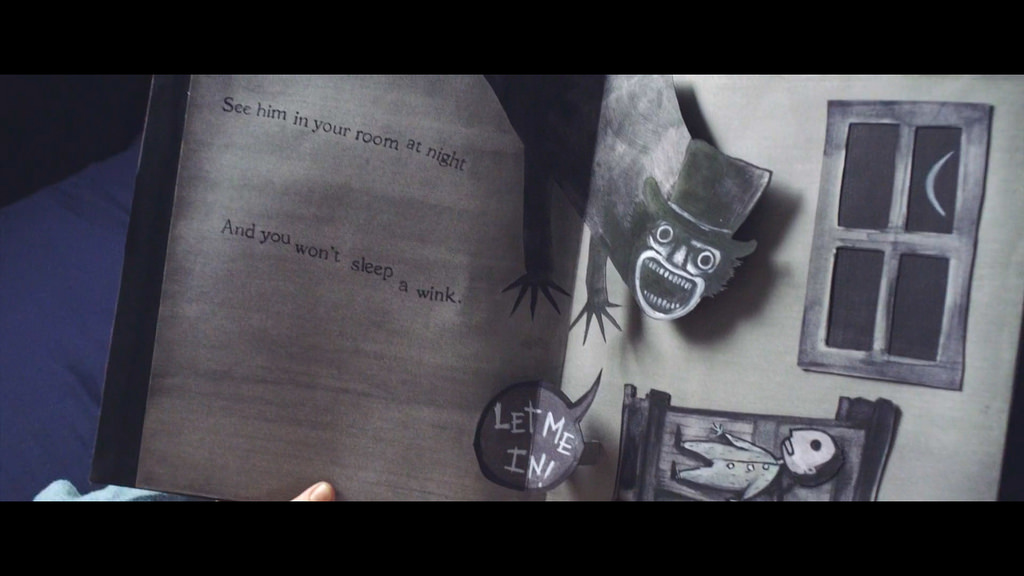

I was horrified by the French film. The bleak world depicted by animator Sylvain Chomet was depressing, and most of the characters looked evil. The French song featured in the film “Belleville Rendez-vous” was unintelligible to me at the time, but the wailing notes matched with the nightmarish art of the movie was enough to send me over the edge. I stopped the movie within five minutes and made my case that he movie was horrifying to my parents. I watched it all of 14 years later at age 20 and was again scared watching it, not surprised to learn that it is rated PG-13.

The plot is notably minimalist with little if any dialogue: a presumably French cyclist raised by his supportive grandmother has his chance to make his dream of becoming a champion cyclist come true, until he is kidnapped by what looks like the French mafia and held captive in Belleville, a faux New York City filled with stereotypical fat Americans. His grandmother comes to his rescue, accompanied by three aged, former singers known as the titular triplets of Belleville.

What kept my attention throughout the movie was the varied yet scary character designs. They are hellish, from the deformed cyclist’s incredibly muscular legs legs somehow connected to his terribly thin torso, to the closed eyes and hunched shoulders of the witch-like triplets of Belleville. The dark colors and sketchy figures present in this world, from sexualized prostitutes to grim-faced gunmen who kill in cold-blood, added to the fear factor. And yet, to my surprise, the film is labelled a comedy! I concede that the whimsical way the plot is developed in “The Triplets of Belleville” explains its classification.

I believe “The Triplets of Belleville” is an anomaly as far as comedy films go, as other comedy films I have watched that have been questioned for their humor have made me laugh. One is this year’s smash success “Get Out”, which has recently stirred controversy because it was entered as a submission to the comedy category for best picture at the Golden Globes. The plot was so nuanced and developed that it did not feel like it depended on humor to succeed per se, but it did make the film incredibly unique by masterfully intertwining the two genres. And, every joke was uproariously on point. But it is a horror film at heart, and I can understand why the comedy label may feel a bit of a stretch, even though there is no horror category that it can be submitted to.

This made me think of another film that was deemed too dark for a comedy: the 1971 film “Harold and Maude”, a romantic comedy-drama about a 20-year-old man obsessed with death and a 79-year-old woman who loves life (an old manic pixie dream girl, if you will). Roger Ebert panned the film, giving it one and a half stars out of four saying: “Death can be as funny as most things in life, I suppose, but not the way Harold and Maude go about it.” I was horrified by the beginning when our protagonist simulates hanging himself, and would jump when I saw how his subsequent suicide “attempts” become increasingly outlandish as he scares off potential girlfriends arranged by his unfazed mother. And yet the comedy of seeing the varied reactions from the interested girls was captivating, and built up to the climax when (spoiler alert) Harold loses the love of his life to suicide. This was the moment I learned the meaning of black comedy, as I pealed with laughter at the same time I cupped my mouth in horror and sank in my seat out of sadness. I respect Ebert’s opinion informed by his near-encyclopedic knowledge of film, but I do believe more credit is due to a movie that pulls off such a remarkable feat.

In conclusion, I do not know what to make of these comedy films that struck me as unusual. Their dark styles do not hinder the message of their plots, but still made me uneasy while watching. I believe this is symptomatic of merging different elements of the comedic with the tragic, and I look forward to seeing even more genre-bending comedies as I continue my quest for a good laugh.