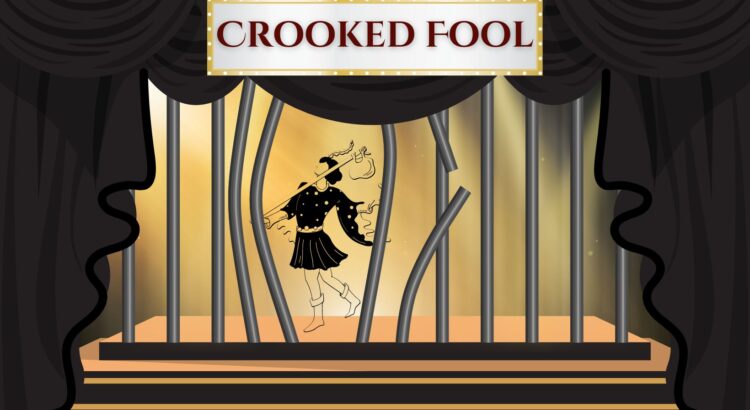

When I started physical theatre school a year after having basically my entire spine surgically relocated, one of my classmates was quick to say, “When we study Commedia Dell’arte, there will be certain things you can’t do. You probably couldn’t do Arlecchino.”

For context, Arlecchino is a stock character known for acrobatics and over the top physicality.

I did eventually play Arlecchino. I ultimately found a character I felt more at home with, but I still did it.

To be honest, that comment pissed me off. I put that Arlecchino mask on out of pure spite. It also pisses me off when I struggle to nail a dance skill because of my back and somebody says “just don’t do that one.” Or when I go to a yoga class and somebody finds out my spine is full of metal and held together with rope, and they automatically recommend an easier class.

I want to make this very clear: when somebody with a medical condition, disability, or any other need tries to do something, the answer should never be “just don’t do it.” They should never be sent out of the room. The choice to participate in an activity is theirs, not yours.

The answer to a theatre student healing from a back surgery is not to deny them the opportunity to learn the same things as everyone else. The answer to somebody who needs an accommodation to play a character is not that they shouldn’t play that character.

Creative spaces have evolved to be exclusive. Our culture has historically included Disabled folks from public life, including the arts, so industry norms have not evolved to meet diverse needs. When we send somebody away because their bodies or minds don’t meet our standards, we are perpetuating that exclusion. We become the oppressors.

When I push back against meeting access needs in performing arts spaces, I hear a lot of “we can’t compromise our creative vision” or “it has to be this way.” But…does it really? Or is that just what’s easiest for those who hold power in the space? Just because something is doesn’t mean it has to be.

Excluding someone does not preserve creativity. To paraphrase disability activists Terry Galloway and Donna Marie Nudd, what it actually does is demonstrate that you are not or do not want to be creative enough to come up with a solution. If we can make an entire show from scratch, we can problem solve.

I am a stubborn person and I show up in a lot of spaces where people aren’t expecting someone like me, and sometimes where they don’t want me. And I won’t leave to make things easier on those who don’t have to question whether they belong in the space. I value creativity too much to throw it out like that.