Saturday’s performance by the Ann Arbor Symphony Orchestra was celebration of the number nine: The program included Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 9 in E-flat major, Op. 70, as well as Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125. Appropriately, this concert was the conclusion of a season that marked the Ann Arbor Symphony’s 9th decade (90th anniversary!).

However, although both pieces were their respective composer’s 9th symphony, the difference between them is clear. Shostakovich 9, composed just after the end of World War II in 1945, is a whimsical piece, but with, in my opinion, very little melodic material. The composer himself noted that “It is a merry little piece – musicians will love to play it and critics will love to bash it.” I certainly did not leave Hill Auditorium humming motives from Shostakovich’s 9th symphony, but the piece gave me the feeling that it was depicting something electric and fleeting, like fireflies in the dark of night. I also did enjoy the plaintive clarinet solo in the opening of the 2nd movement, “Moderato.” However, it seemed to me as if the piece lacked the energy that I, as a listener, wanted it to have, and I am not entirely sure whether it was the actual score of the music, or the performance of it, that caused me to feel this way.

In contrast, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 contains what is probably one of the most recognizable melodies in all of music. Even if you don’t know it as coming from Beethoven 9, you most likely know “Ode to Joy.” Related to this, although I knew that “Ode to Joy” was from this work, and although I have heard recordings of the symphony, it was interesting to hear the famous melody in its original context. It is almost as if “Ode to Joy” has, in popular culture, lifted itself out of the confines of Symphony No. 9 to become its own entity.

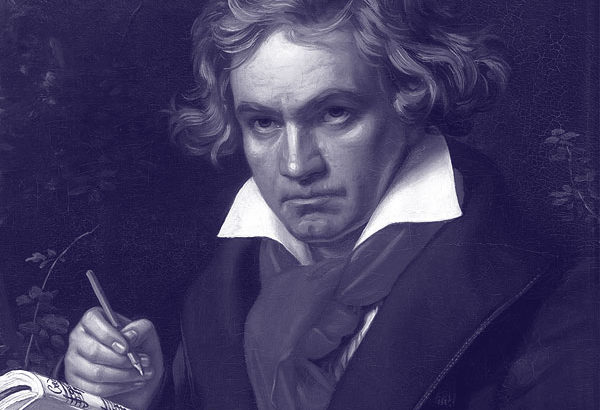

After the mildly disappointing Shostakovich, Beethoven’s famous work drew me and held my attention. It was awe-inspiring to fully process that Beethoven wrote his 9th symphony after he had gone entirely deaf. At the work’s May 1824 premiere in Vienna, he was unable to hear a single note. And yet, listening to the work, I realize that it is abundantly clear that the music was still very much alive in his mind’s ear. The beauty of the music cannot be captured in words on paper – it must be heard. In fact, Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 in D minor has become one of the most widely performed works in classical music, and it established itself as an impossibly high standard by which other composers’ 9th symphonies would be evaluated.