It is the special power of youth that one can transform a thousand times in the course of one lazy, Italian summer. That sense of self has not set yet. Perhaps it is a gift. A chance at change instead of stagnation. However, sometimes one simply exchanges the frustration of monotony for the near constant confusion of growing up into someone you don’t understand or maybe even like. It is this process of metamorphosis that 17 year old Elio (Timothée Chalamet) undergoes one summer break. Every year, his father, a renowned professor of archeology, invites older graduate students to live with the family in the small, country side Italian town. However, the summer of 1983 is immediately different. Oliver (Armie Hammer) is handsome, intelligent, and seems intent on disturbing all the regular rhythms and, perhaps even, the tedium that has built up one lazy summer, after lazy summer. He is forward and confident. He ends every conversation with a brisk “Later”, as if he will always return. At first, Elio handles his discomfort with Oliver with impertinence and distance. However, as the summer passes by, week by week, Elio is prompted to act upon his feelings, even if they may not fit what he may think of himself.

The glorious landscapes surrounding Elio aid both him and the audience as he embarks on this journey. The summer blooms brilliantly in a sumptuous, bountiful glory. Every tree in the family orchard is bursting with ripeness and every river runs cold and clear. Every swim is followed by a glass of freshly squeezed apricot juice. The Italian countryside begs to be explored, with its shady secret areas perfect for two lovers. It is a place that Elio is both intimately familiar with and yet, has never understood to its fullest extent. The eternal greenery and idyllic lifestyle that it encourages allows Elio and the viewer to imagine that perhaps summer will never end. He allows chances to repeatedly pass him by, even as his feelings for Oliver become stronger. But nature also acts as a prompting agent, urging Elio to live as vividly as it does.

This results in a film that is softer, more welcoming than other films that depict young, gay men coming-of-age. It seems impossible to compare Call Me by Your Name to yesteryear’s Best Picture, Moonlight, or even the more recent, Beach Rats; though they all may be simplistically reduced to the same genre. Elio does not encounter any opposition to his relationship with Oliver other than the values that he has internalized. Although same sex relationships were still largely forbidden in 1983, even those views seem muted as if the summer has allowed even reality to slip away with the flowing sunshine. Perhaps some will point to the lack of traditional, physical turmoil and see a drawback. However, it allows the movie to focus, instead, on deepening the relationship between Elio and Oliver, which it does with great success. Chalamet plays Elio’s yearning with a deep understanding, resulting in final scenes that are all the more devastating. His complex performance is complemented by Hammer’s perfectly.

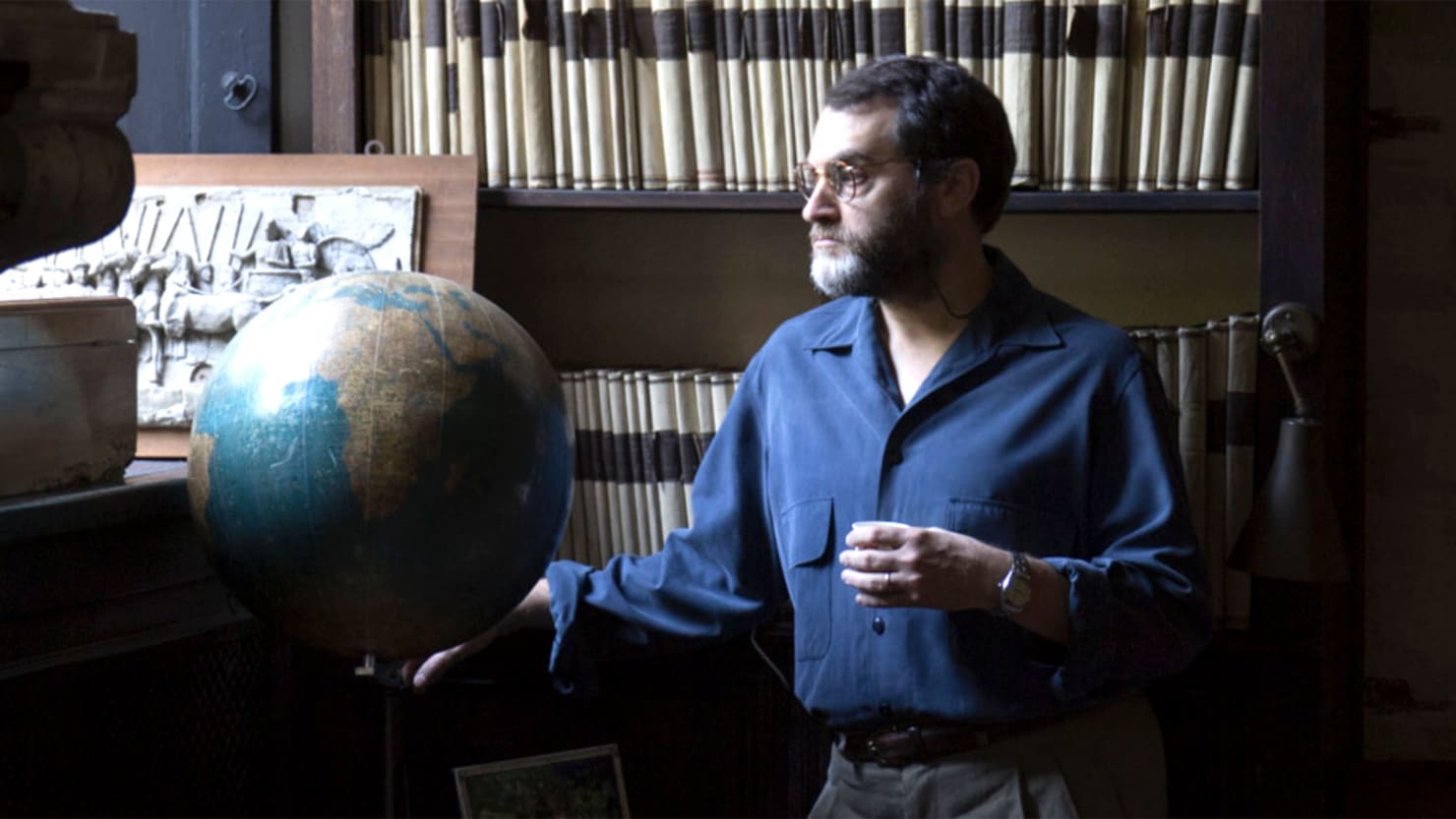

In addition to the two young men at the center, Elio’s parents (Michael Stuhlbarg and Amira Casar) bring a much needed contrast of experience and weariness. Time has already changed them irreparably. However, this feeling of being passed by is not expressed as cynicism or bitterness, but in support and hope for their son. Even time is not treated as an enemy, something to be raced against or contested. Life happens as a steady march forward and we simply change along with it. Elio and Oliver’s affectionate switching of names, the source of the movie’s title, is an acknowledgement of each other even as they are becoming other people. Perhaps we cannot remain youthful forever, but that promise of transformation, with its beauty and pain, is never lost.