Photos are provided by Peter Smith Photography

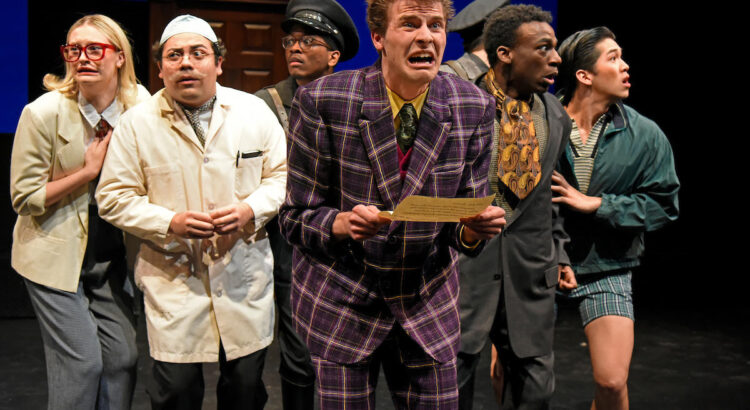

Directed by Malcolm Tulip from February 20-23 at the Arthur Miller Theatre, students from the School of Music, Theatre, and Dance performed Jeffrey Hatcher’s adaptation of the musical The Government Inspector by Nikolai Gogol. Though I was disappointed by the lack of singing and dancing in the production that typically characterizes a musical, it was still enjoyable to watch because of the goofy characters and comedic plot twists. In addition to the great acting, the outfits and set design further added to the immersive setting and made it a satisfying experience.

The plot takes place in a small Russian town in the 1830s. When the greedy and corrupt mayor, Anton Antonovich (played by Fabian Rihl), realizes that a government inspector has come for a visit, panic ensues as he and other high-ranking residents such as the judge, hospital director, and school principal attempt to win the inspector’s favor and cover up their misdeeds. However, their efforts are in vain due to mistaking the inspector for another visitor, Hlestakov, who relishes in their attention and money while continuing to hide his true identity as a depressed, low-level servant.

Though there was a short musical number introducing each character at the beginning, it was hard to keep track of them all because of the vast number of characters and their Russian names. Nevertheless, my favorite part of the musical was the characters. I loved the character dynamic between Hlestakov, played by Sam O’Neill, and his servant, Osip, played by Vanessa Dominguez. Hlestakov’s pathetic personality accompanied by Osip’s cold-hearted demeanor made them a hilarious duo. Similarly, I also loved watching the hospital director, played by Christine Chupailo, and the doctor, played by Gabriel Sanchez. Because the doctor didn’t speak the native language, the comedic timing of their messy dialogue made me laugh throughout the whole musical.

I particularly enjoyed watching the chaotic interactions within the mayor’s family. The mayor and his wife have a tumultuous relationship with each other and their daughter. However, Hlestakov’s arrival adds fuel to the chaos as he begins to get romantically involved with the mayor’s daughter, Marya Antonovna, and his wife, Anna Andreyevna. Student Nova Brown’s portrayal of Anna was especially amusing because of Anna’s bold flirting and her promiscuity. Furthermore, it was interesting to see how their indifferent daughter, played by Kristabel Kenta-Bibi, flirted with the mayor in comparison.

Overall, though I wish there was more music involved, I highly recommend seeing this show. The unique characters and satirical plot made the whole audience laugh, yet it was still able to highlight the consequences of human greed and stupidity.