Who would’ve thought New York City’s socialites’ children would have so much in common with Tolstoy’s tragedy set in Imperial Russia?

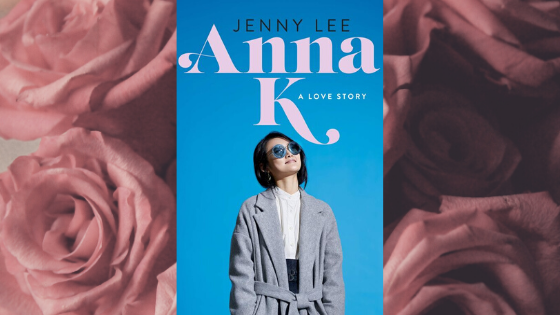

Jenny Lee, it seems. In her new book, released March 3rd, “Anna K”, TV writer Lee takes on the immense task of modernizing Leo Tolstoy’s “Anna Karenina” into a fresh, clever, and yes, frivolous, new novel. Welcome to the world of our Anna: daughter of a rich Korean businessman, Anna is NYC teen royalty. It doesn’t hurt that her boyfriend, Alexander, happens to be the well-respected “Greenwich OG”. Every private school, trust-fund teenager knows her for her charm, maturity, and her “endgame goals” beaux. Her life is perfect; until Alexia “Count” Vronsky steals her heart on the train from Greenwich into the city. With all eyes on her, Anna navigates a messy and uncensored love affair with the boy she truly loves in an attempt to go after what she wants, instead of what others prescribe for her.

It doesn’t help that the people closest to Anna seem to be trying to figure out their own romantic lives; Steven, Anna’s brother, unknowingly executes Anna’s initial run-in with Vronsky when he begs her to come home to soothe his enraged girlfriend Lolly who has just discovered Steven’s infidelity. Lolly’s younger sister, Kimmie, is unfortunately also head-over-heels for Vronsky, despite Steven’s friend and tutor, Dustin’s multiple attempts to win her affection. And we can’t forget Dustin’s brother Nicholas, newly released from rehab again, and his desire to find and pursue the woman of his dreams that he met in his rehab facility. The teenagers’ lives intertwine and untangle themselves again and again, with alarming speed and dexterity on the part of Mrs. Lee’s.

When I first started reading the novel, my roommates found a lot of joy in teasing me about my choice of genre. Anna K. fulfills a deeply guilty pleasure of mine. There’s just something about rich tweens and teens of NYC that makes great entertainment; “Gossip Girl”, “The Clique”, and now, “Anna K”. But it isn’t just its frivolity that makes it such a good read; Lee has a habit of sneaking in plain, poignant nuggets about the heart of humanity and love right next to what could be taken as the superficial. Lee places mundanity and phenomena next to each other to see if the audience can spot the difference; rather, in hopes that they can, but also perhaps because the two are not as different as we might generally interpret them to be. What is so lovely about Lee’s “Anna K” is how deeply and unapologetically she lets her young characters feel. It’s worth reminding any would-be readers of the first time they fell in love; how deeply we all fall and how catastrophic it is to our lives the first time we feel it with nothing else to compare it to!

In times like these, a light read about teenagers being well, teenagers, was a much-needed break. For those of you who have read Tolstoy’s novel, (SPOILER ALERT!) you know it doesn’t end well for the parties involved. Jenny Lee diverts from the original ending and fate of Anna for an ending, that while some may argue could be too “cliche”, I found to be very moving.

“[Love] gives us purpose and strength.” Hiding underneath the glitter and maybe one too many uses of the modern teenage colloquialisms, is a novel worth reading.