When first entering the exhibition, the words that immediately greet the viewer are “Please Take Off Your Shoes.” The title of this series reflects a custom common to many Asian households— a sign of respect for the host and a gesture of humility.

Strange You Never Knew marks artist and photographer Jarod Lew’s first solo exhibition, centering on the interplay between personal identity, generational stories, and a larger community. The idea of ‘knowing’ is not only Lew’s exploration of his identity but also asks the viewers to question the extent they know about others. With the title Please Take Off Your Shoes, Lew establishes the concept of exploring customs and stories rooted in his Asian heritage that is often obscured, inviting us into these invisible spaces of his community. The intimacy of these interior spaces and connections between humans serves as a contrast to the external perceptions of Asian American communities that tend to be surface-level and binary.

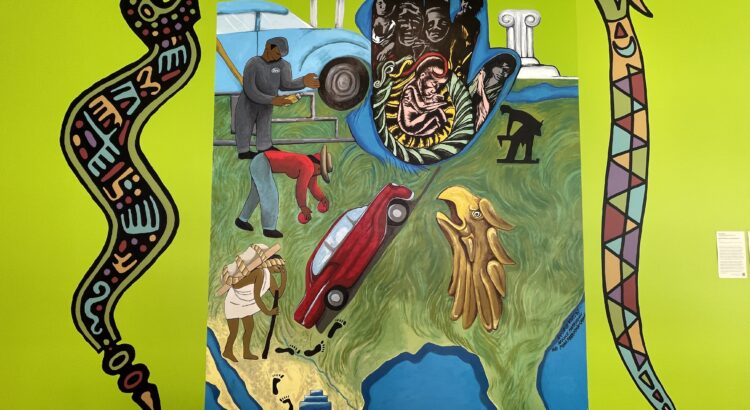

The exhibition consists of four sections— Please Take Off Your Shoes, In Between You and Your Shadow, Mimicry, and The New Challengers Strike Back—each examining the contrast between reality and perception. At times, Lew’s works are laced with humor and amusement. Try playing The New Challengers Strike Back where the goal is to beat up a car. Take a close look at the family-style slideshow in the living room and you’ll find that many of the photographs are of Lew’s face edited onto old images of white, suburban families. In one image, he’s a young boy at a birthday party, and in another, a doting wife. But there’s also a disturbing reality to other photos shown in the sequence: untouched photographs of midwestern communities hosting “Chinese Block Parties” featuring costume-like versions of traditional Asian attire. However, with these photographs in conversation, there’s a third element: genuineness. The other untouched photographs are the ones featuring the lived experiences of Asian Americans.

Genuineness pervades through the collections of works. At times, there’s a solemn beauty in the ways Lew captures his subjects, particularly his mother. This series was inspired by Lew discovering his mother had been engaged to Vincent Chin, a Chinese-American man who was beaten to death by two white automotive workers. Despite his mother’s wishes to be obscured in the photographs, Lew’s photographs preserve the stories that might have otherwise been lost in history. Vincent Chin is a name that reverberates in the Asian American narrative, but what of the other entangled stories?

I had the privilege of hearing both Lew and curator, Jennifer Friess, speak about the work, and hearing the stories behind the pieces accentuated my experience. I loved hearing about how shooting one photograph with his dad, the one where he sits wearing his post-officer uniform, made his dad cry. I remember Lew saying how his dad felt like he was wearing his old self again, this period of strength in his life. And how when Lew was departing for Yale, his father suddenly told him his grandfather was an enthusiastic photographer and showed him a box of his photographs, many of which appear in the exhibit.

This collection of photographs explores a necessary conversation about layers– the profound nuances within Asian American culture, the stories that trail between generations, and the histories that trickle into the present. Strange You Never Knew presents a powerful juxtaposition, true to the complex nature of identities emerging from different backgrounds. It is simultaneously humorous and playful, while also deeply reflective and personal. Most of all, it is welcoming in nature. While the perspectives in the exhibition may be something familiar or unfamiliar, the space is asking you to be open— to (metaphorically) take off your shoes. What awaits behind the door is an obscured hand, holding up a sign of love.

Strange You Never Knew: A Solo Exhibition by Jarod Lew is on view at UMMA through June 15th.