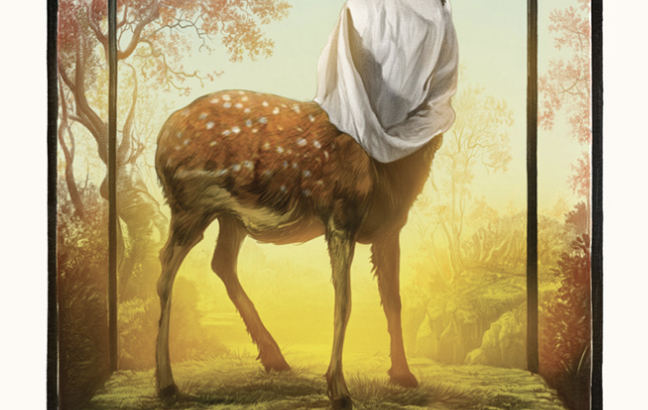

The Dig focuses on excavator Basil Brown (Ralph Fiennes) as he works on a site in Britain in 1939, owned by Edith Pretty (Carey Mulligan). The driving force of the film becomes the people who are brought to the site as they unearth an ancient artifact. We’re given glimpses into the lives of incredibly complex individuals, all who have their own internal and external struggles, and the only thing that has brought them all together is the dig site in the countryside.

Without giving too much away, I’d like to praise this movie as much as possible. From the beginning you can see how beautiful the film is, the sprawling landscapes of grass and trees, slightly obscured by morning mist or shrouded in a thick fog, the billowing clouds full of rain allowing only the most brilliant sunbeams to pass through, and quite frankly the dirt which looks so rich and velvety that you want to be there, in the film, just to dig your own hands into the gorgeous earth. I was blown away again and again by the scenery, and if nothing else, the film is worth the watch just to look at how beautiful nature can be. On top of that, the performances given by Mulligan and Fiennes are spectacular, and both are able to make the audience feel the way the characters are feeling, sometimes incredibly excited, other times extremely frustrated or full of existential sorrow.

One thing that I absolutely loved about the film was its spirituality and how it reminds us of our place in the universe. Each character has to wrestle with the idea that they are impermanent, that in a thousand years they will be forgotten, and all that will remain of them are some fragments of their possessions. We can see characters greedily cling to things that will preserve their past, which creates a dynamic between some upper class individuals and some of the workers on the site. Some of the highly educated want the glory associated with making such a momentous discovery, but those who actually did the work learn to let go. The characters that we sympathize with are those who realize that they are playing their part in an intergenerational saga. They aren’t meant to live forever as a famous name in history, they’re meant to live their lives and create a history for all of us to learn about.

I would encourage everyone to watch this movie. While it is admittedly quite Eurocentric (which I think is to be expected from a period piece based on a true story which took place in Britain), it delivers justice to hardworking people and critiques the upper class’s desire for self preservation. I think you would be hard pressed not to be sucked into the storyline within the first fifteen minutes of watching, and until you’re invested, the imagery will keep you more than satisfied. If you like to see how brilliant actors can be, watch Fiennes in the first opening scenes, listen to his accent and recognize that this is the same person who played Voldemort in the Harry Potter franchise (what a range!). Stay for Mulligan’s beautiful transformation as she struggles with letting go of her son, and the drama that develops when Lily James’ character is introduced at the halfway point of the film. The more I think of this movie, the more I realize how brilliant it really was, the direction, writing, sound design, and acting are all phenomenal. If I were to keep writing I’m sure I would give too much away, so I’ll contain myself and stop for now. If you can, please watch this movie, I’m sure you won’t regret it. 10/10

this group of films, and that doesn’t always feel completely right. In Life Overtakes Me especially, we observe several refugee children caught in the coma-like state of Resignation Syndrome; they are unaware at that moment of our watching them being taken care of like invalids. The cool, pretty sunlight comes through the window to highlight a delicate hand, the rising and falling of the chest filling with unconscious breath. Their parents are filmed almost as a performance of parenthood, having to ignore the cameras’s eye and the incredible pain of not knowing–their family’s refugee status, whether their child will regain consciousness, what would happen if they were deported. It feels like an intrusion, something I don’t deserve to see.

this group of films, and that doesn’t always feel completely right. In Life Overtakes Me especially, we observe several refugee children caught in the coma-like state of Resignation Syndrome; they are unaware at that moment of our watching them being taken care of like invalids. The cool, pretty sunlight comes through the window to highlight a delicate hand, the rising and falling of the chest filling with unconscious breath. Their parents are filmed almost as a performance of parenthood, having to ignore the cameras’s eye and the incredible pain of not knowing–their family’s refugee status, whether their child will regain consciousness, what would happen if they were deported. It feels like an intrusion, something I don’t deserve to see. offer anything but old-fashioned wisdom, always from a seated position. They have less

offer anything but old-fashioned wisdom, always from a seated position. They have less