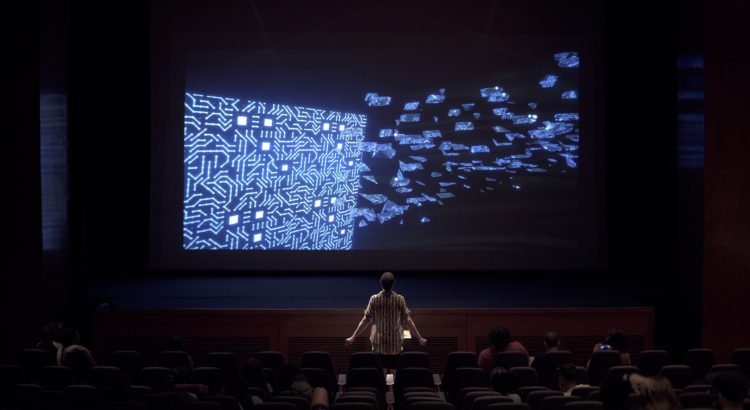

The lights dim, and a sense of communal excitement fills the air. This is asses.masses, a unique blend of performance art and interactive gaming that shows that UMS’s “No Safety Net series” is keen on shattering entertainment norms. Imagine embarking on an 8-12 hour journey through the whimsical yet poignant world of donkeys, alongside 60 of your newest friends—or better yet, fellow asses? It’s a spectacle that blurs the lines between audience and participant, reality and digital whimsy.

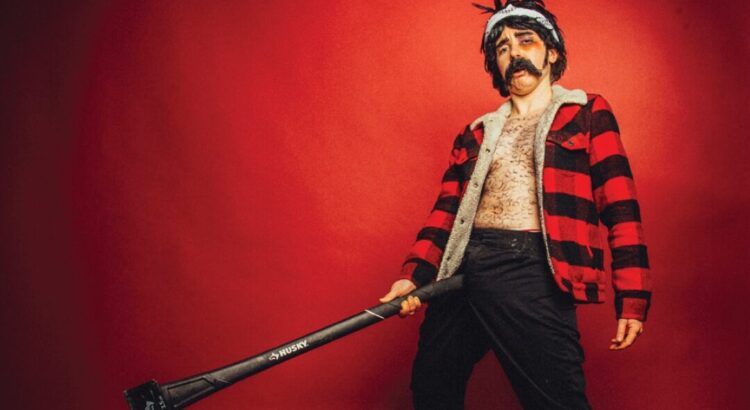

The night unfolds with this structure: bursts of gameplay, each lasting 1-2 hours, interspersed with 20-minute breaks full of delicious snacks to refuel the mind and ass (you were sitting for basically 12 hours straight). During each session, one, or multiple brave souls step into the spotlight to take control, leading us all through a donkey-laden adventure examining the complex themes of oppression amongst the masses (the asses).

And what a game it is! Without spoiling too much, let’s just say it takes you places: ass heaven (or perhaps hell), plots to save and slay donkeys, and interactions with the glinting eyes of ass gods. Our particular group, inventive as ever, decided to collectively voice these celestial beings, yielding echoes of laughter from the creators of asses.masses who were watching from a back corner. A spontaneous chorus, indeed and it seems we were pioneering uncharted ass communications.

What’s truly fascinating is the meta-narrative unfolding within and around this performance. It’s an interesting case study: you’re both an audience member of a performance and also a guinea pig who is trying the game for the first time. As we play, are we not testing the game itself? Watching each other’s reactions, it raises the question: how does our interpretation as audience members inform the art we’re immersed in? asses.masses challenges you to question whether passive observation equates to play; at the end of the evening, are you a gamer if you never held the controller?

Delving further, this unconventionally satirical journey through donkey society cleverly turns the mirror on governmental systems, ethics, and morality. Are we any different from the metaphorical asses, constrained by human societies’ dictates? In a delightfully strange twist, this absurdist narrative finds roots in eerily relevant social commentary.

If you ever get to see the show, bring friends along to share in the story and debate the ethical questions the story raises. But if you attend solo, then chances are you’ll leave with new friends, bonded over collective laughter, and some mutual existential musings about the plight of the ass.

asses.masses is a peculiar and transformational dive into interactive art. It encourages you to reflect upon and engage with the world, proving that games can be profound social experiments when left in the hooves of good company. Here, you’re not just along for the ride; you are part of an unpredictable, evolving story where the roles of ass and master blur. Hopefully, asses.masses will come to a city near you soon, and you can embark on a donkey-ful escapade.