At the beginning of this semester, as I worried about distribution requirements in my political science advisor’s office, I assured her that the Beginning Drawing class I had in my registration backpack had been put there on a whim. To my surprise, the advisor was delighted by my whim and urged me to keep the class on my schedule, eventually mysteriously manipulating something on her computer to help me fill a requirement. I was reminded of the nonchalance of my nuclear family’s emphasis on art – an art class, she felt, would obviously do me good.

She was right. Drawing is a constant tic for me, an activity that I can engage in almost unconsciously – so being forced to devote three hours, twice a week, to developing my skills and ideas has felt enormously cathartic. Although I wasn’t a ‘true’ beginner in that I could already draw fairly accurately, I hadn’t tried to really make progress in developing my abilities in a long time.

My favorite part of the class was the month long segment on figure drawing.

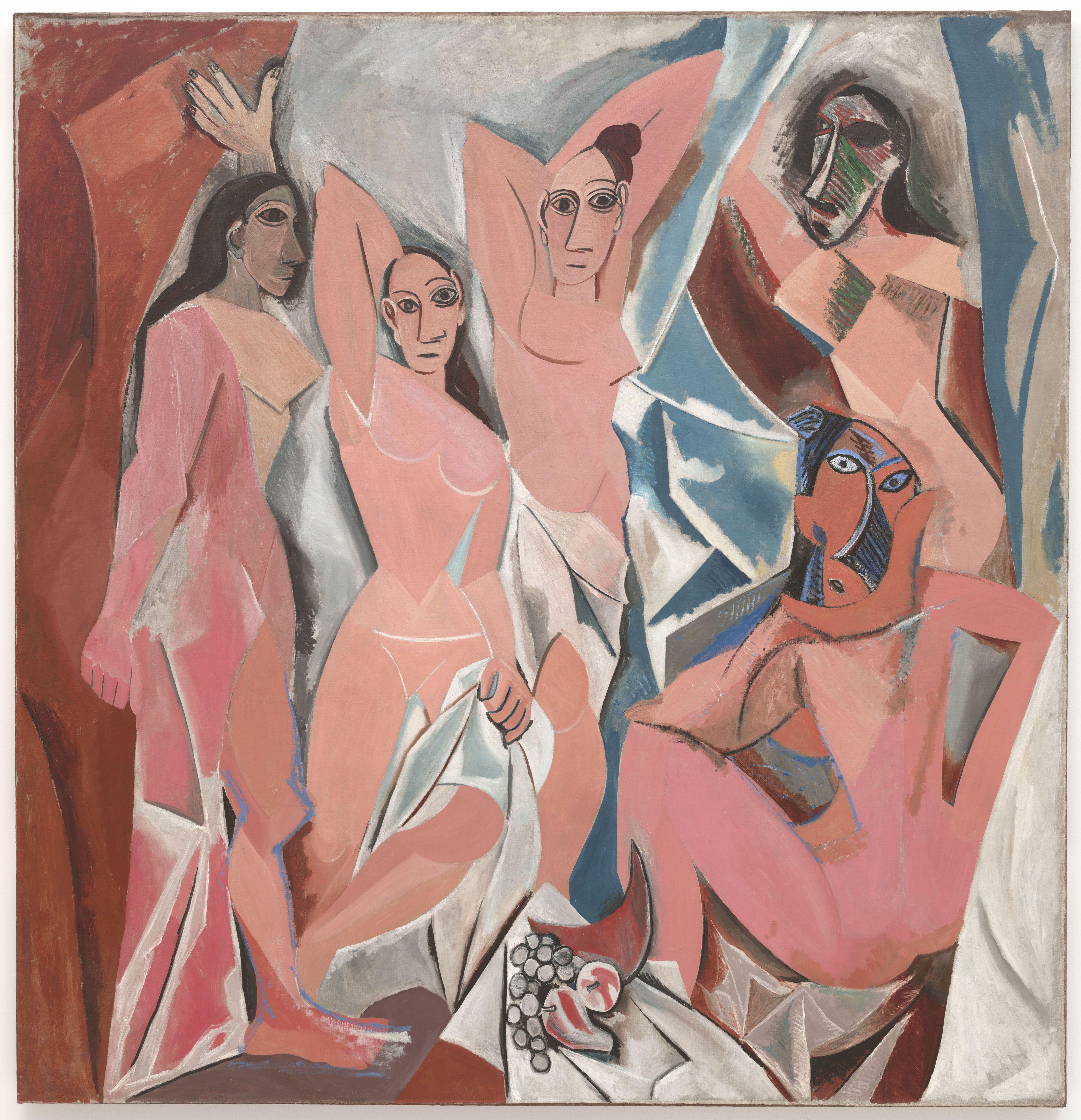

I love figure drawing for so many reasons, but mostly because it forces you let go of so many anxieties about the human form. In order to draw the hand, face or torso in front of you, you have to get rid of previous conceptions about what how those pieces of the body look, or ‘should’ look. Each individual’s body is an accumulation of their history that exhibits itself most obviously in scars and tattoos, but also in certain postures, masses of muscle, accumulations of fat, and tones of skin. This is why books that teach figure drawing tend to only impart generalizations – abstract instructions can only guide you to draw a perfect hand, an ideal profile, a measured bicep, pieces that sum up to a perfectly proportionate but fictional body. But when you draw from life, these rules (i.e., figures should be nine ‘heads’ tall, with shoulders three ‘heads’ across) are often confounded by perspective, space and the oddity of physical variation.

My favorite model was large, with rounded belly and breasts that the class delighted in suggesting with a few animated strokes of the pencil. Her mass filled up our papers (or dwelt a little off to the side, depending on whether I remembered the lessons on composition), and the smooth round shapes of her body lent themselves to broad gesture. The woman’s poses were the product of heavy, stolid efforts, accompanied by coughs, but her weight was consistently grandiose and powerful on our newsprint pages. As she doggedly raised her hands in the air for a five-minute pose, our drawings reflected how gravity appeared to be pulling her body downwards; as she sat or lay down we scribbled to describe the bows and bends of her protruding curves.

As the class progressed, our teacher suggested that we use our non-dominant hand to suggest the pose, or that we use multiple utensils bunched together in our fists. To my surprise, I loved my left-handed drawing, finding that my crudest attempts sometimes expressed the figure the most accurately. The gestural exercises that looked more like lines and less like humans captured something important about impermanence in their very lack of development: the human figure can’t be divorced from its vast potential for action and movement, not even if it holds very very still. The dead flowers that we contoured, the paper bags, the bottles and boxes and chairs – they had the potential to move but we were too unskilled to see or incorporate it. You can draw an acceptably ‘accurate’ still life without thinking about the potential motion of your fruit basket, but figure drawing somehow necessitates deeper perceptions of motion and mass.

And it’s much harder to form a smooth, developed drawing without losing some of the immediacy that comes in identification between the quick mark on the page and the impermanence of human motion or stillness. Some of my longer figure drawings turned out labored and disjointed because I felt like I had the time to slowly develop pieces of the body separately instead of making quick marks that suggested the figure – but without those initial, abstract descriptions, the pieces of the body failed to unite. When I consequently built my developed drawings on a foundation of gesture drawings, the unmeasured, instinctive marks gave my figures presence.

Within (or maybe above) these struggles, there’s something so amazing, so fascinating about drawing a human body – as my teacher commented, “it’s so hard to draw them, because they’re us.â€

It’s hard, but it’s also incredibly fulfilling. Embracing the human form’s oddities is strangely soothing to me, as I am no stranger to physical asymmetry. I was born with a cleft lip (I had my final repair four years ago), and I also have a permanently torn tendon in my right knee that has changed my posture and given me a much stronger, bigger left leg. Physically, these events have left only faded scars, a slight difference in the length of my legs, a minor irregularity in the shape of my nostrils. But to me, a lifetime of understanding self-worth as independent of beauty is intertwined with the scar tissue above my lip; my first encounter with age and permanence bound up in my uneven gait.

I used to consider it a kind of failure that I only wanted to draw people, that bodies engaged my artistic attention while I could only be bored by trees and buildings and tables and apples. But drawing people is essentially different. In class, our poorly drawn figures were sad little beings, slanted and un-souled and hilarious in their misery, but successful figures felt important beyond reason.

For our last self-portrait of the semester, we were only allowed to use our feet. Some people taped pencils to their socks or shoes, others held the pencil between their toes, some looked in the mirror, some didn’t bother. I held the pencil in my toes, and as my leg began to quiver from exhaustion I found that the shaking produced gentle, smooth shading. Slowly, I developed an oval. The drawing was meant to be a funny, loose exercise, and we spent most of the time laughing. But when a human face appeared, beneath my very foot – I can’t explain it, but I could have wept.