Brandon Graham has once again led me to another interesting find. This time, it is in the form of his multi-artist project called Island – a comic-magazine that hosts 3-4 stories that cover a similar theme, all written by different writers/artists. Prior to this, I never knew comic-magazines existed but to my surprise there were many illustrated magazines that had existed or are still running – one of which is called Heavy Metal (which incidentally has a new editor – Grant Morrison – a beloved and incredibly talented comic book writer).

My first foray into this format was undeniably pleasant for the magazine was constructed with great artistic and thematic eloquence. In total, there were five artists whose work was featured in the first issue. The first artist is Marian Churchland, a Vancouverite (and so beautifully captured by the her portrait – a white skinned goblin protecting its shiny stone), who drew the title pages, or rather, painted, with broad and bold brushstrokes of oil paint. However, she did not write any of the stories.

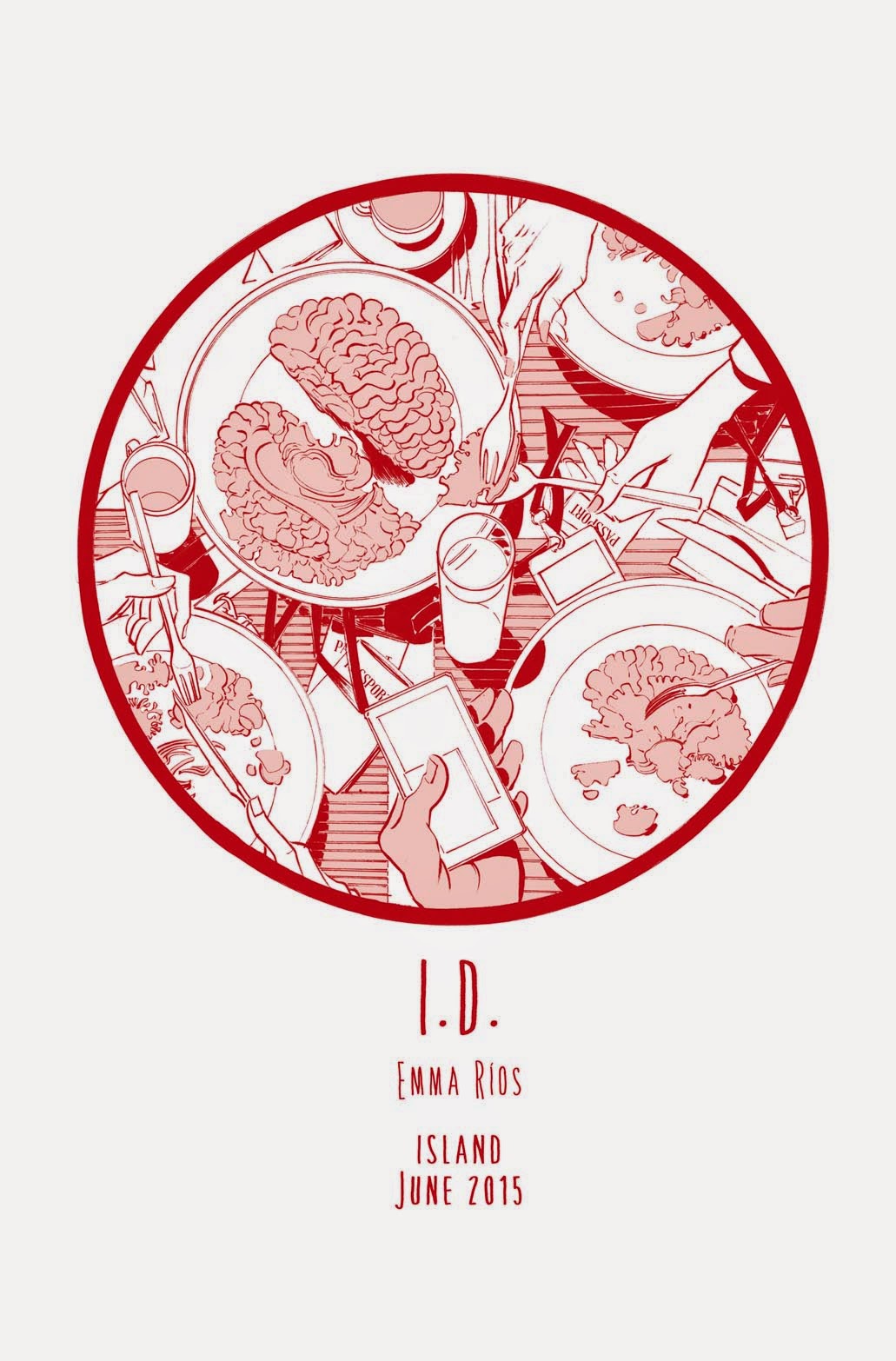

Then there is Emma Rios who wrote and drew the first story called I.D., which features three individuals who are unhappy about their bodies and wish to partake in a body transfer. The whole comic is done in red ink and although the basic story is tried and a little stale, the beautifully rendered background and swift lines keep the otherwise subdued tale, very energetic.

Afterwards there is an essay called Railbirds by Kelly Sue Deconnick, who, if you read comics, you might have heard of. She created, with Valentine De Landro, Bitch Planet (another title published by Image Comics). The essay is first and foremost, a tribute to the late Maggie Estep, with the undercurrent of whether or not Deconnick feels like she is a writer or not and how her interactions with Estep shaped her. The essay is fairly meta at times, and is quite conversational, but it is still interesting to see how someone worked through the question of: am I what I am?

Now we come to the comic by Brandon Graham called Multiple Warheads 2 (a continuation of Multiple Warheads which he did far prior to this project). Reading and viewing Graham’s work is always a treat and quite possibly the only time I allow myself to laugh at stupid puns (in the title spread, he has a sentence that says, “A pound of flesh but they won’t get a Graham.”). The story is about a boyfriend who is lounging about, in “vacation” mode, in a floating city while his girlfriend goes around doing smuggling work. Oh, also, did I forget to mention? The girlfriend smuggled a wolf penis and sewed it onto her boyfriend, making him half wolf. That is how biology works right? But in the midst of all this, the question of identity comes in again, as the boyfriend tries to find himself, as he considers how his girlfriend is doing so much work while he does nothing.

Graham’s work is, as is expected, visually dense. There is just so much to soak in. The backgrounds are littered with tiny details of tiny figures doing tiny things. Graffiti soaks the walls of shops that are cluttered with junk that are both of and not of this world. There are seemingly arbitrary numbers written on tree trunks and the backs of animal heads. But his density doesn’t create frustration; it creates wonder because of the breath of its creativeness. A whale café. How could you not want such a thing? He also has an interesting reaction panel, where there are two different outcomes based on what the female character, named Sexica, orders at the café. It is a visual inventiveness; one that is so aware of the possibilities of the exploration of space and narrative in a comic format, that is nothing short of astounding. Even his choice of color is beautiful. He uses muted tones that complement each other perfectly. And the smooth and clean lines and lack of tonal shading, gives it a Tintin vibe.

The final story is a skateboarding story by Ludroe called Dagger Proof Mummy (I can’t make this up – this title is amazing). It is a story about a mummy who gets attacked by cats with daggers and also about a girl who misses a skater named Dirk, a boy who can skate on walls and ceilings, who believes that once you stop “rehearsing for failure” you can break down all barriers and achieve greatness. Why wouldn’t the girl be convinced? He can skate on the ceiling! I won’t tell you how Dirk disappeared, in case you want to check out the magazine yourself.

By the end, the magazine does end in a grace note. Which is nice, but slightly cheesy. In the limited confines of a magazine, that is an accumulation of different artists’ work it is hard to know how to end it. But, if we consider the content outside of the individual stories, we can take into account the bookends that Graham created in this magazine.

In the very beginning, before the table of contents, the reader is treated to a very short comic featuring Brandon Graham’s actual head, spitting out the self-portrait of Graham, a yellow slug-like creature. It also features a godlike voice, commanding Graham to wake up, and not waste the creative freedoms he has been bestowed. Graham then considers creating a magazine, this magazine that features work from his fellow artist friends. Then at the end Graham ends with a quote from Federico Fellini.

“People ask me, ‘Why do you recreate Venice in a studio instead of using the real one.’ I’m always a bit surprised by such questions. I have to recreate it, because I have to put myself in it.”

He then goes on to muse about style, and space, and external versus internal influences on a story.

The ending bookend not only closes on a note that lets you forget about the cheesiness that happened earlier. But it also gets you thinking, not purely about identity, but the way in which an artist interacts with their medium. We have almost moved on, past the internalized struggle, and now towards finding yourself in something other than you.

I don’t know if this is an appropriate thing to mention given that the writer wrote in different fully formed personas, but it is still relevant, and nonetheless true. So, Fernando Pessoa once talked about the power of meditation, how “…the contemplative person, without ever leaving his village, will nevertheless have the whole universe at his disposal,” that, “One can sleep cosmically against a rock.” But eventually, when all our thoughts are but formulations of meditation, we yearn for life, a form of meditation that is absolved of intellect. Instead, drenched in the tactile richness of nature and life. We cannot live in ourselves forever.

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!