Postmodern art forms are often criticized as being too arbitrarily abstract, for being too cerebral, for being inaccessible to the general audience. Yet, the deconstruction and reconstruction of known forms is oftentimes a marvelous exercise in imagination. Dance, as any other medium, is not exempt. As part of the Brighton Festival this past May, the Trisha Brown Dance Company performed a set of four distinctive pieces.

The set opens with If you couldn’t see me, a ten-minute solo during which the dancer uses the entire stage but never once faces the audience. Meaning might be gleaned from movement alone, but the intentionality is so indistinct (does it exist? Is it meant to exist?) that it is difficult to formulate any sort of evaluation.

The final piece, For M.G.: The Movie, is less amoebeous but no less difficult to interpret. Several performers stand but never move a muscle for the entire half-hour duration. Another jogs the same circuitous path over and over, at varying speeds, for just as long. Yet others move into and out of the area, though without any discernible pattern. The entire thing is set to a soundtrack of distant booming sounds, occasionally discordant, a murmur of voices, and once, very jarringly, an empty can being kicked down the pavement. For a while, too, the stage is muffled in thick fog, obscuring some of the performers. If a friend had not beforehand hazarded to me that it might be a train pulling into the station, I may not have guessed. Yet this reimagining is surprisingly coherent (if only in retrospect), surprisingly logical, and despite that, still unpredictable.

Les Yeux et l’âme, set to Pygmalion, is perhaps the most accessible of the four, and the most familiar, employing the symmetry and fluid movement one has come to expect of dance. The performers play off of one another in a contemporary reimagining of Renaissance-to-Baroque choreography, employing a great deal more physical contact than dance of that evoked period, but still essentially recognizable.

Foray Forêt, however, is quite possibly the most notable not only in the way it defines the performance space, but in the way that it is possible to be aware of the way the performance space is defined. Much of the performance is carried out in silence. It is not entirely silent, of course; there is still the swish of fabric, the weight of landing on the floor, the turn of bare feet on polished wood. Then, at one point, music filters in home team win predictions, barely discernible, from offstage. It grows louder, then starts moving around from one side of the performance hall to the other (they’ve hired a local brass band to walk about outside).

It’s interesting, at this point, how uncomfortable people are with silence, and with things that are ambiguous in their role. The performance frame is traditionally clearly defined; there is a set timeframe and physical space and context in which what happens within that frame occurs as part of a cohesive text. This production manipulates these boundaries, reframing events that occur outside of it as peripheral, but within. Eliciting audience consciousness of what the production is playing with, is, I think, the point at which the performance becomes more understandable as a whole, is what in the end ties everything together.

Advertising creates clutter. Sides of highways are clustered with billboards waving at the thousands of drivers passing by each day. They are obstructive, bulky signs that stretch their wingspan over the surrounding trees to vie for attention. Advertisements coat the sides of websites, luring our eyes with distracting graphics and colors and mystery-inducing lines like “Language professors HATE him†and “1000th visitor! Click here to claim your free iPad†and “Meet sexy singles (like Ms. I-Swear-These-Aren’t-Implants-And-Every-User-Of-This-App-Looks-As-Sexy-As-I-Do).†They coat our cereal boxes, newspapers (for those old-timers out there), Facebook pages, daily commutes, etc. Each of these advertisements is in competition with each other, constantly swallowing massive amounts of revenue to become slightly better than their competitors. They pile up like layers of paint over a color-slut’s rented apartment. It is a desperate and futile, Sisyphean battle for our attention. As time moves on and we drown in their commercial rank, we become less willing to provide that attention.

Advertising creates clutter. Sides of highways are clustered with billboards waving at the thousands of drivers passing by each day. They are obstructive, bulky signs that stretch their wingspan over the surrounding trees to vie for attention. Advertisements coat the sides of websites, luring our eyes with distracting graphics and colors and mystery-inducing lines like “Language professors HATE him†and “1000th visitor! Click here to claim your free iPad†and “Meet sexy singles (like Ms. I-Swear-These-Aren’t-Implants-And-Every-User-Of-This-App-Looks-As-Sexy-As-I-Do).†They coat our cereal boxes, newspapers (for those old-timers out there), Facebook pages, daily commutes, etc. Each of these advertisements is in competition with each other, constantly swallowing massive amounts of revenue to become slightly better than their competitors. They pile up like layers of paint over a color-slut’s rented apartment. It is a desperate and futile, Sisyphean battle for our attention. As time moves on and we drown in their commercial rank, we become less willing to provide that attention. Like seriously, TMI. We don’t want any more pointless grains of information. We don’t want to be manipulated into spending our money a certain way. We don’t want to be

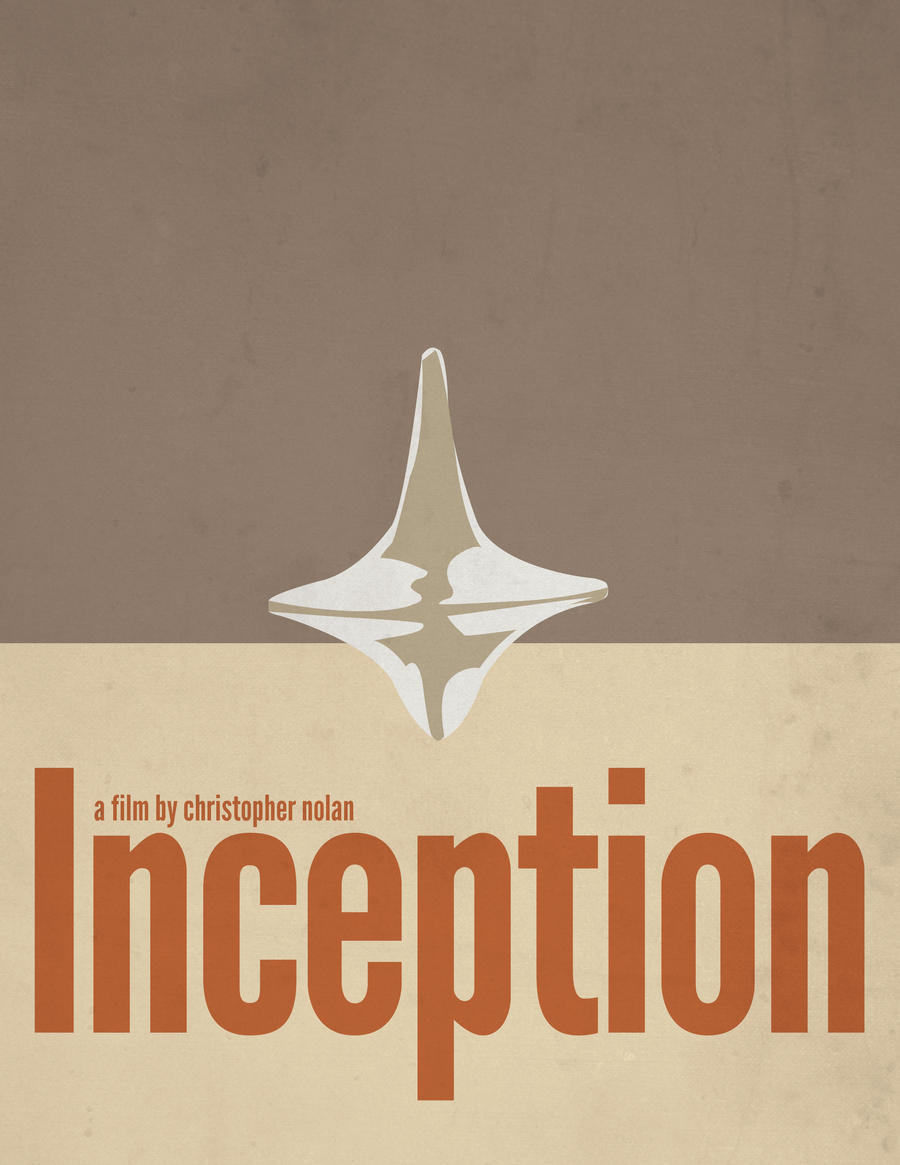

Like seriously, TMI. We don’t want any more pointless grains of information. We don’t want to be manipulated into spending our money a certain way. We don’t want to be  A new movement that seems to have been gaining footing in pop culture over the last few years is the design of minimalist posters. Movies and books and famous characters have been stripped down to iconic details and artistically portrayed in the simplest forms. Superheroes may be reduced to the shape of their mask. Great scientists may be trimmed down to a few crossed lines. Epic films may only contain a single object. This form of stripping down is art in its purest form. Like the naked body, untouched by makeup or product, not hidden behind a layer of cloth, shows the true beauty. It is fruit, freshly plucked from the tree. Unadorned, it is the most delectable.

A new movement that seems to have been gaining footing in pop culture over the last few years is the design of minimalist posters. Movies and books and famous characters have been stripped down to iconic details and artistically portrayed in the simplest forms. Superheroes may be reduced to the shape of their mask. Great scientists may be trimmed down to a few crossed lines. Epic films may only contain a single object. This form of stripping down is art in its purest form. Like the naked body, untouched by makeup or product, not hidden behind a layer of cloth, shows the true beauty. It is fruit, freshly plucked from the tree. Unadorned, it is the most delectable. Plus, these posters embody something that advertisements never can. A wholesomeness. A genuine appreciation for what the topic stands for. They are not trying to sway viewers into buying some product or conforming to some new trend, but simply provide something we can appreciate. It is simplifying an artifact of pop culture that would otherwise be overly bedazzled in manipulative tricks. The art of making the complicated simple is the threshold of beauty. Our attraction is sparked in the simplest of ways. We don’t like clutter, so show us the fruit.

Plus, these posters embody something that advertisements never can. A wholesomeness. A genuine appreciation for what the topic stands for. They are not trying to sway viewers into buying some product or conforming to some new trend, but simply provide something we can appreciate. It is simplifying an artifact of pop culture that would otherwise be overly bedazzled in manipulative tricks. The art of making the complicated simple is the threshold of beauty. Our attraction is sparked in the simplest of ways. We don’t like clutter, so show us the fruit. This is Misleading

This is Misleading This is more accurate

This is more accurate