Despite a general acceptance of non-heterosexuality in modern media and society, queer characters are often placed in plots that are only focused on their ~journey of self-discovery~ or in supporting roles that stereotype and tokenize them. So often, they are reduced to their sexuality, communicating to the audience that this is the only part of their identity worth mentioning. Surely, it’s important to feature queer characters in media, but every story can’t only be about their struggles with unaccepting parents/religion/schoolmates/colleagues/whatever. We normalize queerness by incorporating it in media in a wide variety of ways.

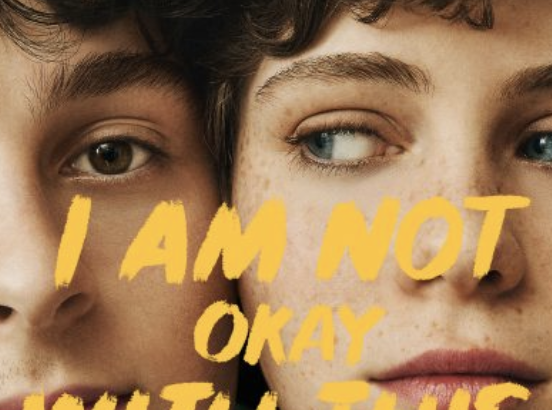

So I was overjoyed to find that this series has a queer star who spends some time recognizing her sexuality, but is primarily preoccupied with a full storyline about her new mind powers and their possible connection to her late father.

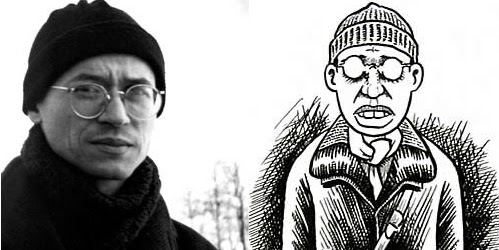

Based on Charles Forsman’s comic of the same name, the series honors the original work, often taking sections of text into the script verbatim. I’d say that the writers could have taken some more liberty with dialogue, which could be lacking in originality sometimes. The media move from comic to television necessitates this; while comics with a minimalist art style depend on fast-paced conversation between characters to drive the story, live action dialogue is generally less important. Makers of television are freer to insert some more artistry in angles, lighting, wardrobe, delivery and content of lines.

A lot of talented people worked on the series: people responsible for Stranger Things and The End of the F***ing World, actors who starred in the updated version of IT. But if I know anything about logical principles, I know that past performance is not indicative of future results. I Am Not Okay With This is an unfortunate piece of evidence for that rule.

Along with the lacking dialogue, there were too many illusions to late 20th century pop culture, like The Breakfast Club-esque episode and the constant Carrie references. While I understand the the entire plot is literally another reboot of that classic Stephen King story, they could have strayed a little farther, style-wise. The spring fling dress is even similar to the one Sissy Spacek wears in the original movie, pale pink satin with spaghetti straps. She does the whole walking home from the dance in the middle of the road covered in blood thing, and she doesn’t add to it. If you’re going to pull so directly from classic works, you need to do something that differentiates it from the original, pushing it farther, bringing into modern times so it can be understood within current social politics.

It’s sad when the arc of creativity starts to decline for previously awed artists. This feels like the desperate reaction to writer’s block that should’ve been given some more time to simmer. Still, most folks are wont to continuously seek out media that gives them the same kind of satisfaction as they’ve experienced in the past. So, at this psychological level, the series does a great job. Though that feels like some kind of exploitation, it fills a demand. I’m not sure I’d call it art, though.