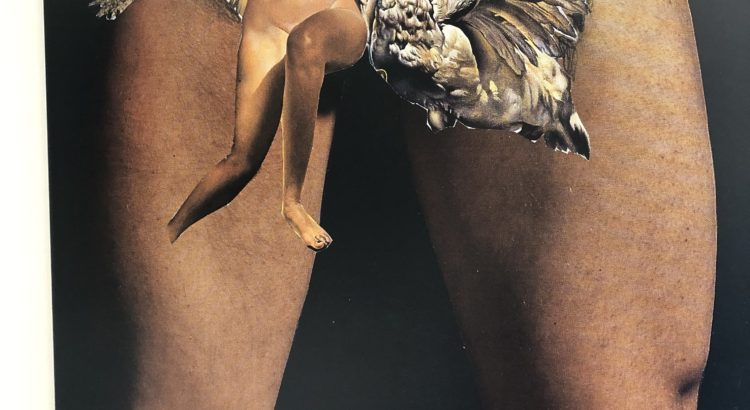

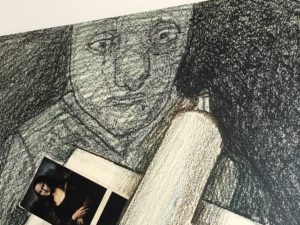

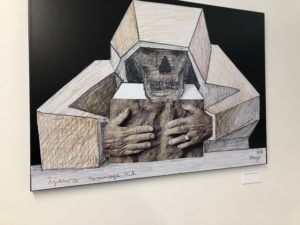

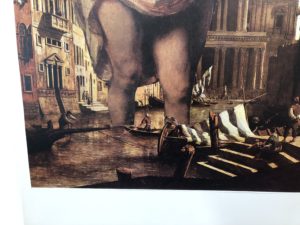

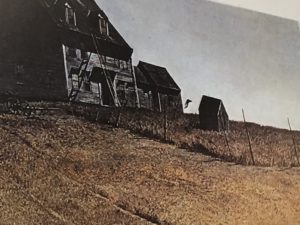

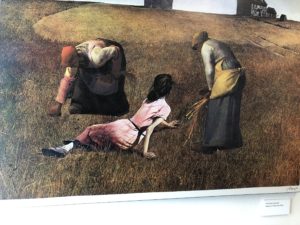

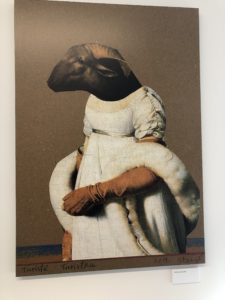

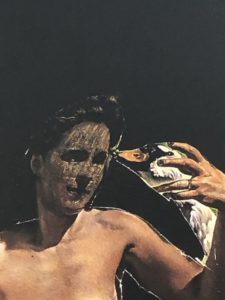

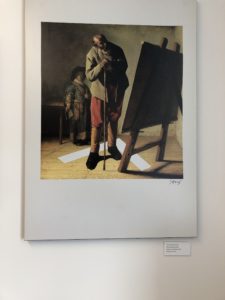

Before you read on, take a close look at Stasys Eidrigevičius’ pieces. Notice what you will about his placement of objects in relation to one another, the emphasis on odd shadows, all the shapes and angles involved. Regard each separately, trying not to immediately put any of the images together:

What can I say about these works? I was so befuddled by each one, torn by the wanting to fixate on the alarming details and the knowing that taking it as a conglomeration is the meaning of collage.

All I could do was be overwhelmed by slight curves in the edges of the pieces and the uncomfortably forced eye contact between figures. The expressions on characters’ faces ranged from haunting to somber to desperate to dazzled to sadistic to sly. I wasn’t sure what to make of the positions Eidrigevičius puts these persons into. It feels like each piece has an element of force that I find unsettling. Hands grip, eyes pierce, feet trample. Everything seemed too jarring to work together as cohesively as I expected it should.

Eidrigevičius further adds chaos to his work through additions made by his own hand. He deals in scribbled shading and blocky figures, asymmetrical faces and indiscernible expressions. I was so distraught by the time I’d spent ten minutes in the room with the artwork that I could hardly see straight. An unfortunately poetic, single tear rolled down my flustered cheek. Seconds after the only other people entered, I had to hightail it out of there, but not before I heard their first impressions (“Very symbolic,” says the man with an angular European accent. “Hm,” replies the woman, curtly. “I’ve been trying to figure out what the symbolism is,” he continues, illuminating nothing).

I don’t know that I could pick out any one symbol that persists throughout the pieces, or even a general grouping of motifs. Everything seems literal to a point of discomfort (mine), but I suppose there was a similar line of thinking throughout the collection. Something in each piece is being trapped, maybe not by the specific creature in the image, but by something. Entrapment could be a metaphor for something else, or it could represent nothing else but itself. Perhaps the artist is feeling constricted by the world’s narrow view of what art should be. Maybe he is reflecting on a home country whose practices of censorship are too harsh for goodness to grow.

Or maybe, as I always prefer to believe, Eidrigevičius strives only to challenge the limits of his viewers’ and his own thinking by combining unrelated objects and ideas. His mind knows few borders between things, preferring to string a doodle onto the end of everything. He sees shadows that might not be there, connections bridged between the physical and the emotional. There may or may not be anything much deeper than artwork that wishes to be fully open to interpretation.

If you’re interested in seeing Eidrigevičius’ work in the flesh, I urge you to visit Weiser Hall’s International Institute Gallery, room 547. The exhibit will be up until the end of November.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/57822053/56ab5c101f00005000216e6d.0.jpeg)