Last weekend I actually got off of the Youmacon Artist Alley waitlist extremely last-minute (like, getting off on Friday of the Friday to Sunday convention weekend last-minute), so I tabled for all three days with the stock I had prepared for Motor City Comic Con and actually surpassed all of my previous sales records and expectations for convention selling! If you’ve been following me for a while, you’ll know that I split a table at last year’s Youmacon with a friend as one of my first convention selling experiences. This year I had a whole table to myself, and I think my art and display have seen massive improvements since then, as you can see in my table display pictured below:

My convention table setup this year, though I did rearrange some of the prints on my photostand later that weekend

Considering how much better my bank account looks now, I actually want to talk about a few different types of income streams that working artists rely upon to make a living, pay bills, keep their art business going, or sometimes just to have “fun money”. Typically artists will rely on multiple income streams/sources to minimize volatility from surges and recessions in the demand for certain types of art services.

Commissions

Getting other people to pay for you to draw them custom artwork is a pretty common way to make money as an artist. If your skills are valuable enough and you get your name out there one way or another, clients will be willing to pay a pretty penny for your services. Typical personal commissions cost anywhere from sub-100 dollars to hundreds of dollars, with some clients potentially being willing to pay over a thousand or more for your artwork if you’re in the top echelon of commission artists.

Commercial commissions (e.g. working as a contractor) pay much better than personal commissions and typically pay several thousand dollars per piece, but they’re also much harder to secure with higher skill and networking requirements to get your foot in the door.

Online Store

A lot of artists run an online store, whether they’re selling digital products, their mass-manufactured products, or even original artworks. If a lot of people from around the country or world want to purchase your products, this can be a decently regular and significant income source. However, there’s a lot of necessary know-how to actually market and run and online store, and actually fulfilling orders can become very time-consuming (I literally just spent 2 hours the other day packing orders). While I don’t focus as much on my online store as I do on other income sources, my online store has taken off enough to the point that it now constitutes a decent part of my income in between commissions and conventions.

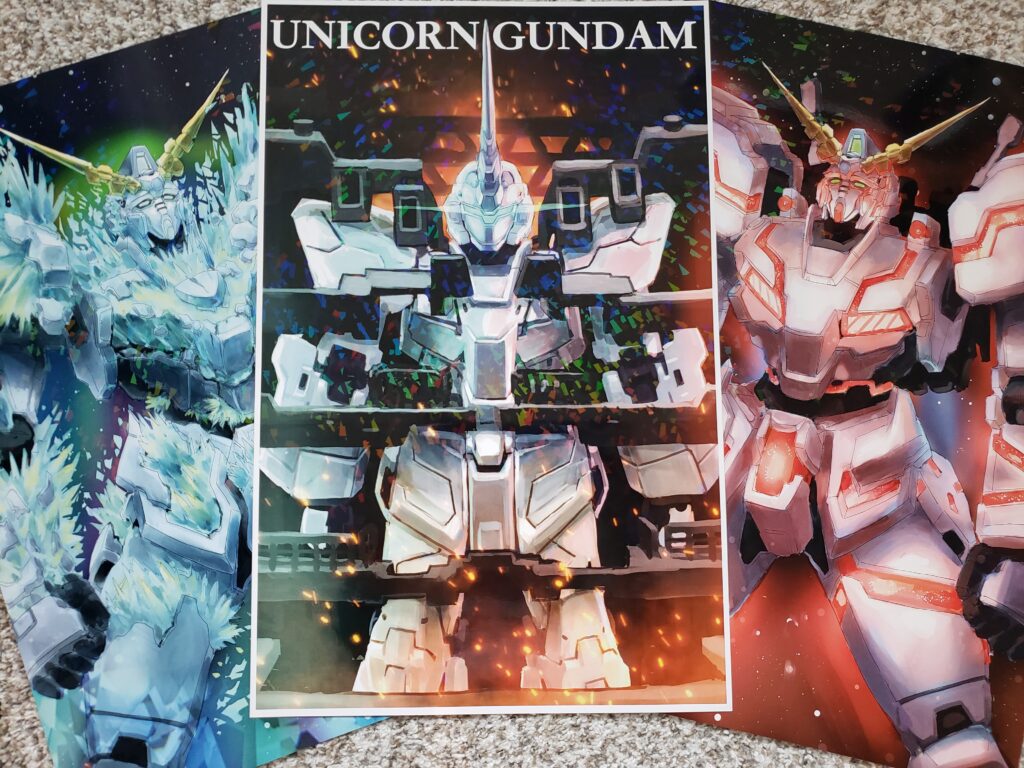

Conventions (mass-produced products)

I’ve definitely already discussed conventions a few times before on this column, but they’re worth mentioning again if the type of art you create is geared toward pop-culture fans or simply can be sold in a cheaper mass-manufactured form. Just like with most types of online stores, the money you make per sale isn’t that much, but getting a lot of purchases in a single weekend can add up pretty fast and lead to significant take-home income relative to the amount of hours you spent selling. However, the cost and time investment involved in paying for table space/travel/merchandise is also pretty significant, and most people only break even or barely make a profit after expenses.

Fine Art events (originals)

I don’t know as much about this type of income since I’ve never tried to make money through this income stream, but I’ve attended a bunch and have a few acquaintances who are working to break into this sphere. Just as online stores and convention selling involve combining business acumen with an attractive display and good art to make people believe in the worth of your work, fine art events involve showing off your impressive one-of-a-kind creations and selling them for large sums of money similar to or larger than the amount of money you’d charge for custom commissions (in the hundreds or thousands of dollars). They also have a high initial start-up cost and most people don’t actually make a living off of doing this (which is true for pretty much all of the income streams here). Really, the main difference is the type of audience you have to woo and what kinds of signifiers (e.g. connections, presentation, the quality of your artwork) they recognize as determining the value of paying for your work. As for what those are, you’re better off asking someone else besides me, sorry.

Patreon/Subscriptions

I also don’t know as much about this type of income source, but it’s the closest thing that many independent artists have to a reliable income source. Usually this takes the form of digital goodies (work-in-progress pics, high-quality final pics, a monthly poll to choose an art idea to draw, etc.), but some artists run monthly enamel pin/sticker/charm/etc. subscription services where they mail out a merch package to their subscribers on a regular basis. The per-patron revenue oftentimes isn’t very high because of the expectation that subscription services that provide the same services to everyone who use them shouldn’t be too expensive, but the artists who secure a large and devoted paying following can make a respectable income off of monthly subscription money.

Full-time work

The dream for many artists is to find stable, full-time work with a company so that they can get typical employment benefits (including retirement and health insurance) and not have to juggle several different hustles at the same time to get by. However, full-time employees are expensive for companies to pay for, so in the age of increasing cost-cutting, outsourcing, and automation there’s fewer and fewer full-time jobs available — and the ones that do still exist are oftentimes higher level jobs which require years of experience at other full-time art jobs. Basically, more and more artists in the future will have to rely on some of the other income sources described above.

Of course, these are all very broad descriptions, and there’s many much more specific ways to profit off of these types of income streams, but I hope these descriptions are helpful enough as a way to help you get thinking about how you want to get money in exchange for the value of your artistic labor!

Also, I’ll be tabling in the Artist Alley at Motor City Comic Con this weekend starting from the time that this post goes live, so I’ll make a mention of how I did at my first comic con tabling experience in next week’s column!