I loved this movie, especially as I wandered into the screening room without thinking that I would.

Ploy follows the addition of a stranger (the titular character) into the lives of two troubled people making the mistake of languidly existing in a deeply flawed marriage, and doing nothing about it. She looks far younger than the nearly 19 years she claims to have lived; her doe-eyed youthfulness plays into the strength of the chaos she innocently unleashes. While unsettling given her childlike features, she holds a clear sexuality that serves to beckon forward the evil already within the couple’s complicated relationship.

Although the director fiercely guards his definition of the movie as a simple, commercial one (and certainly not of the art house variety, as many critics and fans have claimed), the entire time I was seeing metaphors in everything, appreciating his sense of aesthetics; the subtleties of object placement and camera angles and color and slight expression changes on the characters’ faces.

The intense scene with Dang trying to escape her armed captor at the abandoned warehouse was chillingly beautiful despite the typical artlessness of violence. The wind rustling through the ripped, translucent plastic created a feeling of being inside a kind of dust storm, the panic of the events coalescing with an uncertainty of direction and decreased visibility.

The hotel’s hallways were strikingly bare, though the inside of the rooms are lavishly modern suites with full kitchens and enormous beds. The bar has a lonely, electric feeling to it, part old-timey diner and part futuristic hangout. The lobby feels more like an empty airport, the back of the taxi a warm, wet cavern.

Some things were left mismatched, maybe as a nod to how the paranoid, lonely mind creates frantic stories when reality gives out less information than needed. The purpose of the thievery of the suit jacket and pants is never revealed, nor is the question of whether the hot-blooded romance between the maid and bartender is real or a dream of Ploy’s. Also, the identity of the boy she’s with in the beginning is never revealed. Rather than viewing these things as plot holes, I recognized their role in enriching the jarring feeling of love lost Ratanaruang was trying to create.

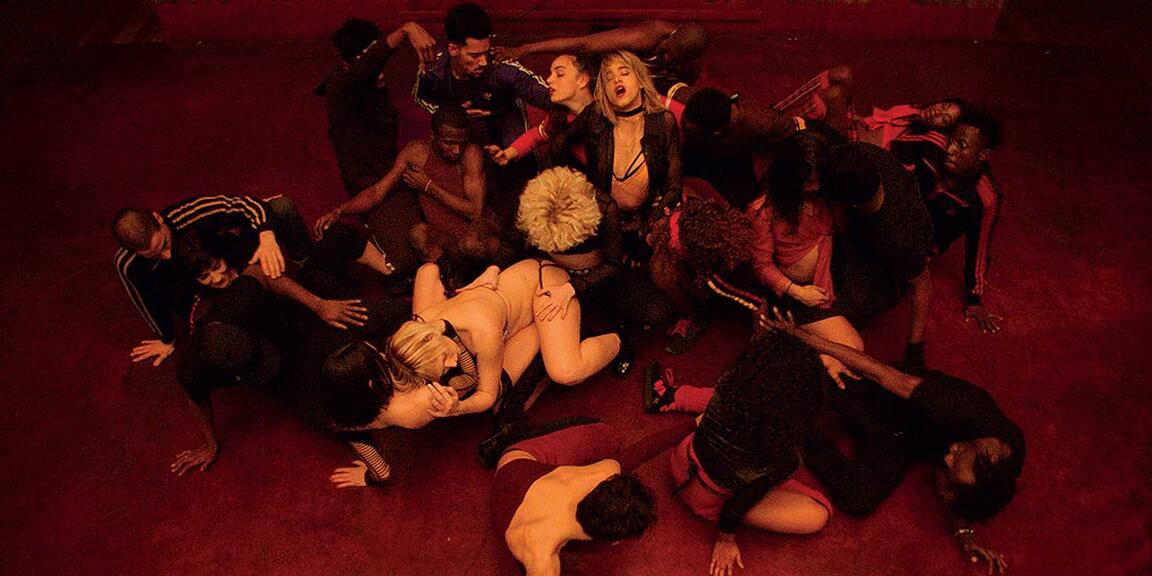

But whether or not the romance between the two young lovers was a fabrication of Ploy’s imagination is unimportant. Instead its significance lies in the sad hope they and we all have in new love. Placed next to (in all its beautifully erotic glory) the failing marriage Dang and Wit share, it both depresses and envigorates, causing us to question how we unfailingly fall into the ecstacy of novelty despite our knowledge that it may eventually end, or at least shift into something far less enticing.

It’s hard to say whether to take Ploy as a gift or an evilness. The way the movie ends, it seems we are supposed to conclude the former, but I didn’t feel satisfied with that. Her presence does exacerbate the couple’s arguments, which eventually leads to uncharacteristically bold actions that end up bringing the two closer together, but the pain she brings about is almost glazed over in this. Dang is the victim of violent sexual assault and (we are led to assume) she ends up killing her captor, but after the fact this is not mentioned, the enormous range of emotions created remaining unexplored and unexpressed. Having an ending where the couple comes back together, seeming to even happily glow in the backseat of the taxi, seems again a direct ignorance of the lesson in communication Ploy was meant to teach. But then, maybe this was the film’s vision, to show the cyclical nature of apathy to anger turning into self-fooling false happiness. Or maybe it’s meant as a truly happy ending, in which honesty is less important than intentionally appreciating one’s partner.

If you haven’t seen this movie yet, I would strongly urge you to watch it.