A conundrum I’ve always tried to elucidate is whether an acoustic/folk album comprised of songs that essentially sound the same is a display of the artist’s ability to produce specific, cohesive and polished music, or whether it should be seen as a disability of the artist to diversify their creativity. I’ve struggled with this quandary with practically every Jack Johnson record, the Avett Brothers, a lot of John Mayer’s music and (although I don’t at all agree with this) I’ve heard Bon Iver be criticized for it as well. I am presented with this problem most recently by the Mumford & Sons release Babel, which is their second studio album. In my opinion, both of Bon Iver’s albums are similar, but not identical in sound; their variances are easily noticeable due to the array of instruments used and definitive stylistic deviations throughout the albums. Even Jack Johnson records incorporate different methods to the point where I can readily distinguish between the individual tracks. Try as I might, though, I cannot say the same for Babel.

Although it is easy to identify one or two of the songs without looking at the track list, the majority of this album sounds almost identical. It seems as though the chords and rhythms progress without alteration throughout the entire piece. This happens not because the band fails to utilize a wide array of instruments- in any given song there can be a combination of guitar, drums, mandolin, keyboard, accordion, dobro and, of course, banjo- but because they use all of these instruments in practically every song. With the exception of “Babel,†“Ghosts That We Knew†and “Hopeless Wanderer,†it took me a substantial amount of full listens to be able to differentiate between the tracks; they simply all sound the same.

The important question lies in the significance of this resemblance. Does this mean that Babel is a weak album? Or that Mumford & Sons are only capable of creating one type of music? In my opinion, the answer is definitely no to the first question, and for the most part no to the second. Babel is undeniably an impressive record; despite this flaw the songs all still sound marvelous. In an “If it ain’t broke don’t fix it†mentality, I don’t mind listening to songs that sound similar as long as I still enjoy listening to them. I particularly appreciate this music while studying as it drowns out any disruptive, outside noise but changes so minimally that it does not distract my focus away from the work. As to the second question, I think it is important to clarify that although Mumford & Sons have only ever produced stylistically similar music, this does not mean they are not talented artists or that they are only capable of composing a single genre of music. It just means they know what they are good at and have become extremely successful within that category. Granted, it is more impressive when artists show some sort of growth and development, but as this is only the band’s second album I think there is still potential for this maturation. In any case, as long as it continues to sound as fantastic as this piece, I’ll keep listening to anything they produce. The magic of this music is that it never gets old- I will always have a hunger for some soothing folk, bluegrassy tunes to accompany me in the library.

Advertising creates clutter. Sides of highways are clustered with billboards waving at the thousands of drivers passing by each day. They are obstructive, bulky signs that stretch their wingspan over the surrounding trees to vie for attention. Advertisements coat the sides of websites, luring our eyes with distracting graphics and colors and mystery-inducing lines like “Language professors HATE him†and “1000th visitor! Click here to claim your free iPad†and “Meet sexy singles (like Ms. I-Swear-These-Aren’t-Implants-And-Every-User-Of-This-App-Looks-As-Sexy-As-I-Do).†They coat our cereal boxes, newspapers (for those old-timers out there), Facebook pages, daily commutes, etc. Each of these advertisements is in competition with each other, constantly swallowing massive amounts of revenue to become slightly better than their competitors. They pile up like layers of paint over a color-slut’s rented apartment. It is a desperate and futile, Sisyphean battle for our attention. As time moves on and we drown in their commercial rank, we become less willing to provide that attention.

Advertising creates clutter. Sides of highways are clustered with billboards waving at the thousands of drivers passing by each day. They are obstructive, bulky signs that stretch their wingspan over the surrounding trees to vie for attention. Advertisements coat the sides of websites, luring our eyes with distracting graphics and colors and mystery-inducing lines like “Language professors HATE him†and “1000th visitor! Click here to claim your free iPad†and “Meet sexy singles (like Ms. I-Swear-These-Aren’t-Implants-And-Every-User-Of-This-App-Looks-As-Sexy-As-I-Do).†They coat our cereal boxes, newspapers (for those old-timers out there), Facebook pages, daily commutes, etc. Each of these advertisements is in competition with each other, constantly swallowing massive amounts of revenue to become slightly better than their competitors. They pile up like layers of paint over a color-slut’s rented apartment. It is a desperate and futile, Sisyphean battle for our attention. As time moves on and we drown in their commercial rank, we become less willing to provide that attention. Like seriously, TMI. We don’t want any more pointless grains of information. We don’t want to be manipulated into spending our money a certain way. We don’t want to be

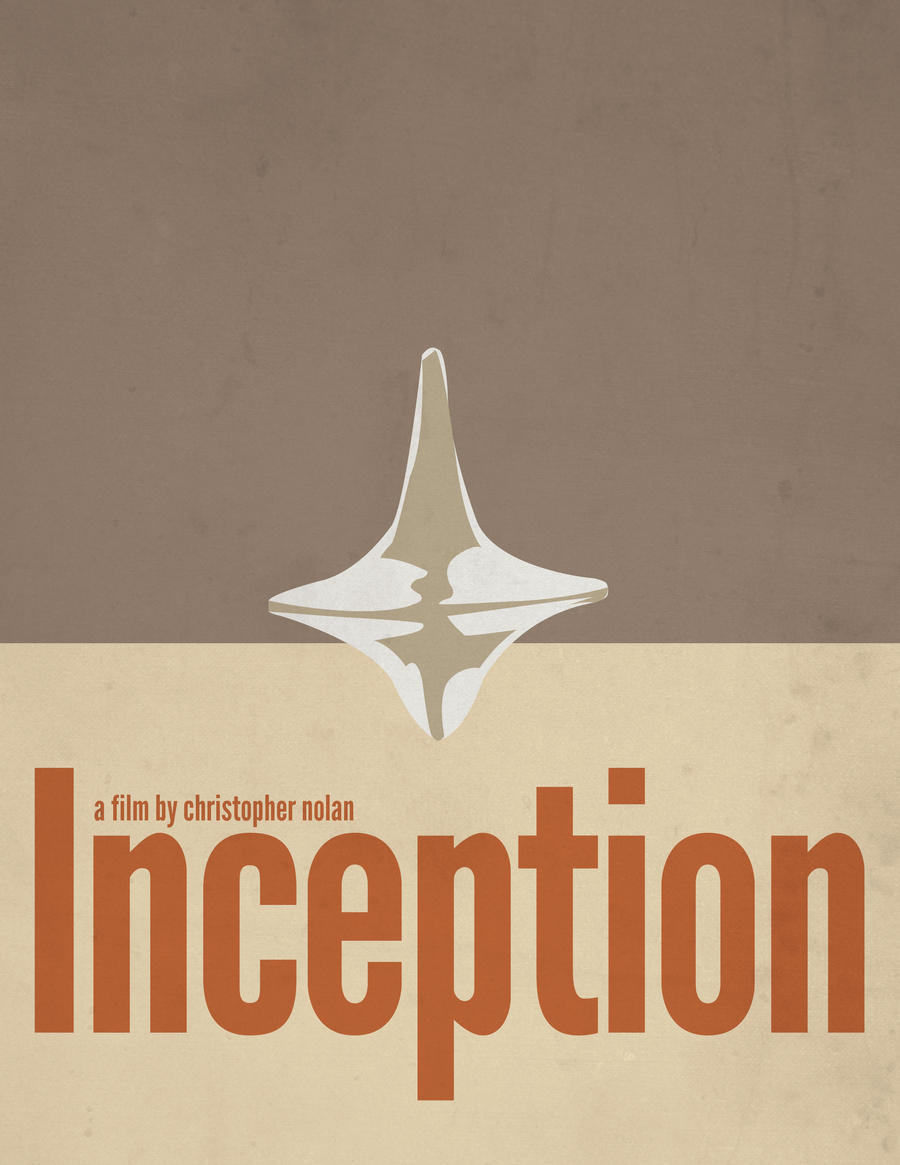

Like seriously, TMI. We don’t want any more pointless grains of information. We don’t want to be manipulated into spending our money a certain way. We don’t want to be  A new movement that seems to have been gaining footing in pop culture over the last few years is the design of minimalist posters. Movies and books and famous characters have been stripped down to iconic details and artistically portrayed in the simplest forms. Superheroes may be reduced to the shape of their mask. Great scientists may be trimmed down to a few crossed lines. Epic films may only contain a single object. This form of stripping down is art in its purest form. Like the naked body, untouched by makeup or product, not hidden behind a layer of cloth, shows the true beauty. It is fruit, freshly plucked from the tree. Unadorned, it is the most delectable.

A new movement that seems to have been gaining footing in pop culture over the last few years is the design of minimalist posters. Movies and books and famous characters have been stripped down to iconic details and artistically portrayed in the simplest forms. Superheroes may be reduced to the shape of their mask. Great scientists may be trimmed down to a few crossed lines. Epic films may only contain a single object. This form of stripping down is art in its purest form. Like the naked body, untouched by makeup or product, not hidden behind a layer of cloth, shows the true beauty. It is fruit, freshly plucked from the tree. Unadorned, it is the most delectable. Plus, these posters embody something that advertisements never can. A wholesomeness. A genuine appreciation for what the topic stands for. They are not trying to sway viewers into buying some product or conforming to some new trend, but simply provide something we can appreciate. It is simplifying an artifact of pop culture that would otherwise be overly bedazzled in manipulative tricks. The art of making the complicated simple is the threshold of beauty. Our attraction is sparked in the simplest of ways. We don’t like clutter, so show us the fruit.

Plus, these posters embody something that advertisements never can. A wholesomeness. A genuine appreciation for what the topic stands for. They are not trying to sway viewers into buying some product or conforming to some new trend, but simply provide something we can appreciate. It is simplifying an artifact of pop culture that would otherwise be overly bedazzled in manipulative tricks. The art of making the complicated simple is the threshold of beauty. Our attraction is sparked in the simplest of ways. We don’t like clutter, so show us the fruit.