Okay, here is my take on Black & White photography: it’s very difficult, it can be very beautiful, and 85% of the time it doesn’t work.

Many beginner photographers resort to B&W filters for the “artistic” look they give, but it would be a lie to state that professionals refrain from it – it might be a controversial opinion, but every time I see B&W photo entries among the winners in competitions like the World Press Photo, I just can’t help but think that some of them probably just didn’t look too interesting in color and were never meant for a B&W edit. They are supposed to create an illusion of dramatism or darkness, but if other aspects of the photo don’t speak for themselves this will just not work. I believe that what makes a remarkable B&W photo is that it was meant to be one from the beginning.

Maybe my aversion to B&W photography comes from the fact that many times people use B&W filters to cover up white balance and color mistakes, which I am definitely guilty of as well. I certainly hope you never find my early photography anywhere online, but if you do, you’ll understand why I usually avoid the B&W editing altogether.

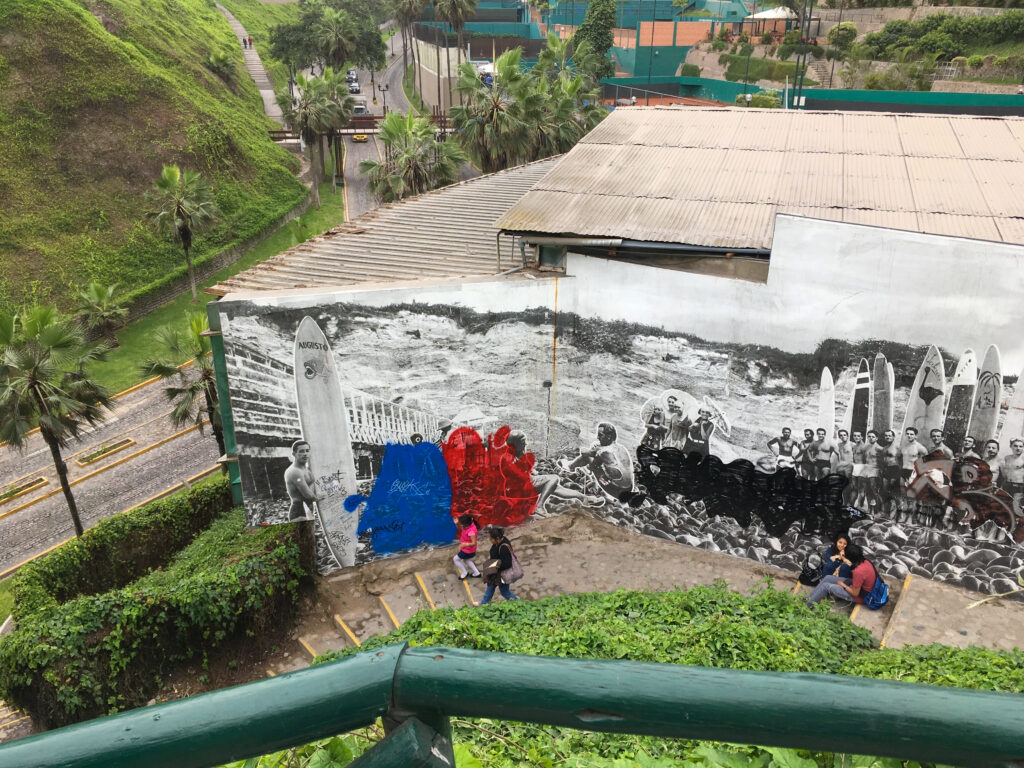

To give you an idea, here are some good examples of when I tried to ‘cover up’ bad photography with B&W editing.

The first photo you might have seen already when I posted it for Women’s Day. It is a shameless cover-up, it’s not as bad as some other ones, but you can see where it came from: I had an unfortunate white balance issue that messed up my colors (they are very greenish and I still think this one was actually slightly edited which means the original was worse), and since my old Sigma didn’t do so well in the dark, it was almost impossible to fix it in Lightroom due to so much noise*. It is still a somehow intriguing photo, not because it’s B&W but rather due to the subject. The photo on the right is some kind of an attempt at “artsy” photography from a few years ago, and as you can see it would match an Instagram story better than a photographic portfolio. B&W didn’t fix the composition or lighting issue, nor did it make it artsy.

That’s why I genuinely think that the best B&W photos are the ones that are planned as such from the start. It’s a play between light and shadows, it’s knowledge about what colors give what shade on the greyscale. B&W photos can be truly captivating and are a form of art that is very difficult and very subtle, but because B&W filters became a rescue for our photographic failures, we are bored and unamused when we see a good B&W photo “in the wild.” Don’t get me wrong, you can absolutely discover that your photo can look good in B&W after taking it too – just don’t treat the edit as a plan B in an attempt to save what is simply not that great of a photograph.

I am definitely yet to train myself in B&W photography, but for now, I am mostly a shameless judge. However, I do have some attempts I consider rather successful (at least compared to my previous ones, attached above). While the composition still requires some work, I like these (pro tip: architecture is a good subject for your early B&W photography). Moreover, these were taken by an Olympus OM-1, an analog camera, which gives them a special feel.

This is it for now, but I will continue the topic next week when I get into editing and how to turn your colored photos into B&W ones while avoiding some cliches and common mistakes. Maybe I will try to find some external sources of B&W photography I really like so you can see the true art behind it. It is definitely not easy, but it’s easy to mess up – but more on that next week.

-Tola

*when you can see “grain”, especially in the dark parts of your photograph