You only ever see your own life fully. We are ignorant of any moment, large or small, that occurs beyond our limited eyesight. It is a breadth of ignorance too enormous to ever be acknowledged. There are billions of human lives, living and dying, and we can only feel one. Yet, inevitably, those other lives will push and pull on our own. Collisions between lives, then, are unexpected. You will never know who is significant until your self-centered perspective, so carefully cultivated, is in shambles all around you. In the film Parasite, the Kim family hope to use that same egocentric, obliviousness to trick the rich Park family and climb up the economic ladder. But they are, after all, subject to that same blindness. The collision between the two families, then, is a fascinating one, even more so because of the director and writer of the film, Bong Joon-Ho (Snowpiercer). Parasite is currently showing at the State Theatre. Tickets can be bought online or at the box office ($8.50 with a student ID).

Category: Film

REVIEW: The Lighthouse

A24’s newest film follows two lighthouse keepers in 1890s New England. Director Robert Eggers chose to shoot with vintage cameras and a constricted aspect ratio, all in black and white. To further enhance the setting, Eggers took great care to ensure all of the dialogue was period-accurate. As a result, the audience truly feels like they are on the island with the two characters. The Lighthouse is unique in the sense that it is more about the viewing experience rather than its technical elements.

That being said, while the film successfully brought the audience into the story, it was almost too successful. As the film progresses, the characters spiral more and more into madness, and it is easy to feel lost and overwhelmed. The film feels stagnant while Robert Pattinson and Willem Dafoe spout pure lunacy at each other and envision inexplicable and disturbing images. It is clear that the characters are developing more and more towards insanity, but it feels like the story is not progressing at all.

The issue with the pacing and plot development largely arises from the fact that the film is very predictable. Dafoe’s character often speaks in cryptic superstitions and warnings that are actually not at all cryptic, instead laying out what will happen in the film. The viewer knows exactly in what direction the story will progress, but it takes the film a while to build up to the climax. The viewer is left feeling restless and impatient, and the just-under-two-hour runtime feels much, much longer.

Simply put, watching The Lighthouse is exhausting. I personally would rather be exhausted by a film because I was emotionally invested in it rather than because I was also being driven towards hysteria. Still, it is very impressive that Robert Eggers was able to craft such an engaging and enthralling experience. Both Dafoe and Pattinson give masterful performances as well, as Dafoe expertly weaves comedy with authority and intensity. He starts at 100%, and ends at 100%. On the other hand, Pattinson starts with a more subtle performance, one that hints at an edge to his character. It is how he is able to underplay what is deep inside his character that makes the moment when his character snaps so enrapturing.

Ultimately, The Lighthouse is not for everyone, but I would still recommend seeing it. It is a very unique kind of experience, and it would be a shame to miss out on it.

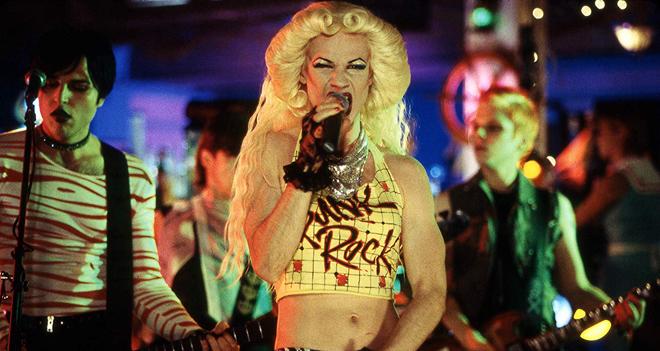

PREVIEW: Hedwig and the Angry Inch

Hedwig and the Angry Inch is a movie first released in 2001 about the life of a German emigrant living in a trailer in Kansas. She is the victim of a botched sex-change operation, and the movie follows her, as an “internationally ignored” rock singer, as she searches for stardom, and maybe even love.

The movie originated as a Broadway musical, and was eventually translated into film. John Cameron Mitchell starred in and wrote the musical, and he also stars in and directed the movie as well. I have always had this musical on my bucket list, especially after Darren Criss became the star. And if I can’t see the musical, the movie is the next best option!

Hedwig and the Angry Inch is playing at the State Theater on Friday (Nov. 8) and Saturday (Nov. 9) at 10 pm.

Trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4p9mPhGo1j0

Friday tickets: https://secure.michtheater.org/websales/pages/TicketSearchCriteria.aspx?evtinfo=647021~c76be4f4-22b5-4bed-a89c-7def863b8c53&

Saturday Tickets: https://secure.michtheater.org/websales/pages/TicketSearchCriteria.aspx?evtinfo=647022~c76be4f4-22b5-4bed-a89c-7def863b8c53&

Just a side note: This movie is rated R for sexual content and language.

REVIEW: International Studies Horror Film Fest

Another year of the annual International Studies Horror Film Fest has come and gone, and with it went my hope that they would show actual horror movies.

Don’t get me wrong; the selections were wonderfully artistic and variable in tone and theme and texture. All three featured original plots and unsettling undertones. They each force a bit of creepiness into one’s idea of the world, while remaining quite beautiful. However, I would have appreciated at least one fully, overtly gruesome movie in the program. The gore was almost nonexistent in all of the films, limited to a few scenes of graphicness apiece. I found myself groaning over the romantic subplots and long periods of calm while trying to focus on the main stories and character dynamics. On Halloween, I need fear to rule. This can be done in complex, story-rich, writerly ways; the artistry of a film need not be sacrificed. Thus, even if the fest’s planners intended to get together a group of intellectually stimulating movies, they could have done so while giving the audience a little more of a scare.

Face was basically CSI or Criminal Minds in all it accomplished horror-wise. The whole movie seems cast in shadows, plagued by an uninspired soundtrack and TV-drama style acting. But the pace of the film was perfect, a slow reveal of a shocking truth whose slime does something venomous to the psyche of the audience.

The Lure was an entire musical, and certainly the only movie of its kind, however impossible to define that may be. The heavy glamour of the strip club pairs so well with the mythology surrounding mermaids, and the girls’ dead stares were a perfect balance for all the life in their musical numbers. The unwholesomeness of the young girls participating in this business combines with the sexual power of mermaids in lore to create an uneasy feeling for the audience, similar to the trickery sailors face in all the stories. But even with the violence and the complex uneasiness, this movie is far closer to a comedy than a horror film.

Dogtooth seemed like something I should have enjoyed, given that its creator is the same man behind The Lobster (a movie which, after watching, made me feel so unmoored that I literally held onto street signs as I walked to the bus stop, certain I’d blow away with the wind). It bears obvious similarities in how the cast is directed to act (basically emotionless, flat) and the minimalism of the indoor environments. But it falls short of creating the same level of effect for me that Lanthimos had in his later film. I think he realizes later in his career that there is a limit to the lack of expression he can write into his actors and the barrenness of the landscape before it becomes too offputting for the audience to focus on the story. In short, I got bored, and the beauty of the expertly done lighting and the carefully constructed garden space did little to change that. Some emotional music would have gone a long way.

Truly, these movies have tons of artistic value to consider and appreciate. In another sort of film festival, they would be great additions (and indeed, they have been inputs of such festivals as Cannes and Sundance), but I still hold that they are unwise selections for a true horror fest. I hope that next year, they have more time in the gallery to show an extra movie that a Halloween lover would appreciate.

REVIEW: Monos

Monos begins high above the rest of the world. So high, that one can watch the fluffy tops of clouds as they meander across the sky. So high, that trouble seems a distant, unthinkable thing. But trouble finds its way everywhere eventually. It will hunt you down with relentless feet and unbounded strength. For the eight teenaged soldiers stationed atop a Columbian mountain, trouble comes in the form of a dairy cow. Or maybe that is an oversimplification. Maybe trouble was always there, awaiting an opportunity to rear its bloody head. Because these are isolated teenagers, orphans really, conscripted into a war they don’t fully understand. The tragedy is that for this group, peace was never truly an option.

Choice is always lacking in Monos. There is no escape from this beautiful, isolated place. They are trapped together and so, together they form a makeshift family with makeshift names. Throughout the film, the teenagers only use pseudonyms. Their false names are like flimsy costumes, war-like personas that they assume as they pretend to be soldiers. Still, for all their bravado, they are young. There is so much potential in their youth and so much danger. Youth is corruptible and all that potential can quickly turn sour. The question becomes if any of that budding hope can survive in such an unforgiving environment. The adults, those who should be caretakers to the children, hand them guns instead. And so, when there is no one to turn to and nowhere to go, what can they do except obey orders and shoot to kill? In the rampage of war, they are the most helpless pawns of all. In their attempts to gain a semblance of power for themselves, the teenagers can only imitate the system that they know, one of violence and oppression. Even imagining a world without endless conflict seems impossible.

The film, though, is not devoid of hope or beauty. There is no lack of beautiful landscapes, even when they become marred by blood. The stony majesty of the mountain is framed in beautiful wide shots by cinematographer, Jasper Wolf. The camera soars above all, to the heavens, rendering every person small and insignificant. Against the vast expanses of sky, the teenagers are only black shadows. They are rendered indistinct, without detail as they stare into a universe that seems infinite. The tragedy, though, is in the limitations. During their brutal training sessions, the frame becomes claustrophobically tight on their faces. We see all the strain, all the terror of failing or showing any weakness. For, no weakness will be tolerated. They are trapped again. The way Monos alternates between different kinds of shots is unsettling. It throws audiences into an uncomfortable situation where nothing is quite safe. Even during the moments of exhilaration, when there exists the possibility of a haven within the confines of war, there always looms a sense of dread. This is reinforced by an intermittent score that kicks in without warning and ends in a searing screech. Otherwise, the film is almost entirely silent, broken only by snatches of dialogue.

That dialogue is delivered with equal amounts of veracity and vulnerability by the young actors. Especially prominent is Sofia Buenaventura as Rambo. Rambo is the gentlest of the group and therefore, tasked with the most inner conflict. She has still not quite given up the idea of a different life, one that she can see with eyes that express every feeling. But even the harshest of the teenagers do not begin as stony killers. They are capable of happiness, capable of openness. Gradually, though, as they close their hearts, as they embrace violence, the actors become harsher too. Their expressions sharpen and bodies move more wildly, desperation in every tendon. But no matter how hard they strive, they can’t escape. Their actions are meaningless in a grander scheme.

Monos is an unrelenting ride. It alternates between loud and quiet, between small and large. However, for all its varying extremes, there is one overwhelming direction. Down. The film plummets from the beautiful mountaintop into the depths of the jungle. We fall with it, knowing that there is nothing to waiting to catch us at the bottom.

REVIEW: Jojo Rabbit

This weekend marks the opening of Jojo Rabbit, a movie about a young German boy named Jojo, who learns that Jews are not as bad as he has been taught, through a blend of irreverent humor and surprising seriousness. However, I think that despite the advertising, I did not feel this movie was as focused on being an “anti hate satire” as it so claimed. Instead, I saw it more as a commentary on the opinions people may have about others who are unlike them, and how easily stereotypes can be broken. Young Jojo completely assumes the Jewish girl he finds hiding in his attic is the epitome of the devil, however he learns that when you get to know someone, they are not always the people that others claim them to be. While there were definitely an abundance of comedic moments, I was surprised by how many times I felt emotionally moved, either to sadness or contemplation. In between the humor, there were scenes that were very real and addressed the intensity of the time period, reminding viewers they they were, in fact, watching a movie about the mass genocide of human beings.

As a Jew, I found some of the scenes containing actual events to be a little underwhelming, in terms of how serious or intense they should be. While I do understand that it was a comedy, these events are not to be skimmed over. The beginning of the movie really threw me off in this respect, as it showed people enjoying heiling and having a good time at political rallies. The teenage girl who lived in the attic did not seem nearly as unhappy as you’d believe someone living in a small space for probably over a year might be, and some of the aspects of the war scene were not as traumatic as you’d imagine they would be for a young boy.

The character of Hitler, played by Taika Waititi, the director, was an integral part of both the comedy and profundity of the movie. He brought an interesting twist to the idea of an imaginary friend as he was at times scarily realistic, but at others, seemed just like a 10 year old boy. Waititi played such an interesting role, as both a dictator and a kid’s imaginary friend. At first, he was just funny commentary on Jojo’s life, but continued to lose his influence over Jojo and got more and more terrifying as Jojo began to befriend the girl in the attic. I really enjoyed Jojo as a character as well, and the arc that he experienced was very uplifting as he learned that Jews are not mind-controllers with horns. It made me hopeful for our future, that if we can get to know each other, maybe those who are different than us will not seem so scary after all. As a female, and a Jew, I related very strongly to the girl who was being hidden in Jojo’s house. She represented the reality of the situation and the fear of having such a dangerous and uncertain future very well. Her stories of her previous life being ripped away were intensely tragic.

Overall, I do not think the movie was as good as the critics are raving, but it was definitely an experience I enjoyed. Its perceptivity of how different people can learn to understand each other as well as its humor made it a movie worth going to see.