Like a telescope, the camera takes a lens to both distance and bring closer the image on the other side: something captured which previously went unexplored, an instant in time that is taken and set into memory. In both instruments, what we see is something we’ve created with the help of the setting of the time, the cultural moment, the positions of various actors across a space. Just as a telescope offers a look into the positions of an infinite number of celestial bodies in relation to one other, a camera creates a record of social climate, inequities and labor for justice.

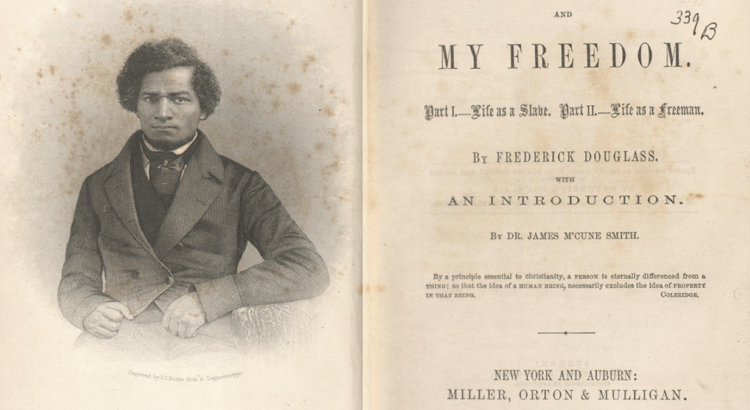

But that’s enough for botched and rambling similes. The Clements Bookworm discussion was a great addition to simply viewing the online exhibit alone.  Samantha Hill was invigorated as she spoke on the pieces in the collection, highlighting many Michigan photographers and communities. There wasn’t time to go through each picture in the detail it seemed she wanted to, but her summaries did a great job to show overarching themes and the changing trends of the representation of Black individuals and communities over nearly two centuries. The reversal of negative stereotypes/caricatures in portrayals of Black people is an ongoing, complicated process which the artistic greats of history, like Frederick Douglass, expanded into new media.

Samantha Hill was invigorated as she spoke on the pieces in the collection, highlighting many Michigan photographers and communities. There wasn’t time to go through each picture in the detail it seemed she wanted to, but her summaries did a great job to show overarching themes and the changing trends of the representation of Black individuals and communities over nearly two centuries. The reversal of negative stereotypes/caricatures in portrayals of Black people is an ongoing, complicated process which the artistic greats of history, like Frederick Douglass, expanded into new media.

As photography became omnipresent, saturating first the print news and eventually dominating the Internet, it grew in accessibility, challenging everyone to really consider their identity, how they’d like to be perceived, where they fit into the rest of society. From the first powerful, dignified portraits of Douglass to today’s glamorous Fenty photoshoots, self-expression and framing of POC has evolved and strengthened with race discourse and culture, continuously inspiring new questions and conversations, driving our society towards equity.

Hill discussed The Colored American Magazine, one of the first periodical publications to celebrate Black art and achievements. I wish she ha d talked a little longer on this, given the great influence of media representation, especially after the Internet became ubiquitous. She brought it into the present a while later, with examples of former President Obama in magazines.

d talked a little longer on this, given the great influence of media representation, especially after the Internet became ubiquitous. She brought it into the present a while later, with examples of former President Obama in magazines.

For me, the media brings up an interesting thought: how does putting one’s representation back into the hands of another change the resulting image? Whitewashing in magazines and Instagram ads is an obvious example, but what about posture, facial expression, two important factors in Douglass’ revolution? The style of dress, the position of the subject in what kind of background? We’ve seen a regression of some kind, or rather a continuation of what had already existed. What would Douglass say to us if he saw how his vision and goals have evolved?

For more online events from the staff at the Clements Library (which I’d definitely recommend attending!), check out their Facebook page, William L. Clements Library. Discussions occur fairly frequently, covering a range of art and history topics. If you’d like to watch the recorded webinar from this exhibit, you can find it here.