The final frontier. Glittering, sharp edged galaxies and exploding supernovas. Voids without end swallowing light and time. Majesty beyond measure, splendor beyond comprehension. Ad Astra imagines a time in the not too distant future, when the extraordinary becomes ordinary, when all the glimmering space becomes just another excuse for mankind to ignore its problems. It is a slightly gloomy proposition; yet, it is also one that seems, in all probability, the most realistic outcome. For as easy as it is to imagine the limitless possibilities of the cosmos, it is even easier to imagine humankind finding a way to corrupt the untouched unknowns. For, even as we travel further into the galaxies beyond, we cannot travel beyond ourselves.

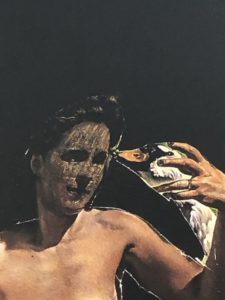

Roy McBride (Brad Pitt) is a man who knows his limitations more than most. We hear his voice first. Calm and measured, he completes the mandatory psychological test, authorizing him as fit to perform a spacewalk. Composed and deliberate, he walks through a corridor, filled with cheerful colleagues. They greet him with enthusiastic smiles and a respectful, “Major”. He nods in return. Every word so considered, every action so purposeful. And perhaps, Roy is right to do so. As an astronaut, life is a delicate thing, easily destroyed by the slightest step outside of regulation. Surviving in space means dedicating every possible scrap of mental and physical energy to enduring. It is a harsh life, one that has helped alienate Roy from any semblance of a personal life. We are granted only glimpses of a previous relationship with Eve (Liv Tyler) before Roy compartmentalizes, shutting out pain. Acknowledging pain is a distraction after all, and Roy is far too practiced at drifting from his emotions instead. And so he does, until Roy is called on upon to find the man who caused him to fence off the world in the first place: his father.

Like its main character, Ad Astra is lonely. Much of its run time is devoted to contemplation of beauty, of emptiness. It is the beauty and the emptiness, after all, that define mankind’s expansion into the solar system. As Roy notes in one of his many (only sometimes tedious) asides, the development of viable space travel has not substantially changed human nature. Even the rocket trip to the moon is dispiritingly familiar. The same cramped seating with limited leg room. The same wrinkled in-flight magazine. The human race may have figured out a path to the stars, but it still can’t outgrow its ceaseless need to demand payment for flight upgrades. The contrast between the extraordinary and the mundane is what differentiates the film from its more wide-eyed counterparts. Despite its lunar landscapes and its Martian set pieces, what is most stunning about the film is how it makes this fantastical future seem all too possible. This probable tomorrow must have seemed all too tempting to Roy’s father, H. Clifford McBride (Tommy Lee Jones). A vision that must have been even more tantalizing than staying home to take care of his young son. It is that tender pain consistently jabbing into Roy’s heart and wounding Brad Pitt’s composure throughout the movie. A pain that tells him that he wasn’t worth enough to his father. It is that pain is what carries the film most realistically through its travails through space. Like all space films, Ad Astra risks drifting beyond its Earthly ties and disengaging from audience interest. But it remains committed to the story of Roy above all, never losing focus among the stars.

Ad Astra is a film as interested in the vastness of one man’s psyche as it is in the immensity of outer space. And perhaps, this limits the scope of the film as it tunnels deeper and deeper into Roy’s mind. But perhaps, the limits are precisely the point. We are not unrestrained beings. We are held back by all our human humdrum, all our pleasantries used to cover up unpleasant realities. We get lost because we want to lose ourselves, for a little while anyway. There is no more beautiful place to get lost than outer space.