This event was a talk. Any music played was to support a point he was making in the talk. Still the whole reason I attended this talk was to hear Yo-Yo Ma play the cello. Attending a 90-minute talk to hear 3 minutes of cello playing may not be the most logical reason, but I’m pretty sure half the audience was on the same boat as me.

Yo-Yo Ma’s first words on the stage were music to my ears (pun intended). He said ” Let’s start off with some music”. My joy turned into curiosity and confusion when instead of picking up the cello he walked over to the piano. He played some of Bach’s Goldberg Variations. I was disappointed because I found his piano playing mediocre. It was a slow song, yet he was hunched over the piano looking intently into the sheet music like an unfamiliar student learning a new piece. It didn’t feel graceful, his hands were bouncing around with emotion, and I even thought I heard some mistakes. If this was just a regular piano player, playing this song, the size of this audience would decrease a hundred-fold. To his credit, he played the exact same piano piece to end the show. Although not great, I thought it sounded better the second time.

All of this piano playing was to make the point that music is based on variation and themes. In music, variation is change revolving around a theme, and in life, it is the exact same. Life is countless variations spiralling around themes. To my surprise, Yo-Yo Ma is a fantastic speaker. He is extremely cheery, full of excitement, and has a soft toned friendly voice. His talk was very interesting, and I found myself engaged the entire time, even though it was not the reason I was there. I will summarize the points I found most impactful.

The greatest music teachers don’t teach their students to be like them, they teach their students to listen to the world around them. When Yo-Yo Ma performs, to keep his repertoire fresh he plays every song like it is the last time he will ever play the piece. In college, he went through an extremely painful back surgery to fix scoliosis. He was given a lot of pain medication, but what he said got him through the pain was Brahms second symphony playing over and over in his head. I love music more than anything in the world, particularly indie rock and blues rock. I could never imagine San Cisco getting me through back surgery. Hearing him say this made me wonder how amazing and powerful it is to truly appreciate classical music. I realize how much more complex and beautiful classical music is than indie and blues rock, but I just find a hard time connecting with it. Yo-Yo Ma obviously has an understanding of classical music, from all his experience and practice, that I could never obtain, but hearing him say this made me feel as if I was missing out on something in life. This statement got me to vow to listen to more classical music. Everything humans do is to give ourselves meaning, and culture is part of this. Culture gives us meaning, and music is an abstract way of representing culture. Therefore, music gives us meaning as humans. How culture evolves will determine how we evolve as humans.

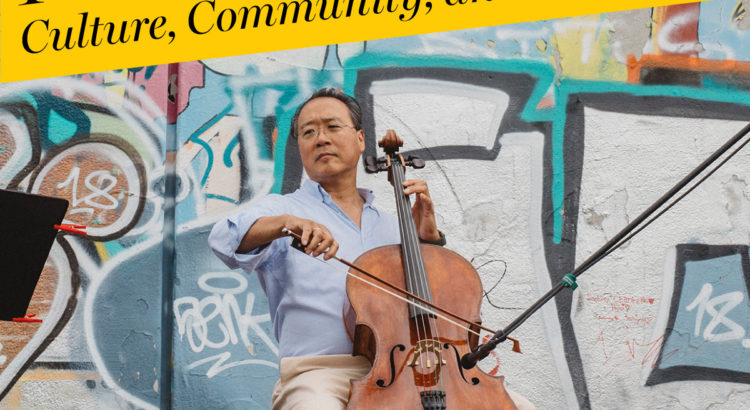

I was able to hear him play the cello twice. Once where he played a song and once where he juxtaposed scales with arpeggios. Unlike his piano playing, he is a master with the cello. Every bow movement is perfect as his fingers slide around the strings. My favorite part was when he was playing the scales and arpeggios he would occasionally play this ugly sound. It was a low grumbling note that still sounded beautiful mixed in with the rest of the notes. It was then that I understood the point he was trying to accomplish. He was showing us that the conflict between scales and arpeggios sounds beautiful together.