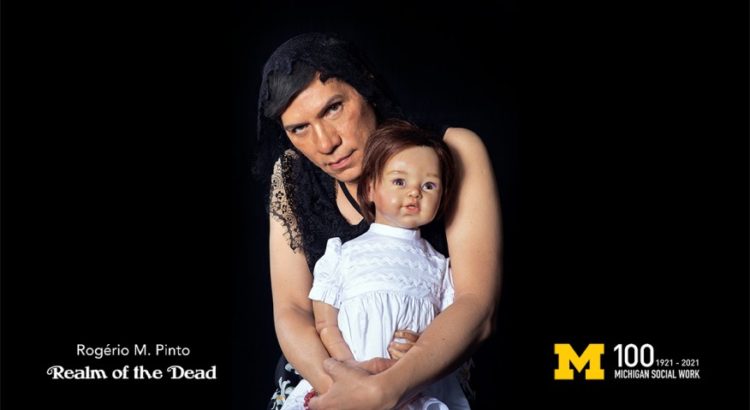

This Thursday, I attended Realm of the Dead, an installation at the School of Social Work. Comprised of more than 30 suitcases, Realm of the Dead is a reflection on tragedy, grief, and identity by Rogerio M. Pinto, a professor of Social Work at UofM.

The walk into the building was supplemented by a drumline performance, waking me up and welcoming me into a lobby where videos of the Rio Carnival played. I was handed a small, white, rectangular box with a letter and number denoting where I would be located once we moved downstairs. A suitcase full of wish ribbons lay open: curious, I peeked inside, and an usher offered to help me tie one around my wrist. The ribbons read “Realm of the Dead.”

When the performance was set to begin, the audience descended a set of stairs to the lower floor. The ritualistic feeling of moving down the stairs, down to the Realm of the Dead, accompanied by the drumline’s beat, felt sacred in a way. Hushed, the audience made their way to the suitcases, laid out in a grid. The artist, Rogerio M. Pinto, sat next to a doll in a suitcase casket, holding a rosary, murmuring inaudible words. The drumline came to a halt, the suitcases were opened to reveal insides filled with art, and Pinto began to tell his story.

“Emotional baggage—” Pinto explains. Many people in the world can fit all their belongings into one suitcase. Could you carry everything with you in one bag? How about one small box?

Pinto tells the story, in pieces, of the death of his baby sister Marilia. She was 3 when she was killed in a tragic accident. Pinto unfolds the effect of this tragedy on his family and his identities growing up. Both his words and the suitcases weave a deep exploration of grief in relation to gender, body, ethnicity, immigration, and class.

Throughout the exhibit, suitcases filled with small items asked each viewer to take the things that reminded them of someone or something they had lost. We would fill out boxes with these things, and at the end, there would be the option to keep it or to leave it in the Realm of the Dead, allowing it to become part of the exhibit. Moving through the exhibit, I felt my box grow slightly more full with the notes and items I had collected, but I also felt myself grow heavy. Listening to Pinto’s story of grief, remembering my own.

We keep the dead with us, in us. My mother passed away 2 years ago, leaving me feeling helpless and crushed. I am still grieving her. While this performance left me remembering this loss with a heavy heart, I found myself comforted by the reminder that a part of her is in me and always will be. I choose to carry her with me. I grieve. “My sweet sister, no longer here, no longer on Earth.” Pinto holds his hands to his chest. She lives on, he says, in him—”Can you see her?”

This exploration of grief through art and performance was so beautifully touching to me. I am thankful to Pinto for sharing his story, and in this way giving the audience a space to search their own losses. To honor the Realm of the Dead.

Even so, the recliner dominates the space, sending chilly tones throughout the warmly lit interior. Other striking plush components include the ‘pillow guns’, a set of three flaccid rifles mounted to the wall, and the ‘Born & Bred Beer’ beer cans casually littered on the recliner’s side-table. Chenille fabric, what the majority of the installation consists of, is immediately distinguishable through its tufted, caterpillar-like texture and iridescent appearance. These characteristics make the textile a popular choice for sofas, baby blankets, and other items that make direct contact with the skin. Needless to say, I was fascinated with the artist’s approach to materiality and her manipulation of sensory elements with chenille that served to contradict and even amplify the viewer’s psychological responses to derogatory imagery.

Even so, the recliner dominates the space, sending chilly tones throughout the warmly lit interior. Other striking plush components include the ‘pillow guns’, a set of three flaccid rifles mounted to the wall, and the ‘Born & Bred Beer’ beer cans casually littered on the recliner’s side-table. Chenille fabric, what the majority of the installation consists of, is immediately distinguishable through its tufted, caterpillar-like texture and iridescent appearance. These characteristics make the textile a popular choice for sofas, baby blankets, and other items that make direct contact with the skin. Needless to say, I was fascinated with the artist’s approach to materiality and her manipulation of sensory elements with chenille that served to contradict and even amplify the viewer’s psychological responses to derogatory imagery.