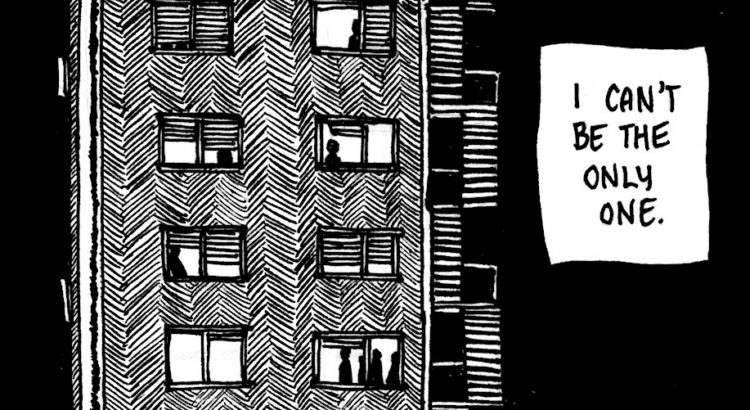

There are periods in my life where I completely fall out of love with fiction. I’m not entirely sure why it happens, but suddenly there’s a switch that goes off in my brain, and I hate even the concept of fiction and media– the falsity of it, the mere entertainment, the meaningless indulgence in the aesthetic, as we all slink closer and closer to our deaths, and the earth keeps turning, and we watch a movie or turn the pages of a magazine or forget a poem.

For example, at some point in sophomore year of high school, I read Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe by Benjamin Alire Sáenz, a coming-of-age novel about the unparalleled bond between two boys. I still remember crying on the floor of my bedroom past midnight when I was supposed to be doing homework, and just let the book completely wreck me (it’s a very good book, you should read it), and when my mom walked into the room, I had nothing for defense except “It was a good book.” I realized that I couldn’t invest my time into a book without getting so attached and emotionally invested. It controlled me. After that, I went for months without reading anything– I got too invested, it hurt me too much, it surprised me with the pliability of my own emotions. I wanted to dominate my emotions, not let fiction dominate them.

I got over that, of course– it’s silly to have such powerful connections to books and movies and take it so innocently for reality. I developed a crucial distance from literature, almost as a defense mechanism to not let to get it to me too much, not allow it to break me and tear me apart, scare me or enthrall me. I started to see it from an “intellectually” distanced standpoint, observing it from the superior perch of examining craft and theme and symbolism, stroking my monocle and saying things like, “Ah yes, the intertextuality…”, or, “The symbolism of this hat demonstrates that…” And that helped me understand art, helped me tame the wild and crazy and unexplainable forces of literature.

Coming to college, things started to feel too crystallized. I stopped connecting to the things I was reading as much, and that may have just been because even though we were reading “diverse literature” in my English classes, it was still taught by white professors to a mostly white student body, creating a strange dissonance with the work. And more than that– the Western-centric perspective of everything I read was so glaringly obvious to me, I couldn’t connect to it at a personal level. The emotional connection I’d once had to art– the kind of cosmic, universe-warping feelings that had made me cry in my childhood bedroom– had all gone. They were replaced with terms and definitions and critical theory. Wasn’t it supposed to move me?

I can’t say I’ve found conclusions to my constantly fluctuating relationship with literature. But I have found a little reminder of why I love what I love. Columbus is a movie about the unexpected friendship between a homebody architect-enthusiast and the son of a renowned architect set in the town of Columbus, Indiana, known for its modernist buildings. In one of the lines in which the main character is trying to explain to Jin why she likes a building, he stops her and asks if she likes the building intellectually.

“I’m also moved by it,” she admits.

“Yes!” He says. “Yes, tell me about that: What moves you?”

“I thought you hated architecture.”

“I do. But I’m interested in what moves you.”

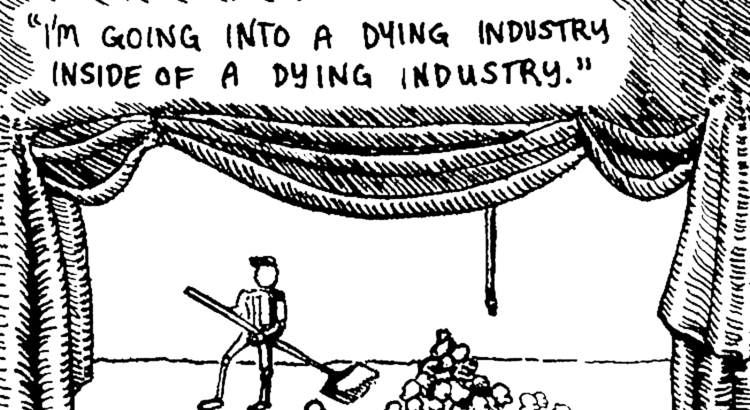

As I most likely move towards a career that intellectualizes art, I must ground myself to my own heart, and remind myself to stay true to the contents of my mind. I want to be committed to that which moves me.