I’ve been a part-time student of minimalism for about a year now. My living space has been stripped to the essentials, my number of possessions has decreased, and I’ve employed pretentiously simple fonts on my website. So yeah, I’ve become that guy.

at least i dont boycott uppercase letters and punctuation right?

Anyway, despite my obsession with minimalism, I’m also a pragmatist. In my studies (scouring r/minimalism), I’ve  stumbled across some problems regarding logistics. Houses, and living spaces in general, seem to be one of the major obstacles to overcome in regards to minimalism. As modern-day humans in America, we take up a great deal of space–more so than we need to survive. For the aspiring minimalist, a feeling of hypocrisy may settle as she realizes the obscene amount of space she consumes in her residence. But most of this is outside of her control; apartments only offer a such small rooms and lots in neighborhoods often have expansive lawns and wide garages. It’s frustrating, as a minimalist, to live in such spacious areas. It would be wonderful to live on the edge of paper–in the peripheral spaces unused by the general public. While only a dream in America, this is a Japanese reality.

Many of these tiny houses have popped up in recent years. They’re called kyoushou juutaku in Japan and are designed to make use of liminal spaces, such as odd gaps between larger buildings or narrow strips of land beside roads. This phenomenon, while quite un-American in their small size, are actually inspired by the Western ideals of independence and home-ownership. Globalization has exposed the Japanese to the “glory” of an American lifestyle, and they have appropriated an aspect of that culture into their own. While the complications of this influence are obviously too numerous for the sake of this blog post, there’re some cool things to learn from this.

The first is a matter of zoning. Considering most cities have restrictions on the lot-size one can sell or lease, opportunities for these tiny houses are limited to certain regions. Be under city or county jurisdiction or at the discretion of the civil engineers who define the infrastructure of a city, tiny houses can only appear if they are permitted. Once something exists somewhere, however, the opportunity for it to spread exists as well. If tiny houses grow become popular in Japan, minimalists around the world may one-day mimic their beauty.

The second pertains to economy and environmentalism. When cities enable their land to be used in the most efficient manner, the population of cities can increase, which correlates to a more active economy and less urban sprawl. With more people concentrated in a city, less space will be needed for suburbs and the carbon cost of commuting. Tax rates rise and more money is spent and circulated within city limits. These micro-homes can be loved by capitalists and environmentalists alike.

The third is art. While creativity is often seen as thinking outside of the box, these minimalist houses suggests that a greater creativity lies in thinking within the box. Building livable homes under tight constraints calls for a greater ingenuity and imagination than those creating on a blank canvas. Working with microscopic lot sizes, designers of mini houses generate unique and elegant solutions to transform vacant and unused spaces into welcoming homes. This movement challenges us to think not in terms of grandiosity, but in terms of class. More elegance is required to build a small house or write a short letter. The rise of kyoushou juutaku will push the limits of architecture and inspire a wave of minimalist ingenuity. Residents of tiny houses do not only live on the edge of paper, but in art itself.

Advertising creates clutter. Sides of highways are clustered with billboards waving at the thousands of drivers passing by each day. They are obstructive, bulky signs that stretch their wingspan over the surrounding trees to vie for attention. Advertisements coat the sides of websites, luring our eyes with distracting graphics and colors and mystery-inducing lines like “Language professors HATE him†and “1000th visitor! Click here to claim your free iPad†and “Meet sexy singles (like Ms. I-Swear-These-Aren’t-Implants-And-Every-User-Of-This-App-Looks-As-Sexy-As-I-Do).†They coat our cereal boxes, newspapers (for those old-timers out there), Facebook pages, daily commutes, etc. Each of these advertisements is in competition with each other, constantly swallowing massive amounts of revenue to become slightly better than their competitors. They pile up like layers of paint over a color-slut’s rented apartment. It is a desperate and futile, Sisyphean battle for our attention. As time moves on and we drown in their commercial rank, we become less willing to provide that attention.

Advertising creates clutter. Sides of highways are clustered with billboards waving at the thousands of drivers passing by each day. They are obstructive, bulky signs that stretch their wingspan over the surrounding trees to vie for attention. Advertisements coat the sides of websites, luring our eyes with distracting graphics and colors and mystery-inducing lines like “Language professors HATE him†and “1000th visitor! Click here to claim your free iPad†and “Meet sexy singles (like Ms. I-Swear-These-Aren’t-Implants-And-Every-User-Of-This-App-Looks-As-Sexy-As-I-Do).†They coat our cereal boxes, newspapers (for those old-timers out there), Facebook pages, daily commutes, etc. Each of these advertisements is in competition with each other, constantly swallowing massive amounts of revenue to become slightly better than their competitors. They pile up like layers of paint over a color-slut’s rented apartment. It is a desperate and futile, Sisyphean battle for our attention. As time moves on and we drown in their commercial rank, we become less willing to provide that attention. Like seriously, TMI. We don’t want any more pointless grains of information. We don’t want to be manipulated into spending our money a certain way. We don’t want to be

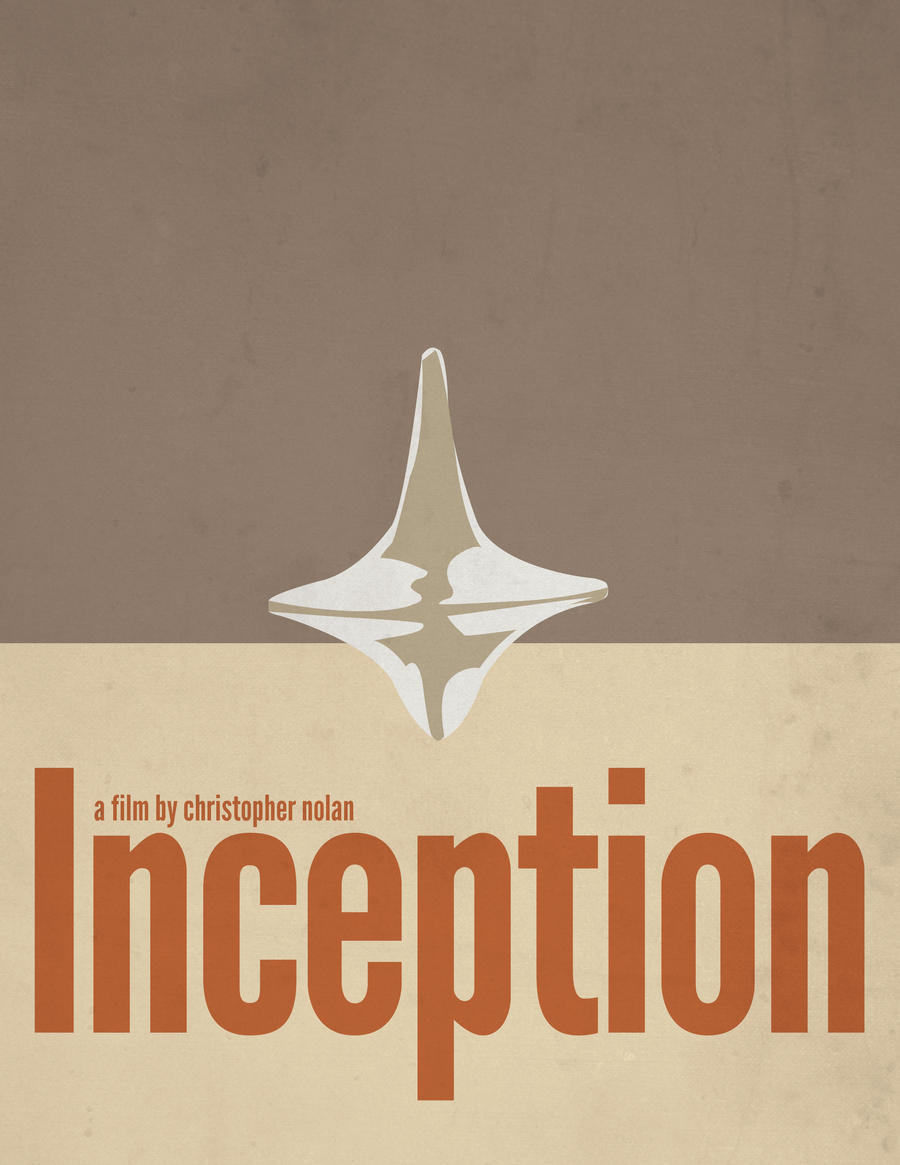

Like seriously, TMI. We don’t want any more pointless grains of information. We don’t want to be manipulated into spending our money a certain way. We don’t want to be  A new movement that seems to have been gaining footing in pop culture over the last few years is the design of minimalist posters. Movies and books and famous characters have been stripped down to iconic details and artistically portrayed in the simplest forms. Superheroes may be reduced to the shape of their mask. Great scientists may be trimmed down to a few crossed lines. Epic films may only contain a single object. This form of stripping down is art in its purest form. Like the naked body, untouched by makeup or product, not hidden behind a layer of cloth, shows the true beauty. It is fruit, freshly plucked from the tree. Unadorned, it is the most delectable.

A new movement that seems to have been gaining footing in pop culture over the last few years is the design of minimalist posters. Movies and books and famous characters have been stripped down to iconic details and artistically portrayed in the simplest forms. Superheroes may be reduced to the shape of their mask. Great scientists may be trimmed down to a few crossed lines. Epic films may only contain a single object. This form of stripping down is art in its purest form. Like the naked body, untouched by makeup or product, not hidden behind a layer of cloth, shows the true beauty. It is fruit, freshly plucked from the tree. Unadorned, it is the most delectable. Plus, these posters embody something that advertisements never can. A wholesomeness. A genuine appreciation for what the topic stands for. They are not trying to sway viewers into buying some product or conforming to some new trend, but simply provide something we can appreciate. It is simplifying an artifact of pop culture that would otherwise be overly bedazzled in manipulative tricks. The art of making the complicated simple is the threshold of beauty. Our attraction is sparked in the simplest of ways. We don’t like clutter, so show us the fruit.

Plus, these posters embody something that advertisements never can. A wholesomeness. A genuine appreciation for what the topic stands for. They are not trying to sway viewers into buying some product or conforming to some new trend, but simply provide something we can appreciate. It is simplifying an artifact of pop culture that would otherwise be overly bedazzled in manipulative tricks. The art of making the complicated simple is the threshold of beauty. Our attraction is sparked in the simplest of ways. We don’t like clutter, so show us the fruit.