Few fashion trends during the French Revolutionary period were able to create the same reaction as la coiffure à la Titus, a haircut that evoked both amusement and outrage.  Its extreme shortness was purposefully masculine, having been appropriated from an earlier male fashion trend meant to imitate ancient Roman busts.   It was also a style that was considered incredibly natural, standing in contrast to the highly powdered and structured wigs of the ancien regime. Women who cropped their hair in such a way were aggressively targeted in pamphlets, cultural journals, fashion prints, caricatures, books, and at least one play. This condemnation was, as one might expect, an overwhelmingly male exercise, with one contemporary critic going as far as to say that the women who wore the Titus were “disfigured.â€Â Regardless of the deprecation, many prominent women wore the blatantly masculine hairstyle well into the first decade of the 19th Century, continually amending it to fit changing definitions of femininity.

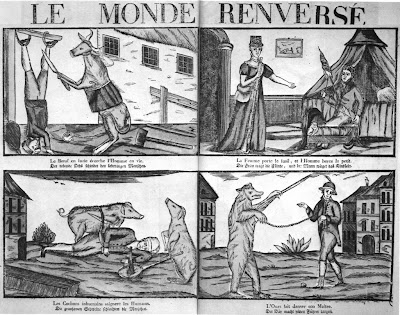

In 1804 the author of the Toilette des dames ou Encyclopédie de la beauté railed against the Coiffure à la Titus, questioning why women would forsake what was universally regarded as their most beautiful feature and opt instead for bare heads. This was something typically associated with punishment or shame. Women’s decision to sacrifice an accepted sign of femininity begged an association with cross-dressing. According to critic Rothe de Nugent in his 1809 Anti-Titus pamphlet, one of the principle aspects of revulsion found in the female Titus was the conflation between male hair and female dress, as though a Roman emperor’s head were on the body of a female. Worries over cross-dressing, long standing in Western culture, signaled that male authority could be overtaken simply by a woman’s supposition that she was not confined to gendered clothing. This criticism followed in the tradition as le monde renversé. Le monde renversé was a common theme created in 16th century children’s books meant to illustrate basic societal norms and morals through a carnivalesque inversion of hierarchies. One such image shows a woman about to go on a hunt while the husband stays at home with the children. These publications did not generally show cross-dressing, instead the emphasis was on the

reversal of one’s purpose in society, which was made entirely readable through appearance and costume by the time of the French Revolution. This print of the king combing out the queen’s hair bears clear thematic influence from le monde renversé. It not only makes Louis XVI a servant to Marie-Antoinette and a pawn in her own political desires but that her hair had become equal to and interchangeable with the crown, as indicated by the caption “Coeffure pour Couronneâ€. Regarding the verdict for Marie Antoinette’s guilt, historian Lynn Hunt wrote “the revelation of the Queen’s true motives and feelings came [above all] from the ability of the people to ‘read’ her body.â€Â Or, at least, the belief that her body could be read.

The implication of Le Monde Renversé, and bear it in mind that these were meant to be taught from an early age, was that when a human pulls a cart instead of the mule, the world goes crazy. When children punish their parents, the world goes crazy. When a woman assumes the visual presence of a man, the world goes crazy. Le Monde Renversé has its origins in medieval carnival culture, where institutions like government and religion were suspended and social roles were inverted, including gender roles. What made the coiffure à la Titus a problematic image was that it was not on carnival day; it penetrated everyday life. Ultimately, the coiffure à la Titus failed to establish itself as a style that could be separated from its highly charged connotations of gender dynamics. Continual compromises with ideals of femininity robbed it of its once shocking starkness, though criticism followed the Titus to the very end.

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!